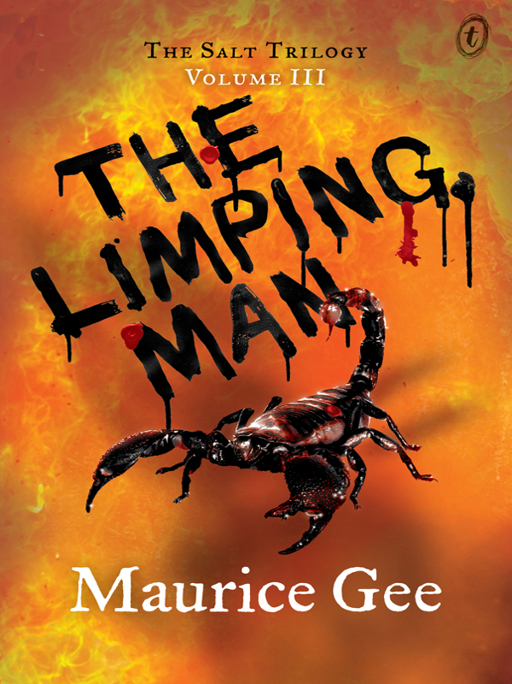

The Limping Man

Praise for

The Salt Trilogy

‘One of the most gripping pieces of fantasy writing I’ve read in a long while…fuses a vivid imaginative vision with profound ideas and a strong sense of history…Philip Pullman fans will find much to admire here.’

Weekend Australian

‘A genuinely exciting story line that never falters, even as Gee tests the very limits of his young protagonist.’

Sunday Age

‘A skilfully told story, taut and fast-moving, but with a rich texture of dark reality to it.’

Magpies

‘A compelling tale of anger and moral development that also powerfully explores the evils of colonialism and racism.’

Publishers Weekly

‘It is a marvellous moment when you read the first page of a new book and realise you are holding a classic of the future.’

Weekend Press

MAURICE GEE has written more than thirty books for adults and young adults, and has won several literary awards including the Deutz Medal for Fiction, the New Zealand Fiction Award and the New Zealand Children’s Book of the Year Award. Maurice Gee lives in Nelson, in New Zealand’s South Island.

The Text Publishing Company

Swann House 22 William Street Melbourne Victoria 3000

Australia

textpublishing.com.au

Copyright © Maurice Gee 2010

All rights reserved. Without limiting the rights under copyright above, no part of this publication shall be reproduced, stored in or introduced into

a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means (electronic,

mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise), without the prior

permission of both the copyright owner and the publisher of this book.

Published in Australia by The Text Publishing Company, 2010

Published in New Zealand by Puffin Books (NZ), 2010

Design by Mary Egan

Typeset by Pindar NZ

Map by Nick Keenleyside

Printed and bound in Australia by McPherson’s Printing Group

National Library of Australia

Cataloguing-in-Publication entry

Gee, Maurice, 1931-

The Limping Man / Maurice Gee.

ISBN: 9781921656293 (pbk.)

NZ823.2

Ebook ISBN: 9781921834554

T

HE

S

ALT

T

RILOGY

V

OLUME

III

Maurice Gee

TEXT PUBLISHING MELBOURNE AUSTRALIA

Contents

Hana ran through the broken streets of Blood Burrow. The smell of burning followed, sliding into her mouth as she gulped for air. It was as damp as toads. She would never wash herself free of it, and never stop hearing the women scream or wipe out the memory of the Limping Man.

‘Mam,’ she cried as she ran. Mam’s smiling face, her

shrewd eyes and careful hands, Mam bringing food and finding shelter and teaching her, always teaching, and always loving and always there – and Mam who had swallowed frogweed and was dead. Mam hadn’t burned. Unlike the others she had found time to chew and swallow. She hadn’t burned.

Hana had woken that morning to the cries of men in the streets, the screams of women and the wailing of children. Her mother came bursting into the shelter with the dawn sun streaming behind her, and wrenched the sack across the entrance. She turned and screamed, ‘Hana, run.’

