The Long Shadow of Small Ghosts (4 page)

Read The Long Shadow of Small Ghosts Online

Authors: Laura Tillman

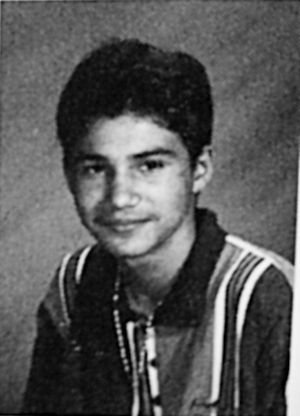

John Allen Rubio

(Photo courtesy of Louie Vera)

CHAPTER 4

Letters from the Edge

I loved to see the stars. Makes me think alot of the amazing univers we live in.

âJOHN ALLEN RUBIO

A

few months after I started writing to John, he sent me a letter with a list of addresses I'd requested. They were the intersections of his childhood, the places his family lived as he was growing up. I set out on a drive around Brownsville, looking for the landscape of those early years.

Most of the locations were vague. On this street, near this school. Around this corner. I'd idle in my car and look around. On one street I'd find a white house with a collection of two dozen potted plants in the yardâa small but cheerful little home with a clean paint job and a sign,

SE VENDE ÃRBOLITOS DE MANGO, NARANJA

, “we sell little mango and orange trees.” Then the list would lead to a run-down cream-colored apartment building with sickly green trim on a stark lot.

John could only recall leaving Brownsville on a handful of occasions. Sometimes he walked across the bridge to Matamoros, though he said this didn't really count, since everyone in Brownsville did the same. He took a school trip to San Antonio, where he ate pizza and

saw the restaurants and margarita-sipping tourists flanking the city's famed River Walk. “Everything was so big and amazing to me compaired to Brownsville.” Once, he traveled to Arkansas to apply for a job cleaning chickens at a Tyson factory, but wrote that he failed the drug test even though he hadn't smoked marijuana in over a month. Mainly, he “stuck to my home town which I loved very much.” John got to know a wide range of neighborhoods in Brownsville due to his parents' constant fights and financial instability. His family was often forced to go looking for a cheaper place to live, leaving wherever might have started to become home. John altered many details slightly as he recounted themâfrom statement to statement and letter to letter. I didn't always notice these variations in the moment, but taken together, they sometimes made it hard to pin down the “correct” version of events. What I have is the product of what John told me, the court record, and the results of my own inquiries.

John Allen Rubio was born on August 12, 1980, just after Hurricane Allen. His mother, Hilda, gave birth at Valley Regional Medical Center two days after Allen made landfall in Brownsville, a Category 5 storm that had simmered down to a Category 3 by the time it hit Texas. Allen knocked out power along the South Texas coast for several days, destroyed half of the region's cotton and citrus crops, and left residents without drinking water.

Hilda was in her early twenties when she gave birth to John and already had another son, Manuel, with a different man. Soon, two more brothers, Rodrigo and Jose Luis, would join the bunch. Hilda came from a large family herselfâshe was one of twelve children, six boys and six girls. Her own mother, Felicitas, would have forty-one grandchildren by the time she died.

John lived in several different neighborhoods spread across Brownsville, such as Cameron Park, a

colonia

that, while technically within the city limits, isn't part of Brownsville proper. For a time he lived at his grandparents' house in Barrio Buena Vida. He also lived in Southmost, a neighborhood close to the outer limits of Brownsville and the Rio Grande. There, the orange groves, cornfields, and nature sanctuary shared space along the river's snaking path. Turning down one street in this neighborhood led to a pocket of houses and parks. Turning down another, the levee appeared, where green Border Patrol trucks kicked up dust along the edge of the United States.

John's second letter described his time growing up in Brownsville, his “poor, disfuntional family,” and the beatings his mother frequently endured.

It was six of us living in the same house. My mom, my dad, my older half brother, myself, and two younger brothers. All us kids slept in the same bed most of the time except when we were kids and our parents bought us two bunk beds, one for each of us. We all slept in the same room always because we would get small places to live.

