The Log from the Sea of Cortez (4 page)

Read The Log from the Sea of Cortez Online

Authors: John Steinbeck,Richard Astro

The clearest picture of the differences between Steinbeck and Ricketts regarding the proper course of human action for those who can “break through” can be drawn from a short film script Steinbeck wrote during the composition of

Sea of Cortez,

and an essay Ricketts wrote in response. Steinbeck returned to Mexico for a short time during the summer of 1940 with filmmaker Herb Klein to make a study of disease in an isolated village; this study was made into a well-received documentary entitled

The Forgotten Village.

The script focuses on the initiative of a young boy, Juan Diego, who is outraged because a deadly microbial virus, which has polluted the village’s water supply and has killed his brother and made his sister seriously ill, is being treated by witch doctors when real medical help is nearby. Juan Diego leaves the village to find the doctors of the Rural Health Service, who return with him to cure the problem. Noting that “changes in people are never quick,” Steinbeck prophesies that, because of the Juan Diegos of Mexico, “the change will come, is coming; the long climb out of darkness. Already the people are learning, changing their lives, working, living in new ways.”

Sea of Cortez,

and an essay Ricketts wrote in response. Steinbeck returned to Mexico for a short time during the summer of 1940 with filmmaker Herb Klein to make a study of disease in an isolated village; this study was made into a well-received documentary entitled

The Forgotten Village.

The script focuses on the initiative of a young boy, Juan Diego, who is outraged because a deadly microbial virus, which has polluted the village’s water supply and has killed his brother and made his sister seriously ill, is being treated by witch doctors when real medical help is nearby. Juan Diego leaves the village to find the doctors of the Rural Health Service, who return with him to cure the problem. Noting that “changes in people are never quick,” Steinbeck prophesies that, because of the Juan Diegos of Mexico, “the change will come, is coming; the long climb out of darkness. Already the people are learning, changing their lives, working, living in new ways.”

After reading Steinbeck’s text, Ricketts wrote an essay he called his “Thesis and Materials for a Script on Mexico”—actually an antiscript to Steinbeck’s. In it, Ricketts noted that “the chief character in John’s script is the Indian boy who becomes so imbued with the spirit of modern medical progress that he leaves the traditional way of his people to associate himself with the new thing.”

The working out of a script for the “other side” might correspondingly be achieved through the figure of some wise and mellow old man, who has long ago developed beyond the expediencies of economic drives and power drives, and to whom for guidance in adolescent troubles some grandchild comes.... A wise old man, present during the time of building a high speed road through a primitive community, appropriately might point out the evils of the encroaching mechanistic civilization to a young person.

In his best fiction, Steinbeck worked out the conflict between primitivism and progress, between his own view of the world and that of Ricketts—both of which were based, of course, on a scientific view of life organized around the concept of wholeness which is as spiritual as it is biological. And the Ed Ricketts characters in Steinbeck’s fiction (they are several and are usually named “Doc”) are those who are somehow cut off. They see and understand, but they cannot act on the basis of that understanding for the betterment of the species. Doc Burton in

In Dubious Battle sees

and understands the plight of the striking apple pickers in the Tor-gas Valley, but he wanders off into the night, frustrated by his inability to act on their behalf. He is “reincarnated” as Jim Casy in

The Grapes of Wrath,

who returns as Christ from the wilderness, and, seeing life whole, realizing that “all that lives is holy,” gives his life to aid the dispossessed and disinherited. And there is Doc in

Cannery Row,

who wants only to “savor the hot taste of life,” even as the Row itself (which for Doc and his friends is “a poem, a stink, a grating noise, a quality of light, a tone, a habit, a nostalgia, a dream”) is really an island surrounded by an encroaching society which will ultimately destroy it. Little wonder the book is dedicated “to Ed Ricketts, who knows why or should.” And there is its sequel,

Sweet Thursday,

where the Ricketts character seems even more isolated in a book which is less sweet than bittersweet. And finally there is that strange play-novelette,

Burning Bright,

in which the Ricketts character (named Friend Ed) teaches the Steinbeck character (Joe Saul) how to see and understand things whole and then how to receive (a trait which, in “About Ed Ricketts,” Steinbeck identified as among Ricketts’s greatest talents).

