The Little Ice Age: How Climate Made History 1300-1850 (31 page)

Read The Little Ice Age: How Climate Made History 1300-1850 Online

Authors: Brian Fagan

The bread riots and harsh security efforts that tried to expel vagrants

from Paris and other centers heightened the anxiety. Everyone believed

the aristocrats would forge an alliance with brigands and wage war against

the poor. In fact, the alleged alliance was a rumor propagated by revolutionaries who saw an aristocratic plot at every turn. Bands of peasants

armed themselves throughout the country.

Hunger, hope, and fear drove the rural crisis of 1789. But what made

the crisis different from earlier ones were political expectations arising from an impending election of deputies, in which each peasant would

have an individual vote and a chance to state a grievance in a cahier. Many

were naive enough to believe that the writing of a cahier would produce an

immediate addressing of the complaint-the reduction of tithes, an easing

of taxation, and so on. When nothing happened, the peasants started refusing to pay taxes and feudal dues. After July 13, -there were widespread

disturbances in the countryside, directed especially at seignorial castles and

manor houses. The insurgents searched for grain stores and especially for

legal documents establishing feudal rights, which were promptly burned.

In some cases, lords were forced to sign declarations that they would not

reimpose them in the future. The disturbances were remarkably orderly

except when lords or their agents offered violence. Then there was bloodshed and burnings. Some bands were led by men who even bore orders

said (falsely) to have come from the king himself.

The trail of destruction and reports of widespread rural insurrection

soon reached Paris, where the National Assembly turned its immediate attention to feudal privilege and to the needs of the peasants. On August 4,

1789, deputies of the more liberal aristocracy and clergy surrendered their

feudal rights and fiscal immunities. In triumph, the Assembly claimed that

"the feudal regime had been utterly destroyed," a misleading statement, for

they merely surrendered some lasting remnants of serfdom, while other

privileges were only redeemable by purchase. Four years later, the insistence and militancy of the peasants led to the cancellation of all debts.

A prolonged drought now added to the chaos. Rivers dried up and watermills came to a standstill, resulting in a flour shortage and another surge

in food prices. By mid-September, the women of the markets were leading

the agitation that led to the famous march to Versailles on October 5. Two

columns of protesters marched in the rain to the palace to present their demands to Louis XVI. He promptly gave orders to reprovision the capital

and sanctioned the National Assembly's August decrees and the all-important Declaration of Rights of Man and Citizen, which was to form a partial basis for the new Constitution. The royal family was forced to accompany the crowd back to Paris and the ancien regime collapsed.

The Great Fear was, in the final analysis, the culmination of a subsistence crisis that had brewed for generations, of a chronic food dearth triggered by draconian land policies and sudden climatic shifts that pushed millions of French peasants across the fine line separating survival from

deprivation. The panic was followed by a violent reaction, when the

countryside turned against the aristocracy, unifying the peasants and

making them realize the full extent of their political power. There would

probably not have been a French Revolution if hate for outmoded feudal

institutions had not unified peasant and bourgeois in its attempted destruction. The events of 1789 stemmed in considerable, and inconspicuous, part from the farmer's vulnerability to cycles of wet and cold,

warmth and drought. As Sebastian Mercier wrote prophetically in 1770:

"The grain which feeds man has also been his executioner."24

This was succeeded, for nearly an hour, by a tremulous motion

of the earth, distinctly indicated by the tremor of large window frames; another comparatively violent explosion occurred

late in the afternoon, but the fall of dust was barely perceptible. The atmosphere appeared to be loaded with a thick

vapour: the Sun was rarely visible, and only at short intervals

appearing very obscurely behind a semitransparent substance.

A British resident ofSurakarta, eastern Java, on the Mount

Tambora eruption, April 11, 1815

n April 11, 1815, the island of Sumbawa in eastern Java sweltered

n April 11, 1815, the island of Sumbawa in eastern Java sweltered

under a languid tropical evening. Suddenly, a series of shocks, like cannon fire, shattered the torpid sunset and frightened the inhabitants, still

jittery about gunfire. Napoleon's representative to the Dutch East Indies

had only recently been driven from the islands and the British were administering the region. The garrison at Jogjakarta sent out a detachment

of troops to check on nearby military posts. As the sun set, the fusillade

seemed to grow louder. By chance, the British government vessel Benares

was in port at Makasser in the southern Celebes. She set sail with a force

of troops to search the islands to the south and flush out any pirates.

Finding none, the Benares returned to port after three days. Five days

later, on April 19, the explosions resumed, this time so intense that they

shook both houses and ships. The captain of the Benares again sailed southward to investigate, under a sky so dark with ash he could barely see

the moon. Complete darkness mantled the region, cinders and ash rained

down for days on villages and towns. Mount Tambora, at the northern

tip of Sumbawa, had erupted with catastrophic violence.

