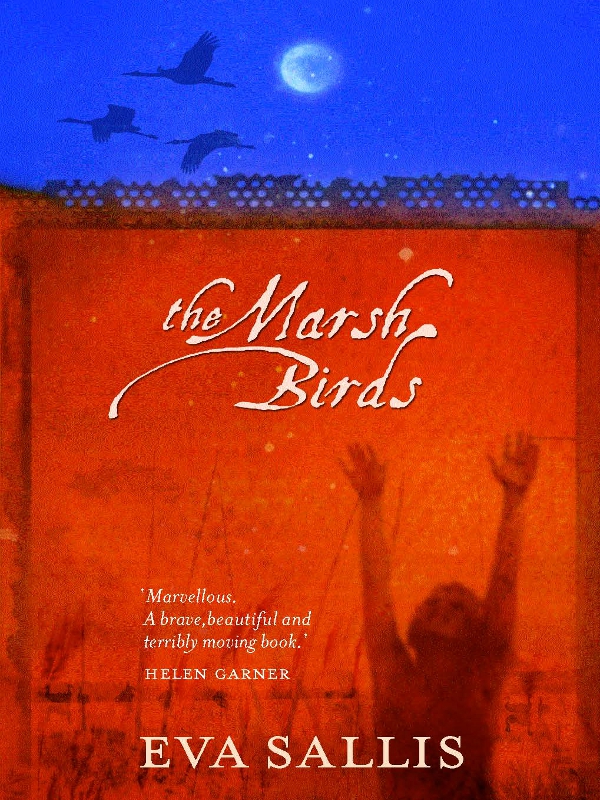

The Marsh Birds

P

RAISE FOR

F

IRE

F

IRE

â

Fire Fire

is vibrant, fiercely intelligent and beautifully written.' Michael Williams,

Australian Book Review

âSlashed with its multiple flashes of refining fire and humour both subtle and ribald,

Fire Fire

is a dark and powerful fable.' Katherine England,

Adelaide Advertiser

P

RAISE FOR

M

AHJAR

âOne cannot praise the timely grace of this book too much.' Michael Sharkey,

The Australian

âSallis writes virtuoso prose which on the surface is deceptively simple, but is remarkable in its psychologically penetrating breadth.' David Wood,

Canberra Times

âSuperb stories, astonishing in their range and power; subtle, brave, unbearably moving.' Helen Garner

âSallis wields her great gifts of empathy and eloquence to render human beings in full, unflinching detail. It is a book of journeys, passionate and powerful.' Geraldine Brooks

P

RAISE FOR

T

HE

C

ITY OF

S

EALIONS

âA rich book â a lyrical account of a girl's growth and self-discovery, and at the same time a deeply sympathetic exploration of Muslim culture.' J.M.Coetzee

P

RAISE FOR

H

IAM

âA debut that is truly stunning.'

Australian Bookseller and Publisher

âIts brilliance, innovation and daring is undeniable.'

Australian Book Review

A

LSO BY

E

VA

S

ALLIS

Fiction

Hiam

(1998)

The City of Sealions

(2002)

Mahjar

(2003)

Fire Fire

(2004)

Non-fiction

Sheherazade through the Looking Glass:

The Metamorphosis of the 1001 Nights

(1999)

Co-edited anthologies

with Brenda Glover, Kim Mann and Scott Hopkins

Painted Words

(1999)

with Rebekah Clarkson, Kerrie Harrison, Gabrielle

Hudson, Lisa Jedynak and Samantha Schulz

Forked Tongues

(2002)

with Heather Millar and Sonja Dechian

Dark Dreams: Australian Refugee Stories by Young Writers

11â20 Years

(2004)

E

VA

S

ALLIS

First published in 2005

Copyright © Eva Sallis 2005

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording or by any information storage and retrieval system, without prior permission in writing from the publisher.

The Australian Copyright Act

1968 (the Act) allows a maximum of one chapter or 10 per cent of this book, whichever is the greater, to be photocopied by any educational institution for its educational purposes provided that the educational institution (or body that administers it) has given a remuneration notice to Copyright Agency Limited (CAL) under the Act.

This project has been assisted by the Commonwealth Government through the Australia Council, its arts funding and advisory board.

Allen & Unwin

83 Alexander Street

Crows Nest NSW 2065

Australia

Phone:Â Â Â Â (61 2) 8425 0100

Fax:Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â (61 2) 9906 2218

Email: Â Â Â Â [email protected]

Web: Â Â Â Â Â Â

www.allenandunwin.com

National Library of Australia

Cataloguing-in-Publication entry:

Sallis, Eva.

The marsh birds.

ISBN 1 74114 600 3.

