The Mammoth Book of the West (39 page)

Read The Mammoth Book of the West Online

Authors: Jon E. Lewis

The most celebrated woman gambler in the West was “Poker Alice” Tubbs. Born in England inn 1851, the daughter of a schoolmaster, she came to America when she was 12 and at 19 married engineer Frank Duffield in Colorado. After he was killed in a mining accident, Alice took up teaching, and a more profitable dealing of cards in a saloon on a percentage basis. With a cigar in her mouth and a pistol about her person, she was to be seen in many a boom town. She was working for Bob Ford, assassin of Jesse James, when he was shot dead in Creede, Colorado, at which she moved on to Deadwood, working in a saloon alongside another gambler, William Tubbs. One day a drunken miner pulled a knife on Tubbs, but before the blade could be wielded “Poker Alice” shot the miner in the arm with her six-shooter. Inevitably, the pair of gamblers then married. When William Tubbs later died of pneumonia, Poker Alice tried sheep farming before drifting back to the card tables. In 1912 she opened a club near Fort Meade, South Dakota. This was successful until drunken soldiers tried to break in after hours. Fearing she was to be robbed, Poker Alice shot through the door, killing one of the men. At her trial, the judge let her go, declaring: “I cannot find it in my heart to send a white-haired lady to the penitentiary.” She retired to a farm, dying at 79 during a medical operation.

With her cigar dangling from her mouth, Poker Alice was not the only unconformist woman to adopt male mannerisms or conventions. A number took to wearing male clothing, even impersonating men. Not the least reason for doing this was expressed by Elizabeth Jane Forest Guerin (“Mountain Charlie”), who periodically disguised herself as a man: “I could go where I chose, do

many things which while innocent in themselves, were debarred by propriety from association with the female sex.” At the minimum, the donning of male garb placed a woman so far outside expected standards that there was a kind of safety in eccentricity.

Martha Jane Canarray or “Calamity Jane”, was a habitual wearer of male clothing, and according to her own account was an army scout (for the army’s premier Indian fighter, General George Crook) and an army teamster. More likely her connection with the army was as camp follower or prostitute, employed at E. Hoffey’s “hog farm” near Fort Laramie. She was also an alcoholic and notorious liar, who claimed to be married to Wild Bill Hickok. This is unlikely, although she probably knew him in Deadwood. She does seem to have married a Clinton Burke, by whom she had a daughter. Her tendency to vagrancy and brawling saw her arrested several times in mining camps around the West. Her origins are as obscure as the reason for her nickname. She was born anywhere between 1844 and 1852 in Missouri, and her explanation for her soubriquet is that she once rescued a wounded officer, who hailed her as “Calamity Jane, heroine of the Plains.” Her bravery as a nurse is a matter of record; during an outbreak of smallpox in Deadwood she was one of the few to stay behind and help tend the sick. Towards the end of her life she was discovered down and out, working in a brothel in the appositely named Horr, Montana, by Josephine Blake, who persuaded her to take part in the Pan-American Exposition in New York as “Calamity Jane, the Famous Woman Scout of the Wild West.” In 1903, Canarray died in Terry, South Dakota. Friends claimed that her last wish wish was: “Bury me next to Bill [Hickok].” And she was.

Another cross-dresser was Flo Quick, who called herself “Tom King” and rustled cattle in Indian Territory in

the 1880s. Quick was a genuine outlaw. After rustling, she became the mistress of bank robber Bob Dalton, working as the Dalton gang’s spy. As Eugenia Moore or Mrs Mundy, Quick befriended railroad employees, obtaining from them the information about trains the gang intended to hold up. It was Quick who rustled the horses the Daltons used in the Coffeyville disaster in 1892 in which Bob Dalton was killed. Quick then organized her own band before disappearing, although some reports told of her death in a gunfight.

Indian Territory in the 1880s and 1890s saw something of a flowering of women outlaws. The myth-covered Rose of the Cimarron – her real name seems to have been either Rosa Dunn or Rose O’Leary – became an outlaw to share the life of lover George Newcomb (who so frequently sang “I’m a wild wolf from Bitter Creek / And it’s my night to howl” that he was nicknamed “Bitter Creek”). They met when Rose was 15. Allegedly she helped Newcomb escape from a gunfight in Ingalls, Oklahoma, in 1893, when the Doolin gang of which he was a member was trapped by a posse. Realizing that Newcomb was out of ammunition, she hid a gun and cartridge belt beneath her skirt and sneaked them across to where Newcomb was waiting. Newcomb was killed in a gunfight two years later, the assailants being Rose’s brothers, who killed him for the $5,000 reward.

