The Man Who Sees Ghosts (15 page)

Read The Man Who Sees Ghosts Online

Authors: Friedrich von Schiller

What accusations! And the tone used! I took the letter and read it through again—I wanted to find something in it that might mollify him but I found nothing—it was quite inexplicable.

Z*** then reminded me of the secret inquiries that had been made of Biondello a while back. The time, their nature and all the circumstances fitted. We had wrongly ascribed this to the Armenian. Now it was clear who was responsible. Apostasy!—But in whose interests can it be to level such detestable and downright slanders at my master? I am afraid it is a ploy on the part of the Prince von **d***, who wants to bring about our master’s removal from Venice.

The Prince was still silent and staring fixedly in front of him. His silence alarmed me. I went down on my knees before him. “For heaven’s sake, my lord,” I cried, “Do not contemplate anything violent. You must, you will obtain total satisfaction. Let me deal with this matter. Send me back. It is beneath your dignity to answer such charges, but allow me to do so. The slanderer must be named and the eyes of *** opened.

It was in this situation that Civitella found us; astonished, he asked the reason for our dismay. Z*** and I said nothing. But the Prince, who for some while now has no longer made any distinction between him and us and who was also in too towering a rage to give heed to discretion, told us to inform him about the letter. I hesitated for a moment but the Prince tore it out of my hand and gave it to the Marchese himself.

“I am in your debt, Marchese,” the Prince began after Civitella had read the letter with astonishment, “but have no fear. Give me an extension of just twenty days and you shall be satisfied.”

“My Prince,” exclaimed Civitella, mightily moved, “have I deserved this?”

“You did not wish to remind me; I acknowledge your delicacy and thank you. As I said, in twenty days you shall be fully satisfied.”

“What is this?” Civitella asked me in great consternation. “What is the connection? I don’t understand.”

We explained to him what we knew. He was beside himself. The Prince, he said, must insist on redress; it was an outrageous insult. In the meantime he swore to him that he would unconditionally put all his fortune and credit at his service.

The Marchese had left us and the Prince had still not said a word. He was striding up and down the room; something strange was labouring inside him. At last he stopped and muttered to himself between his teeth: “Count yourself fortunate—he said—He died at nine o’clock.”

We looked at him amazed.

“Pray for good fortune for yourself,” he continued. “Fortune—I should pray for good fortune for myself—Did he not say that? What did he mean by that?”

“What makes you think of that now?” I exclaimed. “What has that got to do with this?”

“I did not understand at the time what he meant. Now I do.—Oh, it is unbearably hard being under someone’s authority!”

“My dear Prince!”

“One who can make you smart under it!—Ha! That must be a sweet feeling!”

He paused again. I was shocked by his whole manner. I had never seen him like this.

“The most wretched creature in the land,” he resumed, “or the next in line to the throne! There is no difference. There is but one thing that sets people apart—obedience or rulership!”

He scanned the letter again.

“You have seen the man,” he continued, “who had the impudence to write this to me. Would you greet him in the street, if fate had not made him your master? By heavens! It is a great thing, a crown!”

It continued in this fashion and words were spoken that I cannot entrust to a letter. But the Prince took this occasion to reveal to me a circumstance which astonished and frightened me in no small measure and which could have the most dangerous consequences. Until now we have been grossly mistaken regarding family relations at the *** Court.

The Prince answered the letter straightaway, despite my

vigorous opposition, and the manner in which he did so does not offer any hope of an amicable settlement.

You will also be eager to learn something positive at last about the Greek lady, my dear O**, but it is precisely on this subject that I still cannot give you any satisfactory information. Nothing can be gleaned from the Prince because he has been drawn into the secret and, I assume, has had to make an undertaking to keep it. What is known, however, is that she is not the Greek we took her for. She is German and of the noblest descent. A certain rumour I tracked down has it that her mother is of very high lineage and that she is the fruit of an unhappy love affair much talked about in Europe. The story goes that secret snares set by those in power forced her to seek refuge in Venice and that it was these, too, that account for the concealment that made it impossible for the Prince to find out where she was staying. The respect with which the Prince speaks of her and certain considerations he shows towards her would seem to lend substance to this speculation.

