The Lord Bishop's Clerk

Read The Lord Bishop's Clerk Online

Authors: Sarah Hawkswood

For H.J.B.

June 1143 The First Day

O

ne

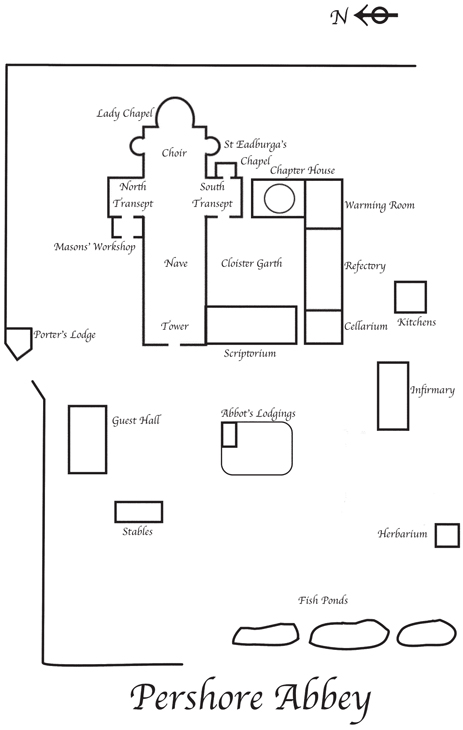

Elias of St Edmondsbury, master mason, stood with the heat of the midsummer sun on broad back and thinning pate, rivulets of sweat trickling down between his shoulder blades. The wooden scaffolding clasped the north transept of the abbey church, close as ivy. Where he stood, at the top, there was no shade from the glare when the noontide sun was so high, and today there was little hint of a breeze. The fresh-cut stonework reflected the light back at him, and his eyes narrowed against the brightness. He turned away, blinking, and then looked down to the eastern end of the abbey foregate, where the usual bustle of the little market town of Pershore was subdued. It was too hot for the children to play chase; many had already sought the cool of the river and its banks, although even the Avon flowed sluggishly, too heat-weary to rush. As many of their seniors as could afford to do so were resting indoors. The midsummer days were long, and the townsmen could conduct their trade well into the cooler evening, though the rhythmic ‘clink, clink’ from the smithy showed that some labour continued. The smith was used to infernal temperatures, thought Master Elias, and probably had not noticed the stultifying heat as he laboured at his craft.

One industrious woman was struggling with a heavy basket of washing she had brought up from the drying grounds to the rear of the burgage plots. She halted to ease her back and brush flies away from her face, then stooped to pick up her load once more. As she straightened she had to step back smartly to avoid being run into by a horseman who rounded the corner at a brisk trot, raising unwelcome earthy red dust as he did so. The man, who rode a showy chestnut, was followed by two retainers. The woman shouted shrill imprecations after the party as they passed from Master Elias’s view, turning along the northern wall before entering Pershore Abbey’s enclave, but he would vouch that they ignored her as they had her now dusty washing.

The scaffolding afforded a grand view of the comings and goings at Pershore, though Master Elias would have taken his hand to any of his men whom he saw gawping in idleness. As master mason, however, he could take the time to survey the scene if he wished. He never failed to be amazed at how much could be learned of the world from the height of a jackdaw’s roost, and he had an eye for detail, which was one of the reasons his skills were so valued. As the sun rose, heralding this hot day, and he had taken his first breath of morning air from his vantage point, he had watched as a troop of well-disciplined horsemen passed through the town, led by a thickset man who rode as if he owned the shire. Master Elias would have been prepared to bet that he did indeed own a good portion of it. Few lords had men with guidons, though he did not recognise the banner. They were also heavily armed, not just men in transit, and they rode with menacing purpose. The latest arrival, in contrast, was a young man in a hurry, for his horse was sweated up and he had not bothered to ease his pace in the heat of the day. His clothing, which proclaimed his lordly status, was dusty, and Elias did not relish the duties of his servants who would have to see to hot horses and grimy raiment before they could so much as contemplate slaking their own thirst.

The nobleman who had arrived earlier in the day had been much more relaxed. He had more men but had ridden in on a loose rein, one arm resting casually on his pommel. Everything about him had proclaimed a man who knew his own worth and had nothing to prove. Something about him was vaguely familiar to Elias, and the thought that he had seen him before was still niggling at his brain. It was a cause of some irritation, like a stone in a shoe. Elias liked everything in order, from his workmen’s tools to his own mind. A question from one of his men dragged both thoughts and eyes away from the world below, and he turned back to the task in hand with a sigh.