In Dubious Battle sees

and understands the plight of the striking apple pickers in the Tor-gas Valley, but he wanders off into the night, frustrated by his inability to act on their behalf. He is “reincarnated” as Jim Casy in

The Grapes of Wrath,

who returns as Christ from the wilderness, and, seeing life whole, realizing that “all that lives is holy,” gives his life to aid the dispossessed and disinherited. And there is Doc in

Cannery Row,

who wants only to “savor the hot taste of life,” even as the Row itself (which for Doc and his friends is “a poem, a stink, a grating noise, a quality of light, a tone, a habit, a nostalgia, a dream”) is really an island surrounded by an encroaching society which will ultimately destroy it. Little wonder the book is dedicated “to Ed Ricketts, who knows why or should.” And there is its sequel,

Sweet Thursday,

where the Ricketts character seems even more isolated in a book which is less sweet than bittersweet. And finally there is that strange play-novelette,

Burning Bright,

in which the Ricketts character (named Friend Ed) teaches the Steinbeck character (Joe Saul) how to see and understand things whole and then how to receive (a trait which, in “About Ed Ricketts,” Steinbeck identified as among Ricketts’s greatest talents).

In the Log, Steinbeck writes a passage which could easily have been taken from the work of William Emerson Ritter (it appears nowhere in Ricketts’s notes on the trip), in which he reflects that “there are colonies of pelagic tunicates which have a shape like the finger of a glove.” Steinbeck remarks that “each member of the colony is an individual, but the colony is another individual animal, not at all like the sum of its individuals.” And, says Steinbeck, “I am much more than the sum of my cells and, for all I know, they are much more than the division of me.” There is “no quietism in such acceptance,” notes the novelist, “but rather the basis for a far deeper understanding of us and our world.” This is Ritter’s organismal conception, which Steinbeck learned at Hopkins and discussed for so many years with Ricketts. At the core of the argument is the premise that, since given properties of parts are determined by or explained in terms of the whole, the whole is directive, is capable of directing the parts. In other words, the whole acts as a causal unit—on its own parts. As stated above, W. C. Allee’s doctrine of social cooperation among animals was unconscious and involuntary; the process of cooperation was automatic. What appealed to Allee and to Ricketts was that this concept offered them an approach to reality that enabled them to break through to a view of the total picture. But seeing and understanding the whole picture, what Jim Casy calls “the whole shebang,” and acting on the basis of that understanding, are two different things.

Sea of Cortez

enables us to see Ricketts and Steinbeck searching for and finding whole pictures. Steinbeck’s novels and Ricketts’s more recently published essays and articles provide us with a deeper understanding of the similarities and differences in their respective worldviews.

Sea of Cortez

enables us to see Ricketts and Steinbeck searching for and finding whole pictures. Steinbeck’s novels and Ricketts’s more recently published essays and articles provide us with a deeper understanding of the similarities and differences in their respective worldviews.

We read

Sea of Cortez

for its own sake as a first-rate work of travel literature. We read it also to understand the range and depth of Ricketts’s impact on Steinbeck’s fiction. And this permits us to see Steinbeck’s fictional accomplishments in a new and fresh light. In so doing, we see not just the absurdity of arguments raised by those who attacked this or that Steinbeck novel on the basis of his alleged belief in any particular political ideology. We see also that his thinking is not worn and obsolete, but is as current as the modern environmental movement, which it predates and with which it has so much in common. If we read and consider

Sea of Cortez

in all its complexity, we see John Steinbeck fusing science and philosophy, art and ethics by combining the compelling if complex metaphysics of Ed Ricketts with his own commitment to social action by a species for whom he never gave up hope, and whom he believed could and would triumph over the tragic miracle of its own consciousness.

Sea of Cortez

for its own sake as a first-rate work of travel literature. We read it also to understand the range and depth of Ricketts’s impact on Steinbeck’s fiction. And this permits us to see Steinbeck’s fictional accomplishments in a new and fresh light. In so doing, we see not just the absurdity of arguments raised by those who attacked this or that Steinbeck novel on the basis of his alleged belief in any particular political ideology. We see also that his thinking is not worn and obsolete, but is as current as the modern environmental movement, which it predates and with which it has so much in common. If we read and consider

Sea of Cortez

in all its complexity, we see John Steinbeck fusing science and philosophy, art and ethics by combining the compelling if complex metaphysics of Ed Ricketts with his own commitment to social action by a species for whom he never gave up hope, and whom he believed could and would triumph over the tragic miracle of its own consciousness.

SUGGESTIONS FOR FURTHER READING

Allee, W. C.

Animal Aggregations.

Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1931.

Animal Aggregations.

Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1931.

Astro, Richard.

John Steinbeck and Edward F. Ricketts: The Shaping of a

Novelist. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 1973.

John Steinbeck and Edward F. Ricketts: The Shaping of a

Novelist. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 1973.

——.

Edward F. Ricketts.

Western Writers Series. Boise, Ida.: Boise State University Press, 1976.

Edward F. Ricketts.