‘Mam?’ Hana cried.

‘Into the crawl. Get as far away as you can. Don’t stop.’ With one hand she jerked Hana from her sleeping place, with the other clawed a fistful of weed from its pot on the shelf. She stuffed it in her mouth.

‘Mam,’ Hana shrieked.

Her mother forced her down, rolled her with her foot into the crawl. ‘Go. The Limping Man,’ she cried, with green froth dripping from her chin. She snatched more weed. There was terror in her eyes. ‘Hana, they’ll burn you.’

Hana went into the crawl, scraping her head, bruising her knees. ‘Mam, come with me,’ she screamed. But already her mother was rolling the stone across the entrance. Her mouth was foaming and the bite of the poison made her groan, but her eyes were as bright as embers and she said, in her own clear voice: ‘Hana, live. Don’t ever come back.’

Stone grated on stone. The hole closed. Hana heard the shouts of men in the room. She heard Mam scream and knew she had drawn her knife and run at them. Then she heard her fall and knew her mother was dead. The frogweed, the old women said, killed in twenty breaths.

Hana lay still, biting her hands to keep her terror and grief from breaking out. Men’s voices, panting, the clank of body armour, the hiss of swords sliding into scabbards, were less than a body-length away. A dog, if they had dogs, would sniff her out. But there was only the sound of tearing wood as the constables kicked down the sleeping bench in the corner, and the crack of pottery as they ground the mug and dish Hana had shared with her mother into the floor. Then the swish of the sack door pushed aside and the voice of a man in command: ‘This is her? The queen witch? You let her die?’

‘Captain, she ate the frogweed,’ a thick-tongued burrows voice replied.

‘He wanted her alive.’

‘Sir, she ran from us. She went down holes we could not follow.’

‘Where’s the girl? She had a daughter always at her side.’

‘No girl, sir. No one else.’

‘You were too slow. He’ll have you whipped. Bring this one. He’ll burn her anyway.’

Hana heard them drag her mother out of the shelter. She heard the clop of horse hooves and the creak and rumble of a cart and the thumping sound of Mam’s body thrown on the wooden tray. Women in the cart wailed and cried her name: ‘Stella, oh Stella, love.’ She recognised Morna’s voice and Deely’s voice and thought: He’s got them all. He had killed her mother. He had taken all her mother’s friends for burning.

Hana curled up tighter in the crawl. She pressed her arms and legs into herself, trying to shrink to nothing, to sink into the stone. She sobbed silently, and when the cart had rumbled away and the voices were gone, sobbed aloud. She did not know how long she lay on the cold floor, but realised, later, that she had slept, and she cried out with horror that she had allowed herself that escape, with her mother dead and her friends taken. She saw how Mam had saved her. There was room in the crawl for Mam, she could have come, but then there would have been no time to roll the stone across and hide the entrance. She had saved Hana, and died by frogweed rather than burn.

Hana lay curled up for a long time. She had no strength to move, although Mam’s words rang, and sometimes whispered, in her ears: ‘Hana, live. Get as far away as you can.’ She knew of no place to go. She wanted to stay near Mam even though she was dead.

At a time she judged to be noon she heard shuffling feet and hoarse whispers in the shelter. Scavengers had crept in and were sniffing and scraping in the wreckage. They would find Mam’s knife – she heard them find it – and some rags of bedding and a shirt and hood and sandals worn through on the soles. Little more. There was smashed wood that might be used on fires, and the iron pot sitting on ashes in the corner. No food in the pot. She heard their grunts of disappointment. Let them eat frogweed. The frogweed was still on the shelf. They went away and soon afterwards more whispering and creeping came, but this was a family, a man and woman and two children seeking a better home than the one they had. She heard the woman sigh with pleasure – this was a much better place. Hana wished the scavengers had left the pot and rags for her. A child whimpered and the woman said, ‘Hush,’ and at that sound Mam’s voice spoke in Hana’s ears: ‘Don’t ever come back.’

She lifted herself to her knees and her head struck the roof of the crawl.