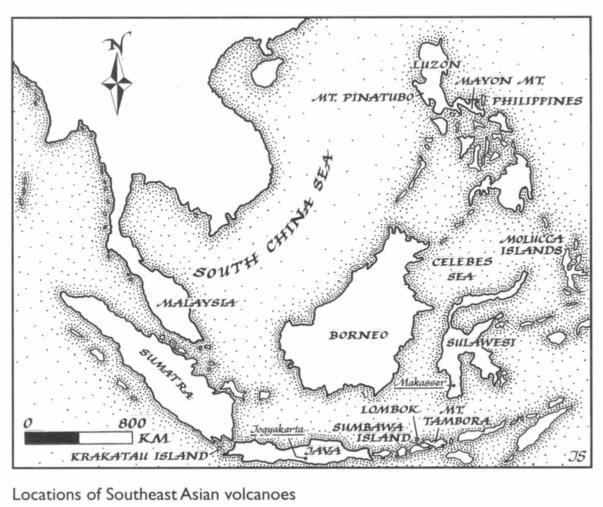

After three months of violent convulsions, Mount Tambora was 1,300

meters lower. Its summit had vanished in a cloud of lava and fine ash that

rose high into the atmosphere. Volcanic debris smothered the British resident's house sixty-five kilometers away and darkened the sky over a radius

of five hundred kilometers. The British lieutenant governor of Java, Sir

Thomas Stamford Raffles, wrote: "The area over which tremulous noises

and other volcanic effects extended was one thousand English miles

[1,600 kilometers] in circumference, including the whole of the Molucca

Islands, Java, a considerable portion of Celebes, Sumatra, and Borneo.

... Violent whirlwinds carried men, horses, cattle, and whatever came

within their influence, into the air."' At least 12,000 people on Sumbawa

died in the explosion, and another 44,000 from famine caused by falling

ashes on the neighboring island of Lombok. Floating trees covered the ocean for kilometers. Fierce lava flows surged downslope into the Pacific

and covered thousands of hectares of cultivated land. Floating cinders

clogged the Pacific to a depth of six meters over an area of several square

kilometers.

Volcanologists have fixed the dates of more than 5,560 eruptions since

the last Ice Age. Mount Tambora is among the most powerful of them all,

greater even than the Santorini eruption of 1450 B.C., which may have

given rise to the legend of Atlantis. The ash discharge was one hundred

times that of Mount Saint Helens in Washington State in 1980 and exceeded Krakatau in 1883. Krakatau, the first major eruption to be studied

at all systematically, is known to have reduced direct sunlight over much of

the world by 15 to 20 percent. The much larger Tambora event, coming

during a decade of remarkable volcanic activity, had even more drastic effects at a time when global temperatures were already lower than today.

At least three major volcanic eruptions occurred between 1812 and

1817: Soufriere on Saint Vincent in the Caribbean erupted in 1812,

Mayon in the Philippines in 1814 and Tambora a year later. This extraordinary volcanic activity produced dense volcanic dust trails in the stratosphere. The Krakatau event provides scientists with a baseline index for measuring the extent of volcanic dust veils. If 1883 is given an index of 1,000,

1811 to 1818 is roughly 4,400. Another set of powerful eruptions between

1835 and 1841 produced an index of 4,200 and further colder weather.

Dense volcanic dust at high altitudes decreases the absorption of incoming solar radiation by reducing the transparency of the atmosphere,

which leads to lower surface temperatures. The effects can be gauged by

worldwide measurements taken after the Krakatau eruption of 1883,

when the monthly average of solar radiation fell as much as 20-22 percent below the mean value for 1883-1938. While an increase in scattered

light and heat (diffuse radiation) compensates for some of the depletion,

a fluctuation of only 1 percent in the solar energy absorbed by the earth

can alter surface temperatures by as much as 1 °C. In a marginal farming

area like northern Scandinavia, this difference can be critical.

A decrease in solar radiation leads to a weakening of zonal circulation

in northern latitudes and pushes the prevailing westerly depression tracks

southward toward the equator. The subpolar low moves southward.

Cooler and duller spring weather arrives in northern temperate latitudes, bringing more storms than usual. Sustained volcanic activity can have a

powerful effect. The great eruptions of 1812 to 1815 helped move the

subpolar low of midsummer down to 60.7° north, a full six degrees farther south than it was in the Julys between 1925 and 1934.

The years 1805 to 1820 were for many Europeans the coldest of the Little Ice Age. White Christmases were commonplace after 1812. The novelist Charles Dickens, born in that year, grew up during the coldest

decade England has seen since the 1690s, and his short stories and A

Christmas Carol seem to owe much to his impressionable years. Volcanoes

were the partial culprit. The Tambora ash, lingering in the atmosphere

over much of the world for up to two years, produced unusual weather. A

two-day blizzard in Hungary during late January 1816 produced brown

and flesh-colored snow. The inhabitants of Taranto, in southern Italy,

were terrified by red and yellow snowflakes in a place where even normal

snow was a rarity. Brown, bluish, and red snow fell in Maryland in April

and May. Everywhere, the dust hung in a dry fog. Wrote an English vicar:

"During the entire season the sun rose each morning as though in a cloud

of smoke, red and rayless, shedding little light or warmth and setting at

night behind a thick cloud of vapor, leaving hardly a trace of its having

passed over the face of the earth."2