The Life of Lee (3 page)

Authors: Lee Evans

By now, they would be very drunk and at the stage where local grievances began to surface. One particularly memorable New Year’s Eve, I was watching with interest as two neighbours begin to get more and more irritated with each other – nothing major, just the usual ‘You don’t keep your piece of the landing as tidy as everyone else’s’. At that moment, I caught sight of Doreen, another neighbour, a short, hunched, scruffy woman with small, beady eyes and a pointy nose. Doreen liked a drink, I think, and was already unsteady on her feet. She suddenly flung her arms in the air and announced: ‘Bollocks to this. I’m off to the toilet.’

Nobody took any notice, but just carried on arguing. After a minute or two, there was an almighty scream from the direction of the toilet. Everyone stopped what they were doing and listened, a look of concern on their faces.

‘Doreen?’ enquired Mum.

Everyone rushed out of the kitchen. I followed and found them all gathered around the toilet door. ‘Doreen? You all right, love?’

‘Mo, I am MOT aff might!’

‘Have you got a problem in there?’

‘Me teeff aff gom bown the bog.’

‘Let’s have a look.’

‘Well, how can you fee from vere? The frigging boor’s shut.’

‘Then open the door. Silly cow.’

Doreen opened the door with some embarrassment and stood in the entrance, swaying and hanging on to the handle to steady herself. Poor Doreen had lent over the toilet at the same time as she pulled the flush, and her

teeth had fallen into the bowl and been whooshed away. Looking at her face, I personally thought they’d jumped ship.

‘Quick!’ shouted Dad, taking charge. Everyone bundled down the stairs and out into what was now daylight, and over to the manhole cover that serviced the flats. Dad lifted the cover as everyone gathered round.

‘You lot,’ he ordered a couple of us kids. ‘Go and pull all the flushes and turn on all the taps.’ We raced off. Beginning at the top flat, we started turning as many taps and pulling as many flushes as we were able. We then ran back downstairs to the waiting crowd at the drain hole.

Doreen emerged from the flats and staggered over, swearing all the way. ‘Buddy peeth! They’re too loose anyway, ssshhhlipping all ober me gob.’ She arrived at the hole and squeezed through the crowd. Looking into the gaping maw, she moaned through her gums, ‘Sssstufff em, they’ll be in the Avon by mow.’

Everybody watched in nervous expectation as the water gushed from the pipe into the T-junction that took the waste and sewage away. ‘I think they might be halfway to Avonmouth by now, Dor …’

Doubt was seeping into the gathered crowd. ‘Put the lid back on,’ said Doreen, disconsolately. People began filing away dejectedly, back into the flats.

Dad picked up the lid and was about to drop it back into place. ‘Wait!’ he shouted. Everyone ran back to look down the hole. And there, poking out of the gushing outlet, were the smiling teeth – or were they in fact grimacing, having been apprehended trying to make good their escape? Either way, they were edging themselves slowly

out and about to fall into the T-junction. With no concern for health and safety – we had never heard of those words back then – Dad reached down and snatched them up.

Picking off the debris and wet toilet paper, he handed them to Doreen, who, without hesitating, popped them back into her mouth.

‘Cheers. Now where did I put me drink?’

And, with that, she staggered quite nonchalantly back through the crowd and into the flats, leaving everyone stunned.

That kind of incident was commonplace on the Lawrence Weston. We existed on not much at all. I suppose some people might have seen us as outlaws or even crossed the street to avoid us because of what we looked like. But they didn’t know anything about us – we did our best with what we had. We had no knowledge of any other way of existing. Life may have been tough, but we just got on with it.

And if we picked up a painting of Prince Charles along the way, so much the better!

3. My Family

That feeling of being excluded from the mainstream was drummed into me from birth by my dad, a man who gave the impression that he was constantly at odds with the world. In those days, his favourite gesture was to look up the sky, tut and say, in tones dripping with sarcasm, ‘Thank you very much … for nothing! Someone up there doesn’t like me very much!’

Nan, Granddad, Dad and his brother, John.

At times, he was not an easy person to have around. He was forever fuming about the hand fate had dealt us. He wrestled with the feeling that he would never be accepted and constantly railed against his lowly status. He felt that everyone else was having a fantastic time at a party to which he had not been invited.

The trouble with Dad was that because he was constantly expecting to be attacked, he was forever on his guard. Convinced he was always being persecuted, he carried around an almighty chip on his shoulder. He also lived with an overwhelming fear and loathing of authority. An ex-teddy boy, he would refuse to back down if he believed he was right.

But then, in the blink of an eye, he could be your best mate and a funny, loving father. He was hilarious at times. The problem for Wayne and me was knowing how to tread that tightrope. We could never tell which way Dad was going to turn.