Jennie “Little Britches” Stevens and “Cattle Annie” McDougal were also female associates of Bill Doolin’s gang of “Oklahombres”. They started their careers in crime selling whiskey illegally to Indians in the Osage nation. After that, they tried cattle rustling and horse stealing, and aiding the Doolin gang in their bank robberies. Stevens and McDougal were finally arrested by deputy marshals Bill Tilghman and Steve Burke at a hide-out near Pawnee. The girls resisted arrest, Stevens grabbing a Winchester

and jumping on a horse. Tilghman chased after her, ducking shots. Since the Code of the West did not allow Tilghman to shoot the female fugitive, he downed her horse, and fought Stevens to the ground.

The West’s most infamous female outlaw was Belle Starr, the “Bandit Queen”, also a denizen of Indian Territory. She was born Myra Belle Shirley in Missouri during the troubled era of the border wars. Her first lover was Cole Younger, of the James–Younger gang, who fathered her daughter, Pearl. Soon after, she had another child, Edward (“Eddie”), by Jim Reed. Like Younger, Reed had served as a guerrilla during the Civil War, and had developed a taste for plunder and the illegal pursuit of wealth. He had taken part in at least three of the James–Younger gang’s raids. In 1873 Reed, accompanied by Shirley and another thief, journeyed to Oklahoma, where they tortured a Creek chief until he revealed the whereabouts of $30,000, this being the government’s subsidy to the tribe. Such misdeeds brought the law onto Reed’s trail, and he was obliged to leave Shirley.

When Reed was killed for the $4,000 bounty on his head, Shirley organized her own gang of outlaws in Indian Territory, mostly for the rustling of cattle and horses. In 1876 she took up with Native American outlaw Blue Duck and then with the part-Cherokee Sam Starr, whose surname she adopted, living with him on his small ranch – named by her Youngers Bend – on the Canadian River, which became a refuge for outlaws “on the dodge”.

Belle Starr’s first brush with infamy came in 1883, when she was charged by Judge Parker at Fort Smith with being the “leader of a band of notorious horse thieves.” This was the first time a woman had ever been tried for a major crime in the Western District of Arkansas. Newspapers luridly raised her to celebrity status as “The Petticoat of the Plains” and “The Lady Desperado”, and she played

the part, posing for photographs in a plumed hat sitting on a horse (side-saddle), with a pistol strapped around her waist. Parker found her guilty as charged, and sentenced her to nine months’ imprisonment.

On release, she carried on her illegal trade in horses, and graduated to robbery. In 1886, Belle Starr was again brought before Parker for horse-stealing, but the case was dismissed for lack of evidence. That same year, Sam Starr was killed in a drunken gunfight with an Indian deputy. After Sam Starr’s death, Belle took another common-law husband, the Creek Indian outlaw Jim July. At one point, Belle Starr’s banditry was of sufficient stature to have a $5,000 reward placed on her head “dead or alive”.

Belle Starr was shot in the back by an assassin in 1889. The culprit was probably a neighbour, Edgar Watson, with whom she had quarrelled over land. The other suspect was her son, Ed. According to R. P. Vann, a former member of the Indian police, it was local knowledge that there were “incestuous relations between Belle and her son and that she complicated this with extreme sadism.” By this version, Ed killed his mother to be free of her tyranny.

Belle Starr’s career in crime was long, lasting almost 20 years. That of Pearl Hart was brief and absurd, but she gained fame for participating in the nation’s last stagecoach hold-up. In 1898, while working as a cook in a mining camp, she was persuaded by a drunken miner, Joe Boot, to aid him in the robbery of the stage near Globe, Arizona. They grabbed $431 but then got lost, and a posse caught them three days later. Boot was sentenced to penitentiary for 35 years, Pearl Hart for five. After serving two and a half years, she was released – for good behaviour.

