The Life of Lee (20 page)

Authors: Lee Evans

Learning the drums!

Bill’s mum, an elderly, grey-haired lady, didn’t like what we played. She fumed that it was too loud and too aggressive. As soon as she left the room, Bill would turn to me and say, really aggressively, ‘It’s not aggressive! It’s gentle!’ On the word ‘gentle’, he would smash his fist into the pillow in his tiny bedroom upstairs at his council house. We’d been confined to play there, strumming frustratingly quietly and singing in that sort of fake throaty whisper you do when you imagine that you’re in front of a large, enthralled crowd. But one mistakenly played loud chord, and his mum’s angry grey head would once more be poking round the door: ‘Now I won’t tell you again, William!’

If we were rehearsing at my house, we were allowed to set up the drum kit in our garage and go bananas. Plus, Bill was permitted to plug his guitar in at low volume. Although we had to keep the noise down because of the neighbours, we were amped, and so felt like a proper band. We could only play for an hour, though, before someone would be banging their fist on our garage door for us to shut the noise up.

I would bash away on the drums, while Bill tried singing over the top. Every now and again, he would shout over to me, ‘It’s good, ain’t it, Lee?’ his eyes wide and wild-looking. I would respond by banging even harder and sort of growling back at him over the drums through a face full of spots.

We actually sounded like a major pile-up on the M3 between a lorry carrying cymbals and another transporting zoo animals, but we thought we sounded fantastic. We began to take ourselves seriously by trying to look

moody whenever we were out up the high street, combing our hair in various directions so it looked as though we’d just arrived on a motorbike. We’d hang around a lot smoking roll-ups and reflecting that the reason we had no gigs was because we were really a studio band – even though we’d never been in a studio.

So we mused that we could perhaps write our album in the garage. We just had to find two more people – hopefully with some instruments – and then we’d be a proper band. As far as we were concerned, we were going to be the next Beatles. Unfortunately, all we actually seemed destined to be was four Pete Bests, the bloke who dropped out before they made it big.

Bill had exactly the same ambitions for the band as I did. However, it was difficult to realize those as he could be a little unpredictable in nature. He might be perfectly gentle and amicable with you one minute, then the next he’d completely lose it. At band practice, he would suddenly slide into the corner and drift off into his own small world, tranced-out and fixated on his amp, which was turned up so loud it surely showed up on the Richter Scale in Brazil.

He’d gaze off into space like some absent-minded cabbage, strumming away on the strings of his guitar. He was cut off from everything around him like someone who had just been hit over the head with a large anvil, ungluing something in his head. He had the infuriating habit of constantly contradicting anything you said, just for the sake of being contrary and wanting an argument. He also had about as much patience as a great white shark on a case of Red Bull at feeding time and he loved to fight. Bill

was a small stout lad, as solid as a pit bull on steroids, with a cow’s-tail hairdo perched at the top of his forehead. He wore huge, thick glasses that magnified his mad, mischievous eyes, making them look like windows into the asylum without any bars.

What a guitarist Bill was! There wasn’t a chord he didn’t know. He was like Bert Weedon on amphetamines. During a number, his fingers would move continuously, rapidly reforming into all kinds of shapes, whipping across the frets in a blur, up and down the neck of his Gibson copy. When he really got going – watch out! – he was like a train with no leaves on the line and no brakes. But once he was on one, you didn’t dare stop him. That would be like waking up an unhinged man while he sleep-walked. If you interrupted his flow when he was at full tilt on those frets, he was likely to rip your face off and use it as a joke mask.

The Cave Club was a much-coveted local venue in Brentwood, the next town along from Billericay. The club was a magnet for any budding musician; it introduced lots of new bands from around the area. So it was important that we somehow got a gig there. When we eventually had the desired four members of our band, we called ourselves

THE ANONYMOUS FIVE

. Even though there were only four of us, it sounded good, and if anyone asked where the other guy was we always replied that he liked to stay anonymous. Either way, people just smirked at our terrible explanation.

So there was Bill and me, Alan, the rich kid with his own set of drums – a great asset because his parents didn’t mind us practising in the shed at the back of their

house – and a guy called Rob. He was a real hottie, heart-throb type who stood around wearing dark glasses indoors, with his legs astride a large set of bongos, striking the odd pose while rhythmically bashing animal skins. He was all virile and strapping. Women loved him, so of course I hated him. He was chosen not necessarily for his musical skills – mainly because he had none – but for his looks. He was a real magnet for the birds. Me and Bill’s somewhat crafty way of thinking was that Rob would churn the waters for us, and we could come and pick up the girls he didn’t want, like hungry seagulls behind a fishing boat. Well, at least, that was the idea. It didn’t work in practice – I remained resolutely girlfriend free!

As it was our very first gig, the booker at The Cave begrudgingly took a chance by letting us play there. He only shoe-horned us in after another band had cancelled at the last minute, catching us by surprise and allowing us no time at all to practise. We were lucky in a way. If the booker had known what we actually sounded like, he probably wouldn’t even have let us open our guitar cases, let alone open ‘Friday Night Is Band Night’ – which was held, coincidentally, on a Friday.

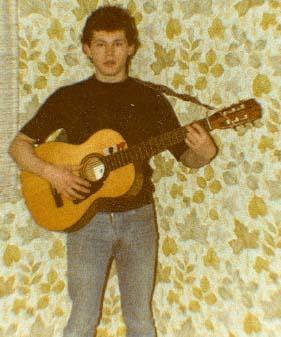

Me on guitar!

