The man who mistook his wife for a hat (20 page)

Read The man who mistook his wife for a hat Online

Authors: Oliver Sacks,Оливер Сакс

Tags: #sci_psychology

BOOK: The man who mistook his wife for a hat

3.43Mb size Format: txt, pdf, ePub

Such descriptions remained purely anecdotal until the extraordinary studies of Wilder Penfield, half a century later. Penfield was not only able to locate their origin in the temporal lobes, but was able to

evoke

the 'elaborate mental state', or the extremely precise and detailed 'experiential hallucinations' of such seizures by gentle electrical stimulation of the seizure-prone points of the cerebral cortex, as this was exposed, at surgery, in fully conscious patients. Such stimulations would instantly call forth intensely vivid hallucinations of tunes, people, scenes, which would be experienced, lived, as compellingly real, in spite of the prosaic atmosphere of the operating room, and could be described to those present in fascinating detail, confirming what Jackson described sixty years earlier, when he spoke of the characteristic 'doubling of consciousness':

evoke

the 'elaborate mental state', or the extremely precise and detailed 'experiential hallucinations' of such seizures by gentle electrical stimulation of the seizure-prone points of the cerebral cortex, as this was exposed, at surgery, in fully conscious patients. Such stimulations would instantly call forth intensely vivid hallucinations of tunes, people, scenes, which would be experienced, lived, as compellingly real, in spite of the prosaic atmosphere of the operating room, and could be described to those present in fascinating detail, confirming what Jackson described sixty years earlier, when he spoke of the characteristic 'doubling of consciousness':

There is (1) the quasi-parasitical state of consciousness (dreamy state), and (2) there are remains of normal consciousness and thus, there is double consciousness … a mental diplopia.

This was precisely expressed to me by my two patients; Mrs O'M. heard and saw me, albeit with some difficulty, through the deafening dream of 'Easter Parade', or the quieter, yet more profound, dream of 'Good Night, Sweet Jesus' (which called up for her the presence of a church she used to go to on 31st Street where this was always sung after a novena). And Mrs O'C. also saw and heard me, through the much profounder anamnestic seizure of her childhood in Ireland: 'I know you're there, Dr Sacks. I know I'm an old woman with a stroke in an old people's home, but I feel I'm a child in Ireland again-I feel my mother's arms, I see her, I hear her voice singing.' Such epileptic hallucinations or dreams, Penfield showed, are never phantasies: they are always memories, and memories of the most precise and vivid kind, accompanied by the emotions which accompanied the original experience. Their extraordinary and consistent detail, which was evoked each time the cortex was stimulated, and exceeded anything which could be recalled by ordinary memory, suggested to Penfield that the brain retained an almost perfect record of every lifetime's experience, that the total stream of consciousness was

preserved in the brain, and, as such, could always be evoked or called forth, whether by the ordinary needs and circumstances of life, or by the extraordinary circumstances of an epileptic or electrical stimulation. The variety, the 'absurdity', of such convulsive memories and scenes made Penfield think that such reminiscence was essentially meaningless and random:

At operation it is usually quite clear that the evoked experiential response is a random reproduction of whatever composed the stream of consciousness during some interval of the patient's past life … It may have been [Penfield continues, summarising the extraordinary miscellany of epileptic dreams and scenes he has evoked] a time of listening to music, a time of looking in at the door of a dance hall, a time of imaging the action of robbers from a comic strip, a time of waking from a vivid dream, a time of laughing conversation with friends, a time of listening to a little son to make sure he was safe, a time of watching illuminated signs, a time of lying in the delivery room at birth, a time of being frightened by a menacing man, a time of watching people enter the room with snow on their clothes … It may have been a time of standing on the corner of Jacob and Washington, South Bend, Indiana . . . of watching circus wagons one night years ago in childhood … a time of listening to (and watching) your mother speed the parting guests … or of hearing your father and mother singing Christmas carols.