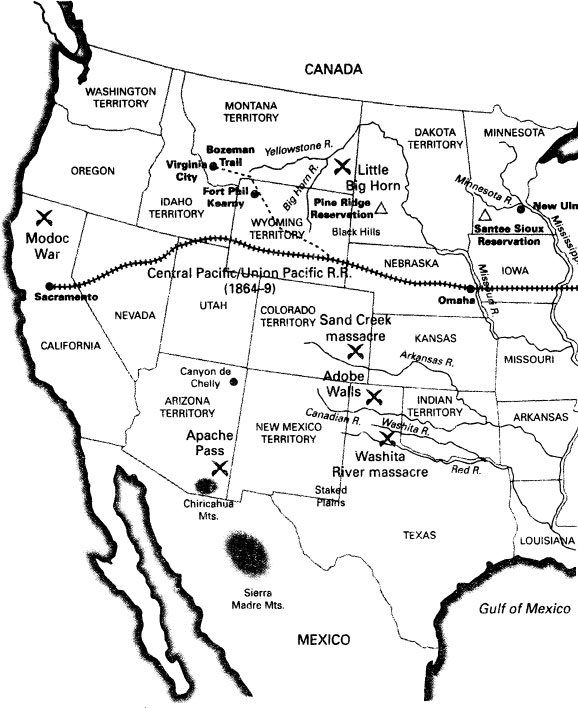

The Indian Wars

5. The Indian Wars

5. The Indian WarsPrologue

. . . these tribes cannot exist surrounded by our settlements and in continual contact with our citizens. They have neither the intelligence, the industry, the moral habits, nor the desire of improvement. They must necessarily yield to the force of circumstance and, ere long, disappear.

There were 10 million Native Americans living in the Americas when the White man landed in the 1490s. The diseases he brought wiped out entire villages, even tribes. The Indians had no immunity to the Europeans’ microbes (or even any indigenous, epidemic diseases to give back to the invader). When the explorers Lewis and Clark met the Mandan at their earth-lodge villages on the bluffs above the Missouri in 1805 the Indians had already suffered one smallpox epidemic, communicated by Indians in contact with the White settlements to the East. In 1837, another smallpox holocaust descended on the Mandan. There were 39 bewildered survivors. The Mandan, to all intents and purposes, had ceased to exist. Other tribes suffered similar catastrophes.

There was more. The White man wanted the Indians’ land. Sometimes he bought it, usually he just took it. Thousands of Indians were killed by war and the famine which resulted. For three centuries, the Indians suffered

pestilence, war and hunger, and fell back and back before the tide of White civilization.

By 1840, there were only 400,000 Indians left in North America. All the eastern tribes had been annihilated, subdued or forcibly removed to Indian Territory, west of the Mississippi. This was to be a permanent Indian domain, inviolable.

No sooner had the permanent Indian frontier been declared than it began to crumble. The westward movement of White settlement had a momentum behind it that could not be stopped by declarations. In 1843 the emigrant trains began crossing the West, invading the “permanent” Indian lands. The discovery of Californian gold sent thousands more stampeding through the Indian hunting grounds in an endless stream of covered wagons and carts, which devastated the grasslands and scared away the buffalo so necessary to the life of the Plains Indian. Angry and despondent, the Indians began to harass the emigrant trains, or exact tributes for the right to pass through their lands.

Government agents in the West began to fear that the desperate Indians would go on the warpath. “What then will be the consequences,” wrote Thomas Fitzpatrick, a former trapper, to his superiors in Washington, “should twenty thousand Indians, well armed, well mounted, and the most . . . expert in war . . . turn out in hostile array against all American travellers?” To forestall this dread possibility, in September 1851 the government called a meeting of all the northern tribes at Horse Creek, 35 miles from Fort Laramie, a remote outpost on the Oregon Trail.

It was the greatest gathering of tribes in history, attended by 10,000 American Indians, camped in the valley in a forest of skin-tents known as tipis. The mighty Teton (from

Titowa

, “plains”) Sioux were there, so were their time-honoured enemies, the Crow. Also in attendance

were the Arikara, Shoshonis, Cheyenne, Assinboine, Arapaho, and the Gros Ventre. Colonel Thomas Fitzpatrick addressed the tribesmen, telling them that the Great Father was “aware that your buffalo and game are driven off, and your grass and timber consumed by the opening of roads and the passing of emigrants through your countries. For these losses he desires to compensate you.” The compensation offered the tribes by the Great Father was $50,000 a year, plus guns, if the Indians would keep away from the trail and confine themselves to designated tracts of land. (Thus began the reservation system, though no one yet called it that.)

The Indians “touched the pen”, and many went away in the belief that an age of harmony between the White and Red people was about to begin. Cut Nose of the Arapaho declared: “I will go home satisfied. I will sleep sound, and not have to watch my horses in the night, or be afraid for my women and children. We have to live on these streams and in the hills, and I would be glad if the Whites would pick out a place for themselves and not come into our grounds.”

Two years later a similar council was held with bands of the Comanche and Kiowa in Kansas. They agreed to refrain from molesting emigrants on the Santa Fe Trail in return for the annuity of $18,000 in goods.