As a child I imagened myself living in a house built just for me. My perfect wife and perfect kids. I always wanted to be in the milatery so I thought this dream would come through some day and even promissed my mother that some day I would make her a house right next to my own so I can have her close to me forever. Growing up I loved both my parents but I was closer to my mom because she showed interesse in the things I did and liked. At least that was the way things were until she started doing crack cocain and changed alot.

I wanted to stay in Brownsville but buy a peace of land undeveloped where there is not much people or houses so it could be quiet. Enjoy the trees, animals that run around grassy places and the stars. I loved to see the stars. Makes me think alot of the amazing univers we live in.

Hilda testified that John's father beat her so badly, sometimes she couldn't open her eyes, and her older brother Juan said that both John and Hilda were beaten. “He used to just throw him all over the place, like if nothing mattered.” Juan told defense attorney Nat Perez Jr. that he wished he had reported the abuse to police, but didn't because “we were going to take care of it ourselves.” Hilda said John's father merely spanked him, but said that he did start giving John alcohol as early as age five, when he would feed the kindergartener beer.

“My father was very abusive, psysically, emotionally and mentally,” John wrote. “He seemed to struggle with expressing and/or excepting love.”

The mitigation phase, during which his attorneys tried to show how difficult John's life had been and give the jury a reason to spare him the death penalty, put his family in a harsh light. As John was sentenced during the second trial, neither Hilda nor his brothers came to support him.

I drove by one home near Porter High School, where John graduated in 1999, when he was almost nineteen. He remembered an exact address. The house was painted blue, with white bars over the windows and the door, and was surrounded by a large green lot. It didn't have the claustrophobic feeling of the apartment that would be John's final home before prison. Here the boys could have

played together, kicking a soccer ball through the grass, not unlike the children a mile away, in backyards abutting resacas. They might have watched some of John's favorite moviesâ

The Wizard of Oz

,

Grease

,

The Sound of Music

, and

Mary Poppins

. John remembered playing video games as a kid, one of his favorite activities. Sometimes, he played a cowboy game his father found at a flea market. He also liked catching tarantulas.

In one of his letters, John described his rivalry with his brother Jose Luis:

I was very wild, climing trees, running around, playing all kinds of crazy games and my little brothers would follow me around because I would do fun stuff. Rodrigo was more garded, to himself but let go when we were playing. He took things seriously. Jose Luis as like my arc-enemy, or so he thought I was his. He would always be looking to get me angry with him. He would lye in wait for me, hit me and then run to our parents yelling at the top of his head “Juan [John in Spanish] wants to hit me for no reason.” Really, for no reason!!! He was such a big lier an acter that my parents always believed him and it did not help that he was the baby of the house.

During the second trial, defense attorney Perez confronted Hilda with prior testimony that she had used crack cocaine while pregnant with John, but Hilda was adamant that she had not. She did admit to drinking a six-pack of beer a day all nine months, despite having been told that she shouldn't drink while pregnant. Her brother Juan testified that he saw Hilda huff paint during the pregnancy.

Dr. Jolie S. Brams, a psychologist who testified at the second trial,

said John likely had a thought disorder as early as preschool, and his ability to distinguish between reality and fantasy was impaired. Dr. Brams found John's parents to have had a “toxic” influence, “whose negativity and their behavior and their dysfunction in their daily lives hampered John Rubio's ability to be a normal healthy individual.”

John struggled with language as a child. Dr. Brams said he was unable to speak English fluently and “would talk to things that weren't there. But even when he spoke to his family members, he kind of did it in his own gibberish, as if he were living in his own world.” His motor skills were also delayedâhe never crawled and walked late. He had night terrors and believed in witchcraft. These, Dr. Brams said, were early “seeds of psychosis.” Dr. Brams concluded that John's difficult upbringing exacerbated his developmental problems.

But young John loved Hilda and clung to her, and his recollections in letters were of a mother in whom he could confide, who cared about his problems. He loved her more than anyone else and described her as a “best friend, a father and a mother, a counselor.” His uncle Juan described her as a good mother who loved her children and worked hard to support them for many years, until “the picture turned around.”

