The Lupus Book: A Guide for Patients and Their Families, Third Edition (27 page)

Read The Lupus Book: A Guide for Patients and Their Families, Third Edition Online

Authors: Daniel J. Wallace

ications that can affect liver function, and some abuse alcohol just as nonlupus patients do (which can lead to a chronic active hepatitis), diagnosing autoimmune hepatitis can be tricky. About 30 to 60 percent of those with autoimmune

The Impact of Lupus upon the GI Tract and Liver

[143]

hepatitis also have antibodies to smooth muscle or mitochondria (AMA or

SMA).

How Is Autoimmune Hepatitis Treated?

Why is it so important to split semantic terms to come up with the correct type of hepatitis? Because autoimmune hepatitis, if untreated, can be fatal within 5

years. However, it can respond to agents including steroids and azathioprine.

Several of our patients have undergone successful liver transplants, and we have come a long way in our understanding of liver disease in lupus and autoimmune

hepatitis. But it still takes a great deal of skill to sort out what is an autoimmune disease and what is viral, and thus what medication is appropriate in each case.

Summing Up

Difficulty in swallowing must be taken seriously. Heartburn and acid indigestion can be brought on by medication, stress, or active lupus. Nonspecific bowel

symptoms are common and can be managed symptomatically unless a fever,

localized tenderness, swollen abdomen, or bloody stools are present. These man-

ifestations warrant prompt medical attention. The liver can be involved in lupus because of reactions to medication, antiphospholipid antibodies, or as a complication of infection. Vasculitis in the liver is rare and autoimmune hepatitis should be carefully looked for and ruled out.

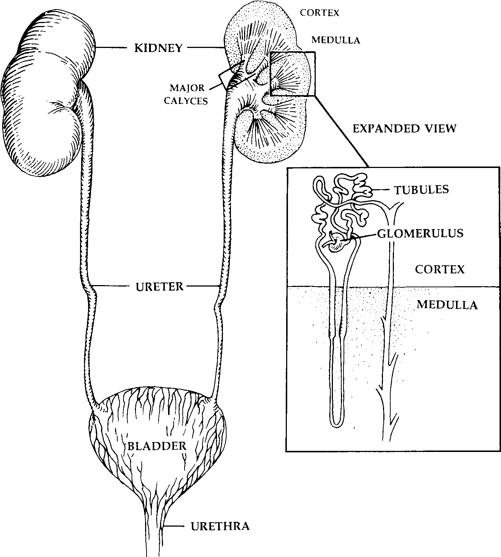

The kidneys are critical to long-term health, and we have come a long way in

understanding how they play a central role in many diseases. Unfortunately, in

up to 40 percent of lupus patients, the disease can affect how the kidneys function. While some do not require treatment, most forms of kidney disease, termed

lupus nephritis

, warrant aggressive management. After discussing the functional anatomy of the kidney, the symptoms and signs of lupus nephritis are reviewed,

followed by a classification of kidney disease and an overview of its therapy.

HOW DOES THE KIDNEY WORK?

Think of the kidneys as the body’s waste treatment plant. The body’s wastes

are filtered by the kidneys and then excreted in urine. The two kidneys are bean shaped organs tucked neatly behind the abdominal cavity, level with the upper

lumbar spine. Blood flows to the

nephron

, the functional unit of the kidney, and each kidney’s approximately 1.2 million nephrons are divided into two parts.

The first part is the

glomerulus

, a series of small, circular corpuscles through which materials are filtered and most reabsorbed back into the blood. The filtrated blood drains into the second part of the nephron, the

tubule

, which both reabsorbs and secretes electrolytes (e.g., calcium, phosphorus, bicarbonate, sodium, potassium, chloride, and magnesium), glucose, and amino acids. These

tubules form into the

ureter

, which connects to the

bladder

—the collecting area of materials destined for excretion. The kidney is principally responsible for

maintaining the volume and composition of body fluids, excreting metabolic

waste products, detoxifying and eliminating toxins, and regulating the hormones that control blood volume and blood pressure. Additionally, it is responsible for helping control the production of red blood cells and cell growth factors.

