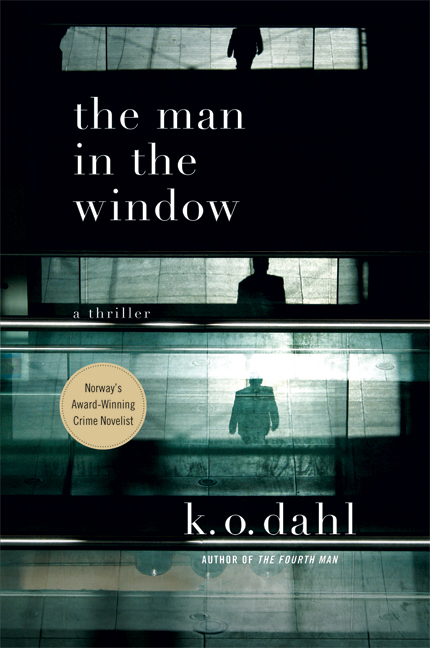

The Man in the Window

Read The Man in the Window Online

Authors: K. O. Dahl

Tags: #Fiction, #Mystery & Detective, #Police Procedural, #International Mystery & Crime, #Noir

The Man in the Window

K.O. Dahl

First published in 2008

by Faber and Faber Limited

3 Queen Square London WC1N 3AU

Typeset by Faber and Faber Ltd

Printed in England by CPI Bookmarque, Croydon, CR0 4TD

All rights reserved

© K. O. Dahl, 2008

Translation © Don Bartlett

The right of K. O. Dahl to be identified as author of this work has

been asserted in accordance with Section 77 of the Copyright,

Designs and Patents Act 1988

ISBN 978-0-571-23291-8

Is this a dagger, which I see before me,

The handle toward my hand? Come, let me

clutch thee: -

I have thee not, and yet I see thee still.

Art thou not, fatal vision, sensible

To feeling, as to sight? Or art thou but

A dagger of the mind, a false creation,

Proceeding from the heat-oppressed brain?

William Shakespeare,

Macbeth,

Act II, scene i

Table of Contents

PART ONE

Friday the 13th

Chapter 1

Lady in the Rain

In the winter gloom of Friday 13th January, Reidar Folke Jespersen started the way he started every day, at least for the last fifty of his seventy-nine years: on his own with a bowl of porridge in the kitchen, his braces hanging loose behind his back and the rhythmic clinks of the spoon against the bottom of the dish as the sole accompaniment to his solitude. He had big bags beneath two bright blue eyes. His chin was covered with a meticulously trimmed, short, white beard; his hands were large, wrinkled and bore sharply defined veins which wound their way up both forearms to his rolled-up shirtsleeves. His arms were powerful; they could have belonged to a logger or a blacksmith.

Reidar had no appetite. In the morning he never had any appetite, but being the enlightened person he was, he understood the importance of the stomach having something to work on. That was why he began every day with a bowl of porridge, which he made himself. If anyone had asked what he thought about during these minutes, he would not have been able to answer. For as he ate, he always concentrated on counting the number of spoonfuls - 23, clink, swallow, 24, clink, swallow. A long life as a porridge-eater had taught him that a bowl would, on average, provide between thirty-eight and forty-four spoonfuls - and if a trace of wonder lingered in his consciousness during these routine-filled moments of the new day, it was only his curiosity about how many spoonfuls it would take to scrape the bowl clean.

While her husband was eating breakfast, Ingrid Jespersen was in bed. She always stayed in bed longer than her husband. Today she didn't get up until half past eight, then she wrapped a white bathrobe around her and scuttled out to the bathroom where the underfloor heating was on full. The floor was so hot it was almost impossible to stand in bare feet. She tiptoed across, then wriggled into the round shower cabinet where she took a long, hot shower. The central heating ensured that the flat was always nice and warm, but as her husband could not tolerate the same temperature in the bedroom, he always turned off the radiator thermostat before going to bed in the evening. Thus the winter cold sneaked in overnight. And even though Ingrid Jespersen was warmly covered by a thick down duvet, she liked to indulge herself with the luxury of a hot shower to awaken her limbs, get her circulation going and make her blood tingle under the surface of her skin. Ingrid would be fifty-four this February. She often fretted at the thought of becoming old, but her appearance never bothered her. Her body was still lithe and supple. These were qualities she ascribed to her days as a dancer and her own awareness of the value of keeping yourself in good physical shape. Her waist was still slim, her legs still muscular, and even though her breasts had begun to sag and her hips no longer had their youthful, resilient roundedness, nevertheless she attracted admiring looks on the street. Her hair was still a natural dark colour with a tinge of red. But her teeth worried her. She, like everyone of her generation, had had poor dental treatment when she was a child. And in two places the fifty-year-old patchwork of fillings had been substituted with crowns.