“You know, it's like when you look in the mirror and you see yourself, all of the sudden you just grab the image that's inside and bring it out, and that's the opposite side of you? That's what happened to her.”

An ex-boyfriend of Hilda's, who met her while she was working as a nursing assistant in the nineties, said Hilda quit her job after several steady years, telling him that “she was tired.” It seems that after this point, her substance abuse problem worsened.

When I asked John for good memories of his childhood, he told

me this story twice: His special-education class was putting on a performance, and the children were to pretend they were playing paper instruments while music swelled in the background from the stereo.

I needed white gloves, white button shirt, and black slacks. My father thought it was stupid but my mother thought it would be good for me to gain confidence so she bought me what I needed and because my dad didn't want to drive us to school, my mother and I walked the 2 miles or so to the school.

John was handed a cardboard saxophone, he recalled, and pretended it was real as the tape played behind them.

I was full of childish joy and loved the fact my mother didn't just get the things I needed but came with me all the way to school. My dad really did think it was stupid but because my mother saw it was important to me it did not matter if it was stupid or not, she just wanted to give me a little happyness.

Hilda recalled throwing John birthday parties every year, buying piñatas and having his friends over, but John's brothers remembered a different Hilda when they were on the witness stand. At John's ROTC parades, Hilda was absent. The four brothers shared a single bedroom and woke most mornings to find Hilda passed out from drinking. They had to dress John and make sure he tied his shoes before school, something they said he sometimes had trouble doing even in high school. Manuel, the oldest, would cook for the boys when he was home, but once he moved out, they often had to fend for them

selves, eating whatever was around. John's younger brother Rodrigo remembered getting a book as a gift for Christmas one year, and a Tonka toy. Those are the only Christmas presents he ever recalled receiving from Hilda. John's uncle Juan painted an even bleaker picture, based on the time he lived with them: John went to school wearing dirty clothes, birthdays were not celebrated, and as for Christmas, “We had no Christmas tree, we had no presents, we had nothing.”

Brownsville has ranked several times as the poorest city in the United States. As of the most recent census, more than a third of its residents lived below the poverty level, with a population that was 93 percent Hispanic, the vast majority of Mexican descent. The region's institutions of higher education have historically been underfunded by legislators in Austin. There is no law school here, or for 250 miles within the United States, and only after decades of battles has a medical school at last been planned. As an outgrowth of this, the region has lacked doctors who specialize in mental health. To become a professional in medicine or law, the best and brightest have continuously been drawn far away. If they stay in Brownsville, they often find that they cannot realize their aspirations because the tools to do so are simply nonexistent.

In a city of such overwhelming poverty, John and his brothers' lives may not have been so unique. Many families struggled to feed their children, and getting government lunches at school was not the exception but the norm. Parents worked late hours or lived in Mexico and sent their children to live with a relative, so a lack of homework help wasn't unusual. In one way, such children might have seen themselves as fortunate: they weren't among their classmates who had just crossed

la frontera

from Mexico and spoke no English.

I met one of John's teachers from elementary school, Pablo Coronado Jr. When he'd heard about the case on the news, more than a decade after John left his classroom, he didn't immediately recognize his former student. Then it clicked: he had been a silly little boy in his class during one of his first years as a teacher. John, he remembered, always tried to make his classmates laugh.

Coronado remembered John as a child who was in need of care, whose clothes were often dirty. Sadly, Coronado said, his situation was not unheard of, even in the second grade.

“They come with a lot of baggage already,” he said. Coronado remembered that he tried to begin the process of getting John extra help. He requested a psychological evaluation. In third grade, John was diagnosed as emotionally disturbed and Hilda said John told her he was seeing shadows. She reported this to the Social Security office.

When John heard or saw something strange, he told me that he would ask the person next to him if he or she did, too. Sometimes people said they had. He took such occasions as evidence that unusual forces were in the world that other people were also at a loss to explain. Hilda corroborated this in her testimony, saying that John told her he was the chosen one, but that she didn't see this as a cause for concern.