1. RefugeesâAustraliaâFiction. I. Title.

A823.3

Set in 12/15 pt Bembo by Asset Typesetting Pty Ltd

Printed in Australia by McPherson's Printing Group

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

For the boys I love, especially Roger and Rafael

Contents

D

hurgham's chest hurt. His heart hammered in its bed of pain. It was the third day and all his limbs ached. He had sat on this same block of stone near the main entrance of the mosque, night and day, huddled just enough out of sight to deflect attention, just enough in sight for his mother to see him, instantly, to run to him and cup his face ⦠and then, and then!âit would all be over. His father would wrap his arms around him and squeeze so tight that all the pain left him. He gasped his tears back at the expectancy of it. Now! Now! Right now, they would come around that corner or out of the shadows of the Souq al Hamidiya, hesitant under the broken arch, then breaking into a run. He could see the anger of relief after worry, now! Now!

If we get separated, we meet together at the Great Mosque.

If we get separatedâ

He had slunk around the mosque, expectant and with his heart hammering, always hammering. Three days! He stuck close to the wall. The mosque was the only certain thing.

We meet together at the Great Mosque.

Sometimes he even kept his hands on the corner stones, as if touch more than sight could confirm he had done the right thing. He was certain his father had said the Great Mosque and that in all the world there was no other. This was the greatest, oldest mosque. He knew that, even from school.

He couldn't leave it further than a few steps. After the first three days, he slept in the broken garden near the tomb of Salahuddin, curled up in the darkness against the ancient mosque wall. At night he was afraid. He made himself small against the cold stone, his heart pounding him into the ground, and with the dawn prayers he was on his block of stone again. He could feel his heart breaking.

He couldn't bring himself to go inside. The crowds flowed by him with the adhan and then by him again at the end of prayers. If anyone greeted him, nodded to him to come inside too, Dhurgham answered shyly that he had to wait for his parents. But people mostly ignored him or didn't see him at all.

Occasionally other small boys about his age or younger played in the cobbled square between the mosque and the crumbling entrance to the Souq al Hamidiya. They called out to him a few times, raucouslyâwho was he, what was his father's name, where from, then to come and join them, but to each question he shook his head, suddenly too shy, too alone, to find words. They had funny accents and giggled at him when he spoke. They kicked their soccer ball at him to provoke him into participation, but when the ball struck him and rolled off and away, they gave up. They shouted a few insults at him, shook their heads at him in mimicry, then left him alone.

After that, now and then, he wanted to play. A kind of certainty about the world restored him and his spirits rose. His parents couldn't be that far away. He was going to feel really silly for all his fears when they showed up. He was the first to make it to Damascus, that was all.

I won!

he'd crow to Nooni, and she'd punch him, narrow her eyes at him. And then, when she found out that he'd been a bit scared, she'd say,

You big silly

, and shove him this way and that. The only thing that stopped him playing then was the thought of them catching him being carefree when the situation called for more sedate adult behaviour. There was the money sewn into his blazer to think of. Not a good idea to fold his blazer neatly on the ground and keep an eye on it. To play he would have to hug it close to his body with his hands in his pockets. He would look silly.

On the morning of the fifth day, he thought suddenly that as long as he was in or around the mosque, they would find him. He didn't need to wait at the al Hamidiya entrance. They would go everywhere, they would look for him. He smiled to himself, very pleased. He was clever to guess it. He was certain he was right. He could feel his mother's anxiety, how feverishly she would hunt for him in every possible corner, inside and out, even in the streets around the mosque, even if she herself had to stay there day and night. She was born in Syria, he thoughtânear the border with Iraq, but nonetheless in this same country. He touched the Syrian stones with a new familiarity and was immensely cheered. She would use her Syrian voice, her knowledge of everything Syrian. Everyone would respect and obey her. He felt a light lift to his step and walked again the three quarters way round the mosque and back. He didn't dare go all the way round because the souq and alleys seemed to come right up against the mosque at one point, and he felt himself leaving it behind if he headed around them to find the route back to the other side of the great walls. He really had a lot of space that was safe. And of course there was inside. All safeâa huge realm.

He went round to the side by the garden in which he slept and for the first time turned his back on the possible roads by which his father, mother and sister would arrive (any minute now). He walked in through the great open door. He was sure no one would stop him, even though Damascus was strange in lots of ways. Just inside, he removed his shoes.

The mosque was huge inside, far bigger than its outer perimeter made it seem. It was unbelievably quiet, given the noise outside. Students were reading here and there in the shade of the great arcades that ran to the left and the right, seated on the marble floor that spread like a still lake across to the other side. He felt strangely free. He padded softly along the arcade to the left. He sought out a space free of people and sat down himself on the cool marble. Here he found he could imagine his mother finding him, his father's austere relief, Nura's delight as if these were already events of the long distant past, events remembered with pain and pleasure but with no urgency or terror or doubt. It was nothing really. The mosque was ancient and had seen far greater tragedies and troubles. He could remember some of them from his schoolbooks and beguiled himself for hours with that connection anyone can feel when touching and seeing a place that brings the past into the present.