A terrible passion binds him to her and this grows by the day. The visits he was granted at first were sparing; but already in the second week the intervals of separation became shorter and now not a day goes by without the Prince being there. Whole evenings fly by without our seeing so much as a glimpse of him; and even when he is not in her company, it is she alone who occupies his thoughts. His whole being seems transformed. He goes about like someone in a dream and nothing of what formerly interested him can attract from him anything but the most perfunctory attention.

Where will this lead, my friend? The future fills me with dread. The rupture with his Court has made my master humiliatingly dependent on one single individual, the Marchese Civitella. He is now the lord of our secrets, of all our fates. Will he continue to be as noble-minded as he demonstrably still is at the moment? Will these friendly terms continue in the long run, and is it a good thing to entrust a man, even the most excellent, with so much importance and power?

A fresh letter has been sent to the Prince’s sister. I hope to be able to report its success in my next letter.

The Count of O*** continued

This next letter, however, never arrived. Three whole months went by before I received news from Venice—the reason for this interruption will become only too clear from what follows. All my friend’s letters to me had been withheld and suppressed. My dismay can be imagined when, in December of this year, and only by a happy chance (because Biondello, who was to deliver it, became ill suddenly) I finally received the following note. ‘You haven’t written. You don’t reply—Come, oh, come on the wings of friendship. We have lost all hope.

‘The Marchese’s wound is said to be fatal. The Cardinal is intent on revenge and his assassins are hunting for the Prince. My master—oh, my unhappy master!—Has it come to this? A shameful, terrible fate! We have to hide from murderers and creditors as if we were villains.

‘I am writing to you from the cloister of *** where the Prince has found refuge. He is lying next to me on a hard bed and sleeping as I write—ah, the sleep born of

the most deathly exhaustion, a sleep which will serve to strengthen him only to a renewed sense of his sufferings. For the ten days when she was ill his eyes did not close once in sleep. I was present at the post-mortem examination. Traces of poison were found. She is to be buried today.

‘Oh, my dear O***, my heart is in shreds. I have witnessed a scene that will remain for ever in my memory. I stood at her death-bed. She departed this life like a saint and her last, dying words she spent in seeking to bend the steps of her beloved towards the same path that she was taking to heaven—All our steadfastness drained out of us; only the Prince stood firm, and although he suffered her death three times over, he retained enough strength of mind to refuse the pious lady this last request.’

Enclosed with this letter was the following decision:

To the Prince von *** from his sister.

The Church that alone bestows salvation and which has made such a brilliant conquest of the Prince von *** will also not fail him regarding the means whereby he may continue that way of life to which it owes this conquest. I have tears and prayers for him who has gone astray, but no more charity for him who is unworthy.

Henriette ***

I took the very next mail-coach, travelling day and night, and was in Venice by the third week. My haste was of no use to me. I had come to bring comfort and help to an unhappy man: I found a happy man in no need of my feeble support. When I arrived, F** was lying ill

and unable to speak; the following note in his hand was delivered to me. ‘Go back, my dear O**, where you came from. The Prince no longer has any need of you, nor of me either. His debts are paid, the Cardinal reconciled, the Marchese restored to health again. Do you remember the Armenian, who succeeded in bewildering us all so much last year? It is in his arms that you will find the Prince, who five days ago—heard his first mass.’

Despite this, I tried to see the Prince but was turned away. At my friend’s bedside I finally heard the shocking story.