The most pressing cause of this vanity was that she had a lover, Eyolf Strømsted, a man who had once been her ballet pupil and who was younger than her, and she did not want the age difference to become too conspicuous when she was with him. She turned off the water, opened the cabinet door and went towards the mirror where a grey patina of condensation had formed over the glass. There was still a slight touch of uneasiness when she thought about her lover's reaction to her smile. At first she studied her teeth by grimacing to herself in the mirror. Then she regarded the contours of her body through the film of condensation. She pressed her right hand flat against her stomach and spun half round. She looked at the curve of her back, studied her backside and examined her thigh muscles as she completed the manoeuvre.

Today, though, she stopped in mid-swing. She stood motionless in front of the mirror. She heard the outside door slam. Her husband's going to work without saying goodbye caused her to lose a sense of time and place for a few seconds. The bang of the door disconcerted her and she stared with vacant eyes at her own image in the glass. When at last she pulled herself together, it was to avoid looking at her own nakedness. Afterwards she ran the razor slowly down her right calf but it was an automatic, absent-minded movement, without a hint of the well-being and repose the thought of her lover had evoked minutes before.

The husband, who had long finished his porridge, and had therefore put on his coat and trudged out of the flat without a word, hesitated for a few seconds in front of the door, craned his neck and listened to the sound of running water as he conjured up images of his spouse with closed eyes, droplets forming on her eyelashes, breathing through an open mouth in the stream of scalding hot water cascading over her face. For more than ten years Reidar Folke Jespersen had practised sexual abstinence. The marital partners no longer touched each other. They had no intimate physical contact whatsoever. All the same, their love for each other still seemed to others to have a great tenderness and mutual devotion. This façade was not so very different from the truth for as the couple's erotic love dwindled to nothing, the relationship still rested on a tacit agreement - a psychological contract which contained all the elements of mutual respect and a willingness to accept each other's foibles and quirks, such as putting up with each other's snoring at night - an agreement which also included the ability to do so and the extra strain involved in getting along with a person one assumed one wished well for every hour of the day.

Until three years before, Ingrid had regarded her husband's self-imposed celibacy as a caprice of fate, something she would have to endure in order to apportion due value to the time she had lived in tune with her physical urges. But when, about three years earlier, she allowed herself to be mounted by her ex-ballet pupil, and when the self-same slim, muscular man withdrew his penis, after next to no time, supremely aroused, out of control in his excitement and nervousness, spraying large quantities of sperm over her breasts and stomach, Ingrid Jespersen experienced a feeling of purposeful and satisfied calm. Her daily life was given a new dimension, thanks to the lover. A hitherto ignored, but perceived lack had at long last been addressed and met. She embraced Eyolf with passion. She cradled him in her arms. She stroked his supple back and his muscular thighs. She explored him with closed eyes and sensed the satisfaction of knowing a piece of her life had slotted into place. And for the first time for a long time, as once again she felt her ex-pupil's penis swell between her hands, as the low winter sun cleared the neighbouring block, permitting a sharp ray to penetrate two gaps in the blinds to hit the shelf and a glass penguin - an ornament which broke up the sunbeam into a soft carpet of colours, a rainbow effect, which covered their naked bodies and added a symbolic beauty to her physical enjoyment - at that instant Ingrid Jespersen knew that she was experiencing something which would have a decisive impact on her later life.

Taking it as the most natural thing in the world, the two of them repeated the rendezvous the very next week. Now, three years later, they no longer needed to make any written arrangements; they just met in his flat at the same time, every Friday morning at half past eleven. They had no other contact apart from this visit, triggered and maintained by the same rather painful longing for the other's body and caresses. She looked forward to these weekly assignations with Eyolf in the same way that she would have looked forward to a session with a chiropodist or a psychologist. Meeting him was something she did for her well-being and her mental health. And it never occurred to her that the younger man would see it in any other way. As the weeks and months passed, as rendezvous succeeded rendezvous, they adapted to each other physically and psychologically - from which she derived immense, unalloyed pleasure. She assumed at the same time that he would also find pleasure in this, all the days and nights when he was anywhere else but in the same bed as her.

This morning, after taking a shower, washing her hair, shaving her legs, rubbing cream into her body, varnishing her toe-nails and applying make-up to her cheeks, lips, eyelashes and not least the rather swollen, wrinkled part under her eyes, Ingrid Jespersen once again tightened the dressing gown belt around her waist and went for a stroll through the flat. She stood studying the deep bowl on the kitchen table for a few seconds, the one with the rural pattern from Porsgrund porcelain factory. The remains of porridge, thinned with semi-skimmed milk, covered the bottom of the bowl. She automatically picked it up and rinsed it in the sink. Reidar had put the spoon in the dishwasher. He had put the carton of milk back in the door of the refrigerator. On top of the fridge, neatly folded, lay the morning edition of

Aftenposten.

Reidar had not touched it. The coffee machine on the worktop was full. She poured the contents into a coffee jug. It was half past nine, and she was not due to meet Eyolf for two hours. In half an hour's time, Reidar's son from his first marriage would open his father's antiques shop on the ground floor. It was her intention to take the coffee and go downstairs to the shop, chat to her husband's son and invite him with the rest of his family to dinner that evening. To kill time waiting, she switched on the radio and sat down on the sofa in the living room with the newspaper in front of her.