I wish I could quote in its entirety this wonderful passage from Penfield (Penfield and Perot, pp. 687ff.) It gives, as my Irish ladies do, an amazing feeling of 'personal physiology', the physiology of the self. Penfield is impressed by the frequency of musical seizures, and gives many fascinating and often funny examples, a 3 per cent incidence in the more than 500 temporal-lobe epileptics he has studied:

We were surprised at the number of times electrical stimulation has caused the patient to hear

music.

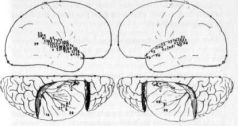

It was produced from seventeen different points in 11 cases (see Figure). Sometimes it was an orchestra, at other times voices singing, or a piano

music.

It was produced from seventeen different points in 11 cases (see Figure). Sometimes it was an orchestra, at other times voices singing, or a piano

AUDITORY EXPERIENTIAL RESPONSES TO STIMULATION.

1. A voice

(14);

Case 28. 2. Voices

(14).

3. 1 voice

(15).

4. A familiar voice

(17).

5. A familiar voice

(21).

6. A voice

(23).

7. A voice

(24).

8. A voice

(25).

9. A voice

(28);

Case 29. 10. Familiar music

(15).

11. A voice

(16).

12. A familiar voice

(17).

13. A familiar voice

(18).

14. Familiar music (19). 15. Voices

(23).

16. Voices (27); Case 4. 17. Familiar music

(14).

18. Familiar music (17). 19. Familiar music

(24).

20. Familiar music

(25);

Case 30. 21. Familiar music

(23);

Case 31. 22. Familiar voice

(16);

Case 32. 23. Familiar music

(23);

Case 5. 24. Familiar music

(Y).

25. Sound of feet walking

(1);

Case 6. 26. Familiar voice (74). 27. Voices

(22);

Case 8. 28. Music

(15);

Case 9. 29. Voices

(14);

Case 36. 30. Familiar sound

(16);

Case 35. 31. A voice

(16a);

Case 23. 32. A voice

(26).

33. Voices

(25).

34. Voices

(27).

35. A voice (28/ 36. A voice

(33);

Case 12. 37. Music

(12);

Case 11. 38. A voice

(17d);

Case 24. 39. Familiar voice

(14).

40. Familiar voices

(15).

41. Dog barking

(17).

42. Music (78). 43. A voice

(20);

Case 13. 44. Familiar voice (i7J. 45. A voice

(12).

46. Familiar voice

(13).

47. Familiar voice

(14).

48. Familiar music

(15).

49. A voice (16); Case 14. 50. Voices

(2).

51. Voices

(3).

52. Voices

(5).

53. Voices (6) 54. Voices

(10).

55. Voices (11); Case 15. 56. Familiar voice

(15).

57. Familiar voice

(16).

58. Familiar voice

(22);

Case 16. 59. Music

(10);

Case 17. 60. Familiar voice

(30).

61. Familiar voice

(31).

62. Familiar voice

(32);

Case 3. 63. Familiar music (8). 64. Familiar music(10). 65.Familiar music

(D2);

Case 10. 66.Voices

(11);

Case7.

(14);

Case 28. 2. Voices

(14).

3. 1 voice

(15).

4. A familiar voice

(17).

5. A familiar voice

(21).

6. A voice

(23).

7. A voice

(24).

8. A voice

(25).

9. A voice

(28);

Case 29. 10. Familiar music

(15).

11. A voice

(16).

12. A familiar voice

(17).

13. A familiar voice

(18).

14. Familiar music (19). 15. Voices

(23).

16. Voices (27); Case 4. 17. Familiar music

(14).

18. Familiar music (17). 19. Familiar music

(24).

20. Familiar music

(25);

Case 30. 21. Familiar music

(23);

Case 31. 22. Familiar voice

(16);

Case 32. 23. Familiar music

(23);

Case 5. 24. Familiar music

(Y).

25. Sound of feet walking

(1);

Case 6. 26. Familiar voice (74). 27. Voices

(22);

Case 8. 28. Music

(15);

Case 9. 29. Voices

(14);

Case 36. 30. Familiar sound

(16);

Case 35. 31. A voice

(16a);

Case 23. 32. A voice

(26).