*

This harsh judgement of the nimble-witted prince that Baron von F** permits himself here and in some parts of the first letter will be felt to be exaggerated by everyone, along with myself, who has had the good fortune to become more closely acquainted with this prince, and will be put down to the partiality of the young judge in question—

Note by

Count von O***

*

‘What is it, that only those who are about to die can see’—

TACITUS

,

Germania

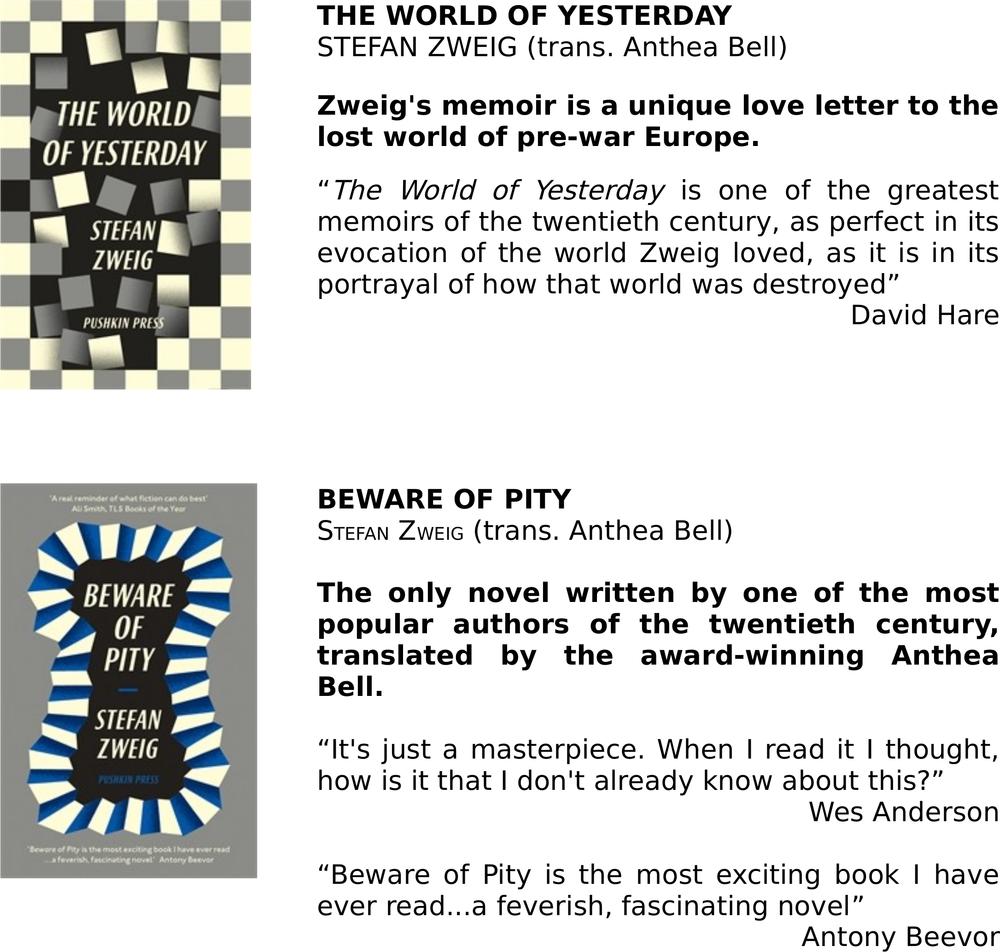

Pushkin Press was founded in 1997, and publishes novels, essays, memoirs, children’s books—everything from timeless classics to the urgent and contemporary.

Our books represent exciting, high-quality writing from around the world: we publish some of the twentieth century’s most widely acclaimed, brilliant authors such as Stefan Zweig, Marcel Aymé, Antal Szerb, Paul Morand and Yasushi Inoue, as well as compelling and award-winning contemporary writers, including Andrés Neuman, Edith Pearlman and Ryu Murakami.

Pushkin Press publishes the world’s best stories, to be read and read again.

Pushkin Press

71-75 Shelton Street, London WC2H 9JQ

English translation © David Bryer 2003

The Man Who Sees Ghosts

first published as a novel in German as

Der Geisterseher

in 1789

This translation first published by Pushkin Press in 2003

This ebook edition first published in 2014

ISBN 978 1 908968 69 2

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without prior permission in writing from Pushkin Press

Cover:

Three Masked Figures in Carnival Costume

(pen & ink on paper) by Francesco Guardi (1712-93)

Museo Correr, Venice, Italy/Bridgeman Art Library (FTB97033)