Lupus primarily affects the glomerulus and produces a condition known as

glomerulonephritis

. Figure 19.1 shows the functional anatomy of the kidney.

Lupus in the Kidney and Urinary Tract

[145]

Fig. 19.1.

The Female Kidney and Urogenital System

HOW CAN YOU TELL WHEN THE KIDNEY IS INVOLVED?

Lupus patients don’t say, ‘‘Doc, my kidney hurts!’’ Pain in the kidney area

would be felt if the patient had developed pleurisy, a kidney stone, or severe

kidney infection, or had suffered a muscular spasm of the lumbar spine. Except

for pleurisy, none of these ailments have anything to do with lupus. In fact,

most patients with kidney involvement have no specific complaints that can be

immediately traced to the kidney. There are two circumstances that initiate

awareness of a kidney problem in SLE patients: when they become

nephrotic

or

uremic

. In nephrotic syndrome, the kidney spills large amounts of protein

[146]

Where and How Can the Body Be Affected by Lupus?

due to a filtering defect and serum albumin levels become very low. When serum

albumin levels drop below 2.8 grams per deciliter (g/dL) or per 100 milliliters and 24-hour urine protein measurements rise above 3.5 grams, swelling is apparent in the ankles and abdomen. Lower amounts of protein loss may result in

mild ankle swelling. The patient may complain of a general sense of bloating

and discomfort. Pleural and pericardial effusions may be noted, and shortness

of breath or chest pains are occasionally present. In uremia, a failing kidney

inadequately filters wastes and toxic materials accumulate, which can damage

other tissues. When a kidney is functioning at a level below 10 percent of

normal, the patient will probably complain of fatigue, look pale, and emit a

distinct odor. Patients suffering from advanced uremia must go on dialysis in

order to live.

Since patients with lupus nephritis usually have few obvious symptoms, how

can we tell whether the kidney is involved? We do it through blood and urine

testing. Elevations in the serum

blood urea nitrogen

(BUN) or

creatinine

usually reflect an abnormality in kidney function and indicate renal involvement. A

urinalysis

is the most accurate assessment for the presence of lupus nephritis.

Patients with SLE have cellular debris called

casts

visible in urine when viewed under the microscope. Many different types of casts can be found, including

hyaline, granular, or red cell casts. Most nephritis patients have

hematuria

, or at least small amounts of microscopic blood in their urine. The most specific

correlate of lupus nephritis is

proteinuria

, or protein in the urine. The presence of protein can be determined quickly and painlessly with a urine test in the

doctor’s office. If proteinuria is found, most physicians attempt to quantitate it by having the patient collect the urine for 24 hours; then the amount of protein in the sample is measured. A spot urine (the urine protein/creatinine ratio) is sometimes used to estimate 24-hour urine excretion. Expect the

24-hour urine

protein

to exceed 300 milligrams when lupus is active in the kidney. Nephrotic patients have protein levels between 3500 and 25,000 milligrams. As part of a

24-hour urine collection, the

creatinine clearance

can be calculated. In theory, creatinine clearance estimates kidney function more reliably than the serum creatinine, but in my experience it is much less helpful and varies by up to 50

percent in a 24-hour period.

WHAT ARE THE TYPES OF LUPUS

GLOMERULONEPHRITIS?

When lupus affects the kidney, it makes sense for a rheumatologist like me to

seek consultation from a kidney specialist (nephrologist) to obtain a renal biopsy.

A renal biopsy is recommended if there is abnormal urine sediment (e.g., casts, hematuria) and more than 500 milligrams of protein in a 24-hour urine specimen.