![]()

Miles FitzHugh dismounted before the guest hall, head held proud. He rather ostentatiously removed his gauntlets and beat them against his leg to loosen the dust, but then ruined the effect by sneezing. Once the convulsion had passed, he issued terse commands to his long-suffering grooms, who led the horses away to the stables. The young man permitted himself a small smile, enjoying the chance to command others. In his home shire, and away from the entourage of the powerful Earl of Leicester, where he was only one of the young men serving as squires, he could flaunt his own noble birth and status. He had not the insight to realise that this pool, in which he saw himself as the biggest fish, was nothing greater than a stagnant puddle. He entered the cool gloom of the guest hall and, his eyes unaccustomed to the low light, collided with a tall, dark man who made no attempt to step aside. FitzHugh was about to make his feelings known, but his eyes had now made their adjustment, and before the hard glare and raised brows at which he had to look up, remonstration withered on his lips.

‘You should be less hasty, my friend.’ The voice was languid, almost bored, but the word ‘friend’ held a peculiar menace to it.

Taking stock of the man’s clothing, Miles FitzHugh made a rapid alteration to his own manner. ‘My apologies, my lord.’ His voice was refined and precise, but with the deferential tone of one long used to service, and one also used to thinking up excuses swiftly. ‘My eyes have been dazzled by the sun.’

‘Then all the more reason to proceed with caution.’

The tall man was at least a dozen years FitzHugh’s senior, and, by dress and bearing, far superior in rank to a squire, even one in the household of Robert de Beaumont, Earl of Leicester. FitzHugh mumbled an apology and drew aside, almost pressing himself into the hard, cold stone of the whitewashed wall. The older man inclined his head and gave a tight smile as he passed out into the sunlight. The squire would have been galled to have seen how much broader the smile grew once he was in the open.

‘Jesu, was I ever that callow?’ muttered Waleran de Grismont as he crossed the courtyard. His eyes were roving, sharp as a raven’s, taking in everything going on around him. The usual routines within an abbey’s walls were being carried out, as if the monastic world worked on a different level to the secular, aware of its existence but uninterested in its activities. The master of the children was leading his youngest charges to the precentor for singing practice. They followed him with eyes lowered, giving the casual observer the appearance of humility and obedience. De Grismont was amused to see that two lads towards the rear were elbowing each other surreptitiously, and another was picking up small stones and flicking them at a large, pudding-faced boy waddling along in front of him. The perpetrator sensed an adult gaze upon him, and he cast a swift glance in the direction of the tall, well-dressed lord. His eyes met those of de Grismont for an instant, and he grinned, correctly judging that the man would appreciate boldness. The nobleman gave an almost imperceptible nod, and the boy relaxed. The lord clearly remembered the misdeeds of his own youth.

In the shade of the infirmary, a woman was in conversation with the guestmaster. She had an air of competence and efficiency, and seemed perfectly at ease. She was dressed without ostentation, but the cloth of her gown was of fine quality. Her garb, thought de Grismont, was finer than her lineage. Her hands had seen work, and her face and figure were comely but lacking in delicacy. A few years hence and she would be commonplace and plump. He was a man who assessed women frequently and quickly, and he prided himself on his judgement. She held no further interest for him, and he turned the corner to the stables. Had anyone seen him within, they would have found that he looked not to his own fine animal, but to a neat dappled grey palfrey, a lady’s mount. He patted the animal as one who knew it well, and smiled.

![]()

Mistress Margery Weaver knew the guestmaster from previous visits to the abbey, and each understood the manner of the other. In the comparative cool where the infirmary cast its short noontide shadow, she was arranging for payment for her lodging and that of her menservants, who acted as her security when she travelled far from home. In addition, she would leave money for Masses to be said for the soul of her husband. In some ways, she acknowledged to herself, this was a sop to her conscience, because although she had been a loyal and loving wife she was enjoying her widowhood. Her husband had been a man of authority within the weavers’ guild in Winchester, but had died of the flux some three years past. Their son was then only seven years old and so it was Margery who took up the reins of the business, as was accepted by the guild. She came from a weaving family, and had no difficulty in assuming her late husband’s role. What she lacked in bluff forcefulness she made up for in feminine ingenuity, and she had seen the business flourish. She had a natural aptitude for business, and she found it far more interesting than the homely duties of being a wife.