‘Rats. Quiet,’ said the man.

‘They might come out. You can get one,’ whispered the woman. There was hunger in her voice.

They waited. Hana breathed softly, and after a while, as the noises of the family settled down, she crept away. She had only used the crawl once after Mam had shown her the way. Darkness had covered her like a sack, while the weight of stone pressed like hands on her back. She had felt she would never come out. Now she did not care. Tears fell on her hands as she crept.

Some way along she slept again and when she came out stars were blinking in the sky. She found water in the gutter of a fallen roof and drank. Dirty water. It did not matter. Nothing mattered now, even Mam’s order, get away. There was nowhere to get away to. Fires glowed in the ruins, with people moving round them, families perhaps – but even those with children would not welcome her. They did not have enough for themselves and kept the warmth of their fires guarded from strangers.

Hana turned back to the crawl, then turned away. Mam had used it and her smell was there. It smelled of Mam alive, and Mam was dead. Hana held her close in her mind, and let her go, and held her close again, but each time the grief of parting set harder, until it was a stone in her chest, it was a heart that refused to beat.

‘Mam, you were me and I was you.’ But that was only true back in the shelter, on the bench they had shared as a bed, in the rags they wrapped around each other at night, and now Mam was a heart that would not beat and Hana was . . . What am I? The only answer she could find was: I’m alone.

She wept again, not for herself but Mam. That way she held Mam again, not inside her chest as a second heart, but warm beside the fire at night with a rat stew bubbling in the pot.

‘Mam,’ she sobbed into the night. Then she ran, not knowing where. In the daytime she might have recognised caved-in streets and doorways that led nowhere, but in the night they were simply dips and hollows. Tiredness overwhelmed her at last and she crept under the ledge of a fallen wall and slept, dreaming broken dreams, until hunger woke her in the dawn. She held her stomach, moaning, weeping but, after several minutes of abandonment, knew she must help herself or die. Mam had taught her how to survive, that was her gift, and the rest was up to Hana.

After hours of searching she found her way deep into the bowels of a ruined building and found a black pool, and thrusting her arm into a hole at the edge, found a family of drain lobsters. Ignoring their bites, she pulled them out one by one and smashed their shells on a stone ledge and ate the flesh. Soon she would find flints to make a fire and cook what she caught, lobsters and eels and rats, but raw flesh would have to do now. She would have to find a knife to defend herself and a pot to boil water so she would not fall sick, and clothes to keep her warm and a place to sleep. But where, where? She remembered Mam’s words: Get away. Never come back. Did she mean out of the burrows? Hana knew no world outside the burrows.

She retraced her path into the daylight. Although she did not recognise buildings or streets, she knew from the smell of the air that she was in Blood Burrow. Her run in the night had taken her into the heart of the ruined city, away from the shelter she and Mam had shared in Bawdhouse Burrow. It was dangerous here, a man’s place – the Limping Man’s place. At the thought of him she was almost sick. He had killed her mother. He had taken all her mother’s friends and today he would come down from his palace on the hill, with his armoured constables, and ride in a litter, high on the shoulders of a squad of leather-clad bearers, and call the burrows men to People’s Square, and there he would burn them, the women known as witches – Morna and Deely and how many others? And burn Mam’s body as well. Hana wept again, then stopped herself. No more. No more crying, no more tears. They were a waste. They helped no one. She dried her cheeks with her hands. She must think and plan, as Mam had taught her. She must go back through Bawdhouse and down to Port and then perhaps – she shivered – she could find the place called Country and go there. In all her thirteen years Hana had seen the sea only once and had never seen Country.

She made her way carefully through the ruins. There were women with pots and buckets drawing water from a well at the meeting of two streets, and children climbing in rubble heaps, hunting for edible lichens or – the greatest prize – a nest of beetles and a clutch of beetle eggs. There were men too, going to their work in People’s Square. They would raise timber benches, ten flights high, with a throne at the centre where the Limping Man would sit, surrounded by his guests and guards and servants, to watch the burnings.