Western Writers Series. Boise, Ida.: Boise State University Press, 1976.

Benson, Jackson J.

The True Adventures of John Steinbeck.

New York: Viking Press, 1984.

The True Adventures of John Steinbeck.

New York: Viking Press, 1984.

Boodin, John Elof.

Cosmic Evolution.

New York: Macmillan Press, 1925. Fadiman, Clifton. “Of Crabs and Men,”

New Yorker,

December 6, 1941, 107.

Cosmic Evolution.

New York: Macmillan Press, 1925. Fadiman, Clifton. “Of Crabs and Men,”

New Yorker,

December 6, 1941, 107.

Fontenrose, Joseph.

John Steinbeck: An Introduction and Interpretation.

New York: Barnes and Noble, 1964.

John Steinbeck: An Introduction and Interpretation.

New York: Barnes and Noble, 1964.

Hedgpeth, Joel W. “Philosophy on Cannery Row.” In

Steinbeck: The Man and His

Work. Edited by Richard Astro and Tetsumaro Hayashi. Corvallis: Oregon State University Press, 1971.

Steinbeck: The Man and His

Work. Edited by Richard Astro and Tetsumaro Hayashi. Corvallis: Oregon State University Press, 1971.

Knox, Maxine, and Mary Rodriguez.

Steinbeck’s Street: Cannery Row.

San Rafael, Calif.: Presidio Press, 1980.

Steinbeck’s Street: Cannery Row.

San Rafael, Calif.: Presidio Press, 1980.

Lisca, Peter.

The Wide World of John Steinbeck.

New Brunswick, N.J.: Rutgers University Press, 1958.

The Wide World of John Steinbeck.

New Brunswick, N.J.: Rutgers University Press, 1958.

Lyman, John. “Of and About the Sea,” American Neptune, April 1942, 183.

Mangelsdorf, Tom.

A History of Steinbeck’s Cannery Row.

Santa Cruz, Calif.: Western Tanager Press, 1986.

A History of Steinbeck’s Cannery Row.

Santa Cruz, Calif.: Western Tanager Press, 1986.

Person, Richard.

History of Monterey.

Monterey, Calif.: City of Monterey, 1972.

History of Monterey.

Monterey, Calif.: City of Monterey, 1972.

Ricketts, Edward F., and Jack Calvin.

Between Pacific Tides.

3d ed. Foreword by John Steinbeck. Stanford: Stanford University Press, 1952.

Between Pacific Tides.

3d ed. Foreword by John Steinbeck. Stanford: Stanford University Press, 1952.

——.

The Outer Shores.

2 vols. Edited by Joel W. Hedgpeth. Eureka, Calif.: Mad River Press, 1978.

The Outer Shores.

2 vols. Edited by Joel W. Hedgpeth. Eureka, Calif.: Mad River Press, 1978.

——. “The Philosophy of Breaking Through.” Unpublished MS, 1933.

——. “A Spiritual Morphology of Poetry.” Unpublished MS, 1933.

——. “Thesis and Materials for a Script on Mexico.” Unpublished MS, 1940.

Ritter, William Emerson.

The Unity of the Organism, or the Organismal Conception.

2 vols. Boston: Gorham Press, 1919.

The Unity of the Organism, or the Organismal Conception.

2 vols. Boston: Gorham Press, 1919.

——and Edna W. Bailey.

The Organismal Conception: Its Place in Science and Its Bearing on Philosophy.

Berkeley: University of California Publications in Zoology, 1931.

The Organismal Conception: Its Place in Science and Its Bearing on Philosophy.

Berkeley: University of California Publications in Zoology, 1931.

Steinbeck, Elaine, and Robert Walsten, eds.

Steinbeck: A Life in Letters.

New York: Viking Press, 1975.

Steinbeck: A Life in Letters.

New York: Viking Press, 1975.

Steinbeck, John.

Cannery Row.

New York: Viking Press, 1945.

Cannery Row.

New York: Viking Press, 1945.

——.

The Forgotten Village.

New York. Viking Press, 1941.

The Forgotten Village.

New York. Viking Press, 1941.

——.

The Grapes of Wrath.

New York: Viking Press, 1939.

The Grapes of Wrath.

New York: Viking Press, 1939.

A NOTE ON THE TEXT

The history of the publication of

Sea of Cortez

is interesting and chiefly involves the issue of joint authorship. Before the book was first published by Viking in December 1941, Steinbeck’s editor, Pascal Covici, suggested that the title page read as follows:

Sea of Cortez

is interesting and chiefly involves the issue of joint authorship. Before the book was first published by Viking in December 1941, Steinbeck’s editor, Pascal Covici, suggested that the title page read as follows:

The Sea of CortezBy John Steinbeck

With a scientific appendix comprising materials for a source-book

on the marine animals of the Panamic Faunal Province

By Edward F. Ricketts

Steinbeck objected vigorously, telling Covici that “this book is the product of the work and thinking of both of us and the setting down of the words is of no importance.... I not only disapprove of your plan—but forbid it.”