Renal biopsies have been performed for three reasons: (1) to confirm the diag-

Lupus in the Kidney and Urinary Tract

[147]

nosis of lupus nephritis as opposed to another disease; (2) to determine if the kidney tissue is inflamed, scarred, or both; and (3) to evaluate for potential

treatments. Treating a patient with an elevated creatinine who has significant

scarring but no inflammation with anti-inflammatory medication for the kidney

is not advisable. There is no reason for using potentially toxic medicines without cause.

Tissue obtained at biopsy is examined by three methods. First, it is stained

to look for structural abnormalities and viewed under a standard microscope.

Second, the sample is evaluated for antibodies to the gamma globulins IgG,

IgA, and IgM under an immunofluorescent microscope. Finally, the tissue

specimen is examined with an electron microscope to search for ‘‘electron-

dense deposits,’’ which are immune complexes that interfere with the kidney’s

ability to filter materials properly. Most nephrologists obtain enough material to give the pathologist an opportunity to use all three methods. Occasionally,

only a small amount of tissue is available, which permits a more limited eval-

uation.

These methods allow kidney tissue to be classified according to the

World

Health Organization’s (WHO)

system of six different patterns. In

Class I

, the light microscopy is normal and electron microscopy shows minimal abnormalities. No treatment is indicated.

Class II

disease is termed

mesangial

and reflects mild kidney involvement. Low doses of steroids are sometimes given.

Class III

is called

focal proliferative

nephritis, while

Class IV

is

diffuse proliferative

.

Proliferative disease, both types being extensions of the same process, is a

serious complication and will usually lead to

end-stage renal disease (ESRD)

necessitating dialysis if it is not treated.

Class V

glomerulonephritis is known as

membranous

and is characterized by a high incidence of nephrosis with a tendency towards a slow, indolent, progressive course ending with renal failure if not treated.

Class VI

nephritis is known as

glomerulosclerosis

and represents a scarred down, end-stage kidney with irreversible disease. See Table 19.1.

A doctor can perform a kidney biopsy in a hospital at the bedside or in a

radiology suite with ultrasonic guidance. An ultrasound examination should con-

Table 19.1.

Kidney Biopsy Patterns Found in SLE

10-Year (%) Dialysis

WHO Class

Name

Risk

Treatment

I

Nil disease

Ͻ1%

None

II

Mesangial

10

Low-moderate dose steroids

III

Focal proliferative

50

Steroids, immunosuppressives

IV

Diffuse proliferative

50–75

Steroids, immunosuppressives

V

Membranous

30

Steroids, immunosuppressives

VI

Glomerulosclerosis

High

None

[148]

Where and How Can the Body Be Affected by Lupus?

firm the location of the kidneys and that the patient has two of them. The risk of bleeding from the biopsy in experienced hands is small—1 in 100 patients

needs a blood transfusion and 1 in 1000 will have a serious complication. Most

patients are able to go home within 36 hours of the biopsy without any work

or activity restrictions.

Occasionally, renal biopsies are ill advised or require special preparation.

These circumstances include patients who weigh over 250 pounds (they require

an open biopsy at surgery), patients who are very anemic and/or who cannot

risk blood transfusions (e.g., Jehovah’s Witnesses), or individuals who have

unique clotting problems that predispose them to unusual bleeding risks or re-

quire continuous anticoagulation.

HOW DO WE MONITOR KIDNEY DISEASE?

There is no one test that best assesses lupus in the kidneys. The BUN and

creatinine tell doctors how well the kidney is functioning. High blood pressure signals that the kidney is under stress, and persistent elevations are associated with the development of kidney failure. Low serum albumins and high 24-hour

urine proteins tell physicians how much leakage there is. Low C3 complement

levels and high anti-DNAs in the blood indicate active lupus inflammation. Mi-

croscopic evaluation of a freshly voided urine specimen can roughly suggest

how active the nephritis is. I follow nephritis patients by taking their weight (to measure fluid retention) and blood pressure. Blood and urine are obtained and

a 24-hour urine collection is measured if indicated. These evaluations will reveal a general pattern of improvement, stabilization, or worsening and will suggest