I reckon it must have been Bill’s relentless phone calls to the booker that somehow swayed it for us to play. Once Bill had the bloke at The Cave’s number, he was like a pike on the end of a fishing line – he wasn’t going to let go. He even called up impersonating an A&R man. I watched nervously, cringing as Bill got himself into character before making the all-important call to the club. Checking to make sure his mum had gone out, he kicked back on a chair next to the phone and sucked on a pencil so it might

sound like a cigar down the line. With slight menace in his voice, he told the booker that he was calling from EMI and was advising the club to ‘Quickly book us – them …’ Then, knowing he had messed up, he got all frustrated with himself and began rambling angrily down the phone. ‘I mean

them

… Shit! Look, book us or else, right … Balls … Sorry, I didn’t mean

us

… Oh, freakin’ hell!’

Struggling to keep control, Bill put his hand across the mouthpiece, looked over at me and wailed, ‘I think I’ve fucked up ’ere, Lee.’ Then he lifted his hand and shouted angrily, ‘Well, I ain’t Brian soddin’ Epstein.’ He proceeded to make his customary face, resembling an angry ape who had just been kicked in the bananas, calmed himself and started over.

Still in manager mode, he explained to the booker that there was a real buzz about these boys, and they would, funnily enough, be free this Friday. ‘Well,’ continued Bill, beginning to relish his new role as a music industry big shot, ‘that is after shooting their video and finishing a brief, unplugged open-tuning session with The Clash.’ He wasn’t technically lying with that remark as his mum wouldn’t let us plug in. ‘And then there’s a bit of a jamming thing to cut a new groove disk with The Pistols. Luckily for you, they’ll be kicking around on Friday. But a word to the wise: be careful. If the fan club find out, then stick a helmet on.’

Eventually, Bill wore the booker down. I think he got so frustrated with the constant calls that in the end he just gave in. But who cared? The Cave gave us a rare chance to play live. ‘I promise once you’ve seen us – er, them – play, you will never forget us – sorry, them.’ Bill put the phone

down and both of us jumped around his living room with excitement. Then slowly it dawned on us: we had never played live, never had everything up and running like you would if you were actually a band. The only live playing we had done was in rich Alan’s garden shed. Basically, we were no better than your average set of garden tools.

Bill would be proved right in what he said to that booker: the club wouldn’t forget us in hurry – but, unfortunately, for all the wrong reasons.

I am a dreamer, an optimist – always have been. Back then, I naively believed, like most kids do who have a band, that our group would be huge. I thought that with our superb musical skills and the tremendous songs written in Bill’s bedroom, it was only a matter of time before the phone would ring and I’d be speaking to a record producer who had somehow been driving past and heard us playing in Alan the drummer’s back shed. Forget the fact that this would have been quite impossible as the shed was way too far from any road. The whole idea was, in fact, ridiculous, but I imagined it happening anyway because I really believed that somehow or other my natural inclination was to step on a stage – I just didn’t know how or why right then.

However, my expectations of music-biz stardom did begin to fade somewhat during that fateful, all-important gig at The Cave when – out of nowhere – a giant brawl broke out all around us. It was fearsome; it swept the entire room like a wild fire of violence, ending up resembling one of those saloon free-for-alls you see in Westerns.

But, I hasten to say, it didn’t dampen my spirits one bit; no, it only momentarily made me fear for my life and shit

my new, tight Sta Prest trousers. As the fists flew, my main concern was to protect myself from the rain of flying glasses and beer cans by using my bass guitar as a sort of umbrella.

That’s when everyone, including Bill, seemed to just disappear. I looked around and realized I was on my own on the stage. All I could see were bodies, fists, bottles and chairs, all being thrown and landing here, there and everywhere. The whole room was heaving with violence and mayhem. My first reaction was to save my bass. I thought, ‘If anything happens to that, Dad will kill me.’ Then it occurred to me: ‘Wait a minute, I’m going to die anyhow. So who cares?’

After The Cave Catastrophe, as it came to be known, the next band practice was a much darker affair. There seemed an odd cloud of doubt hanging over rich Alan’s rehearsal shed. Things were different now, something was missing – well, Dave’s guitar, for one.

Maybe Dad was right when he warned me about a career in music. I could hear his voice resounding over and over in my head: ‘You can’t just become a musician.’ Now I wasn’t sure if I even wanted to be a musician.

My expectations had been well and truly dented. I knew ‘it’ wasn’t going to happen with that band – in fact, I didn’t even know what ‘it’ meant. They always say you learn something from your mistakes. Wait a minute. If that’s true, then how did ‘Chico Time’ get in the charts?

Well, I did learn something from my ill-fated spell with The Anonymous Five, something I hadn’t really known before: that when I was on the stage, something changed inside of me. I felt better than I did when I was off it. I

felt free. Even after all that violence started and everybody was running away, I stayed where I was. That was where I felt the safest, even as it was all going mad around me. I stood my ground because that’s where I believed I couldn’t get hurt. It’s ridiculous, I know, but it was the real world that I’d never quite been able to fathom, whereas I ‘got’ the stage. So I simply stayed where I was.

I also learned that I thought differently from everybody else in the group. My work ethic and mental discipline were not the same as theirs. I couldn’t even add up at school, but in the band I had an innate ability to separate each instrument, rearrange them, organize them in my head; I could tell each member to play something so that it sounded better when played along to a certain drum beat or bass line. I felt in charge.

Whether it was all the years of conditioning as a kid, sitting around theatres and clubs listening to music and watching performers, I wasn’t sure, but it certainly felt natural to me. That experience helped me find a role in this world that didn’t involve me feeling like an oddball, weird or excluded.