33. Voices

(25).

34. Voices

(27).

35. A voice (28/ 36. A voice

(33);

Case 12. 37. Music

(12);

Case 11. 38. A voice

(17d);

Case 24. 39. Familiar voice

(14).

40. Familiar voices

(15).

41. Dog barking

(17).

42. Music (78). 43. A voice

(20);

Case 13. 44. Familiar voice (i7J. 45. A voice

(12).

46. Familiar voice

(13).

47. Familiar voice

(14).

48. Familiar music

(15).

49. A voice (16); Case 14. 50. Voices

(2).

51. Voices

(3).

52. Voices

(5).

53. Voices (6) 54. Voices

(10).

55. Voices (11); Case 15. 56. Familiar voice

(15).

57. Familiar voice

(16).

58. Familiar voice

(22);

Case 16. 59. Music

(10);

Case 17. 60. Familiar voice

(30).

61. Familiar voice

(31).

62. Familiar voice

(32);

Case 3. 63. Familiar music (8). 64. Familiar music(10). 65.Familiar music

(D2);

Case 10. 66.Voices

(11);

Case7.

playing, or a choir. Several times it was said to be a radio theme song . . . The localisation for production of music is in the superior temporal convolution, either the lateral or the superior surface (and, as such, close to the point associated with so-called

musicogenic epilepsy).

musicogenic epilepsy).

This is borne out, dramatically, and often comically, by the examples Penfield gives. The following list is extracted from his great final paper:

'White Christmas' (Case 4). Sung by a choir

'Rolling Along Together' (Case 5). Not identified by patient,

but recognised by operating-room nurse when patient hummed

it on stimulation 'Hush-a-Bye Baby' (Case 6). Sung by mother, but also thought

to be theme-tune for radio-programme 'A song he had heard before, a popular one on the radio' (Case

10) 'Oh Marie, Oh Marie' (Case 30). The theme-song of a radio-programme 'The War March of the Priests' (Case 31). This was on the other

side of the 'Hallelujah Chorus' on a record belonging to the

patient 'Mother and father singing Christmas carols' (Case 32) 'Music from Guys and Dolls' (Case 37) 'A song she had heard frequently on the radio' (Case 45) 'I'll Get By' and 'You'll Never Know' (Case 46). Songs he had

often heard on the radio

In each case-as with Mrs O'M.-the music was fixed and stereotyped. The same tune (or tunes) were heard again and again, whether in the course of spontaneous seizures, or with electrical stimulation of the seizure-prone cortex. Thus these tunes were not only popular on the radio, but equally popular as hallucinatory seizures: they were, so to speak, the 'Top Ten of the Cortex'.

Is there any reason, we must wonder, why particular songs (or scenes) are 'selected' by particular patients for reproduction in their hallucinatory seizures? Penfield considers this question and feels

that there is no reason, and certainly no significance, in the selection involved:

It would be very difficult to imagine that some of the trivial incidents and songs recalled during stimulation or epileptic discharge could have any possible emotional significance to the patient, even if one is acutely aware of this possibility.

The selection, he concludes, is 'quite at random, except that there is some evidence of cortical conditioning'. These are the words, this is the attitude, so to speak, of physiology. Perhaps Penfield is right-but could there be more? Is he in fact 'acutely aware', aware enough, at the levels that matter, of the possible emotional significance of songs, of what Thomas Mann called the 'world behind the music'? Would superficial questioning, such as 'Does this song have any special meaning for you?' suffice? We know, all too well, from the study of 'free associations' that the most seemingly trivial or random thoughts may turn out to have an unexpected depth and resonance, but that this only becomes evident given an analysis in depth. Clearly there is no such deep analysis in Penfield, nor in any other physiological psychology. It is not clear whether any such deep analysis is needed-but given the extraordinary opportunity of such a miscellany of convulsive songs and scenes, one feels, at least, that it should be given a try.