When he wanted to, he could charm the birds off the trees – although there weren’t many birds, or trees for that matter, on the Lawrence Weston. When Wayne and I were small, Dad was still working on the docks. But he gradually started to pick up more paid work in the evenings, singing in pubs. Like the two generations before him, he had the Evans singing gene. When my granddad belted out ‘Land of My Fathers’, tears would fill his eyes. ‘Hear that,’ he would wail, ‘that’s proper music, that is.’

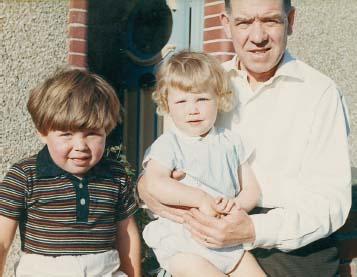

Wayne, me and Granddad.

My great-great auntie was also an amazing singer, who played on the Welsh and English music-hall circuits. Performing was in the Evans blood. Even though it took me an age to twig, I suppose it was really no surprise that I eventually ended up on stage.

Late at night, Dad would come back from his shows, burst into our bedroom clutching a handful of pound notes and regale us with tales of that night’s performance. It may only have been a show in a pub or a club, but to us it seemed like an impossibly glamorous universe that existed only on the telly. At those moments, the glittering world of showbiz briefly entered our grotty flat. We felt that, just temporarily, we were touched by magic. It seemed as if there might be a way out of the drabness of the estate. It felt like there was hope.

The glittering world of showbiz might have seemed light years away from our humble council flat but, strangely, it kept knocking on our front door. The two apparently irreconcilable worlds collided – one dark and desperate, the other seemingly shiny and out of reach for us mere mortals. It may have appeared impossibly

remote, but I suppose I was already getting a glimpse of the glitter.

I still vividly remember the first time I saw Dad perform. I must have been six or seven. Wayne and I stood clutching Mum’s hand at the back of a pub as he came on stage. Suddenly – kapow! – he started singing and we were mesmerized. We couldn’t believe how brilliant and how powerful he was onstage. He was like a force of nature, a second Tom Jones. He could blow a crowd away with the sheer potency of his performance. It was as if he was saying to the audience, ‘You’re going to have this and there’s nothing you can do about it. We’re going to blast the roof off!’

Dad appeared to be releasing all his pent-up anger. It hit you in the pit of the stomach with a rare energy. It was electrifying. To see all these people transfixed by Dad was an extraordinary experience and such a departure from the mundanity of our daily lives. His word was law at home, and his magnetic performance only added to the potent myth of his god-like domestic status.

Granddad, Dad and Nan in Rhyl, Wales.

But then, on other days, the mood in our flat could be decidedly dark. Often, reality would bite the morning after a show. There was never enough money and Dad would soon be worrying about bills again. His simmering sense of resentment often boiled over into the most fearful rages. He had a ferocious temper – and unfortunately, probably because of her background, so did Mum. When they went at it like cat and dog with helmets on, Wayne and I would cower in the corner. We wanted to be anywhere other than in the midst of that horrendous row.

When aroused, Dad’s temper would possess his whole

body. He was like the Incredible Hulk – although he turned red rather than green. It was like living with an angry traffic light. Then, just as quickly, the rage was gone, leaving him exhausted, wondering what had happened and apologizing, as if the fury had gripped someone else entirely. We lived in a state of constant fear about when he would next blow his top.

Dad’s rages only added to our sense of being outsiders. Because of his insecurities, he would drill us never to ask for anything. Whenever we met someone new, we were taught to say ‘please’, ‘thank you’ and – above all – ‘sorry’. We were never allowed to connect properly with anyone, and that made us feel cut off from the world. That’s why I kept myself to myself as a child, terrified of stepping out of line. I would play the fool, but only to mask my innate shyness. I lived in mortal terror of standing out from the crowd, in case I was doing something wrong. I was a textbook misfit. If there was an instruction booklet on how to be one, I could have written it.

Dad was never far from snapping. When he was at home in Bristol, he was unable to relax properly. He was always irritable, always fretting about where the next meal was coming from. His mind was constantly plagued by anxiety. He would sit in the chair bouncing his leg up and down, biting his nails, moaning or shouting at the telly. In his presence, you were constantly treading on eggshells.

Whenever I was out and about with him as a kid, I always felt things could flare up at any moment. His mood fluctuated wildly. Sometimes Wayne and I walked down the street with him having the time of our life. But it would only take one tiny incident for him to explode. He

had no blue touch paper – he was a spontaneously combusting rocket. He would never just let it lie. He was like a Jack Russell; once his teeth sank into you, they were never going to let go. That was the prevailing storm force in the house when we were kids – and it left us feeling bewildered and bedraggled.