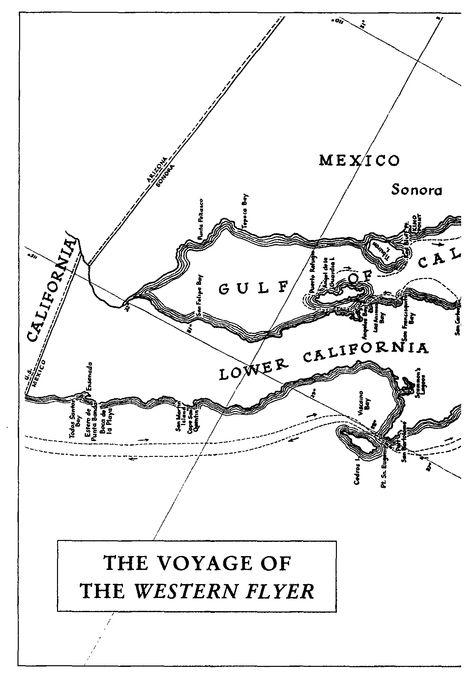

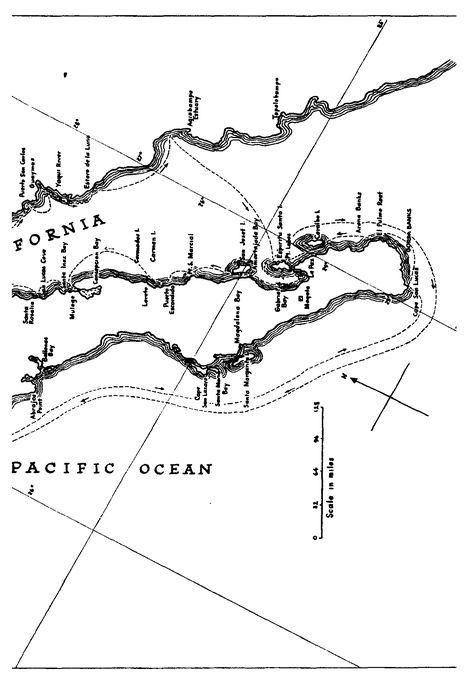

The book was originally published as

Sea of Cortez: A Leisurely Journal of Travel and Research

by John Steinbeck and Edward F. Ricketts, with copyright in both authors’ names. In 1951, the narrative portion of the book was published separately by Viking as

The Log from the Sea of Cortez,

with Steinbeck’s preface “About Ed Ricketts.” This Penguin Twentieth-Century Classics edition is based on the text of the 1951 publication; Steinbeck’s “About Ed Ricketts” has been moved to the back matter as an appendix to the main text.

Sea of Cortez: A Leisurely Journal of Travel and Research

by John Steinbeck and Edward F. Ricketts, with copyright in both authors’ names. In 1951, the narrative portion of the book was published separately by Viking as

The Log from the Sea of Cortez,

with Steinbeck’s preface “About Ed Ricketts.” This Penguin Twentieth-Century Classics edition is based on the text of the 1951 publication; Steinbeck’s “About Ed Ricketts” has been moved to the back matter as an appendix to the main text.

INTRODUCTION

The design of a book is the pattern of a reality controlled and shaped by the mind of the writer. This is completely understood about poetry or fiction, but it is too seldom realized about books of fact. And yet the impulse which drives a man to poetry will send another man into the tide pools and force him to try to report what he finds there. Why is an expedition to Tibet undertaken, or a sea bottom dredged? Why do men, sitting at the microscope, examine the calcareous plates of a sea-cucumber, and, finding a new arrangement and number, feel an exaltation and give the new species a name, and write about it possessively? It would be good to know the impulse truly, not to be confused by the “services to science” platitudes or the other little mazes into which we entice our minds so that they will not know what we are doing.

Other books

The Killing Club by Paul Finch

Tameable (Warrior Masters) by Kingsley, Arabella

Brain Buys by Dean Buonomano

Gamed (A Standalone Romance Novel) (Bad Boy Romance) by Adams, Claire

Remembering Satan by Lawrence Wright

Birdcage Walk by Kate Riordan

Vampires Never Cry Wolf by Sara Humphreys

Sun Signs by Shelley Hrdlitschka