I have gone back to Mrs O'M. briefly, to elicit her associations, her feelings, to her 'songs'. This may be unnecessary, but I think it worth trying. One important thing has already emerged. Although, consciously, she cannot attribute to the three songs special feeling or meaning, she now recalls, and this is confirmed by others, that

she was apt to hum them,

unconsciously, long before they became hallucinatory seizures. This suggests that they were

already

unconsciously 'selected'-a selection which was then seized on by a supervening organic pathology.

she was apt to hum them,

unconsciously, long before they became hallucinatory seizures. This suggests that they were

already

unconsciously 'selected'-a selection which was then seized on by a supervening organic pathology.

Are they still her favourites? Do they matter to her now? Does she get anything out of her hallucinatory music? The month after I saw Mrs O'M. there was an article in the

New York Times

entitled 'Did Shostakovich Have a Secret?' The 'secret' of Shostakovich, it was suggested-by a Chinese neurologist, Dr Dajue Wang-was

New York Times

entitled 'Did Shostakovich Have a Secret?' The 'secret' of Shostakovich, it was suggested-by a Chinese neurologist, Dr Dajue Wang-was

the presence of a metallic splinter, a mobile shell-fragment, in his brain, in the temporal horn of the left ventricle. Shostakovich was very reluctant, apparently, to have this removed:

Since the fragment had been there, he said, each time he leaned his head to one side he could hear music. His head was filled with melodies-different each time-which he then made use of when composing.

X-rays allegedly showed the fragment moving around when Shostakovich moved his head, pressing against his 'musical' temporal lobe, when he tilted, producing an infinity of melodies which his genius could use. Dr R.A. Henson, editor of

Music and the Brain

(1977), expressed deep but not absolute scepticism: 'I would hesitate to affirm that it could not happen.'

Music and the Brain

(1977), expressed deep but not absolute scepticism: 'I would hesitate to affirm that it could not happen.'

After reading the article I gave it to Mrs O'M. to read, and her reactions were strong and clear. 'I am no Shostakovich,' she said. 'I can't use

my

songs. Anyhow, I'm tired of them-they're always the same. Musical hallucinations may have been a gift to Shostakovich, but they are only a nuisance to me.

He

didn't want treatment-but I want it badly.'

my

songs. Anyhow, I'm tired of them-they're always the same. Musical hallucinations may have been a gift to Shostakovich, but they are only a nuisance to me.

He

didn't want treatment-but I want it badly.'

I put Mrs O'M. on anticonvulsants, and she forthwith ceased her musical convulsions. I saw her again recently, and asked her if she missed them. 'Not on your life.' she said. 'I'm much better without them.' But this, as we have seen, was not the case with Mrs O'C, whose hallucinosis was of an altogether more complex, more mysterious, and deeper kind and, even if random in its causation, turned out to have great psychological significance and use.

With Mrs O'C. indeed the epilepsy was different from the start, both in terms of physiology and of'personal' character and impact. There was, for the first 72 hours, an almost continuous seizure, or seizure 'status', associated with an apoplexy of the temporal lobe. This in itself was overwhelming. Secondly, and this too had some physiological basis (in the abruptness and extent of the stroke, and its disturbance of deep-lying emotional centres' uncus, amygdala, limbic system, etc., deep within, and deep to the temporal lobe), there was an overwhelming

emotion

associated with the

emotion

associated with the

seizures and an overwhelming (and profoundly nostalgic) content-an overwhelming sense of being-a-child again, in her long-forgotten home, in the arms and presence of her mother.

Other books

Attorney-Client Privilege by Young, Pamela Samuels

ROMULUS (The Innerworld Affairs Series, Book 1) by Marilyn Campbell

Mister Pepper's Secret by Marian Hailey-Moss

Water's Wet Erotica (Seven Stories: Including Virgin to Vixen Series) by Waters, Crystal C.

Every Girl Gets Confused by Janice Thompson

The Fleet Book 2: Counter Attack by David Drake (ed), Bill Fawcett (ed)

FightingforControl by Ari Thatcher

What Might Have Been: Daniels Brother #4 (Daniels Brothers) by Sherri Hayes

Magnet & Steele by Trisha Fuentes

Earning Yancy by C. C. Wood