The Mary Russell Companion (3 page)

Read The Mary Russell Companion Online

Authors: Laurie R. King

Tags: #Mystery; Thriller & Suspense, #Mystery, #Women Sleuths, #Reference, #Writing; Research & Publishing Guides, #Research

England: Sussex, Arley Holt (Berkshire), London, Dorking

France: Paris, Lyons

US: New York

Canada (Ontario): Toronto, Webster

The Game

England: London, Sussex, Kent, Dover

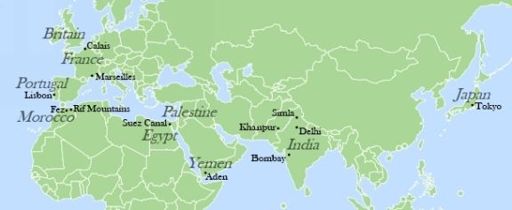

France: Calais, Paris, Marseilles

Egypt: Suez Canal

Yemen: Aden

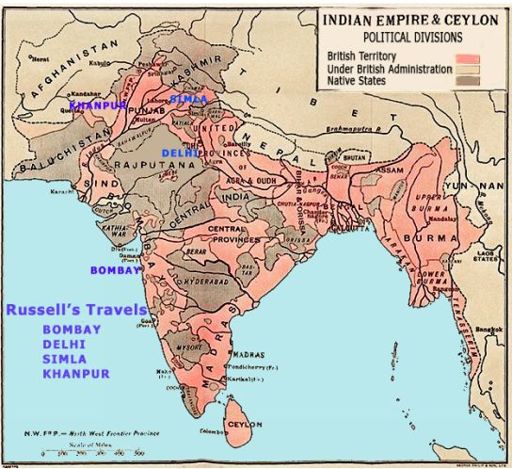

India: Bombay, Delhi, Simla, Khalka, Khanpur

Locked Rooms

Japan: Tokyo (mentioned only)

Hawaii

California: San Francisco, Los Angeles

The Language of Bees

Britain: Portsmouth, Sussex, London, York, Edinburgh, Inverness, Orkneys

The God of the Hive

Britain: Orkneys, Lakes District, London, Edinburgh

Pirate King

Britain: Sussex, London

Portugal: Lisbon, Cintra

Morocco: Salé and Rabat

Garment of Shadows

Morocco: Rabat, Fez, Erfoud, the Rif mountains

A Woman of the Twenties:

Mary Russell, Feminist?

The Twentieth century was a whirlwind of women’s activities. Matters were well under way long before the Great War blew up the well-established structures of the Victorian and Edwardian eras: the Suffragette movement (as opposed to the less assertive Suffrag

ists

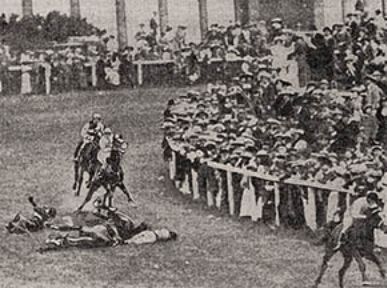

) got under way in 1903, two years after the death of Queen Victoria. The militant wing of women’s rights, under the leadership of the three Pankhursts, mother and daughters, advocated any act short of taking a life—including giving one’s life for the cause. Hunger strikes, willing arrests, suicide under the hooves of the King’s horse—society in general did not approve, but it had to admit that the women were serious.

Suffragette Emily Davison’s suicide(?) at the Epsom Derby

Then came War. The Suffragettes shelved their militant actions for the duration and set about proving themselves in other ways. By the time Armistice was declared, Parliament could no longer deny the right to vote: if women could be trusted to run public transportation, farm the land, and police the streets, surely they could be trusted with the Vote.

The idea of the “New Woman” actually got its start in the nineteenth century, a reference to the independent, educated, and assertive women one found among Society, and especially living the expatriate life in Europe. (It should be noted that in the literature dealing with the New Woman—stories by Henry James being foremost—things rarely end happily for the woman in question.)

The New Woman was a member of the privileged classes—even for men of the times, higher education was rare, and only the daughters of the rich could set up their salon in Paris or Vienna without having a willing husband in tow. However, by the Twentieth century, the dissatisfaction with one’s lot was beginning to extend to the non-privileged classes. The women’s health and birth control clinics of Marie Stopes in the UK and Margaret Sanger in the US reached the lives of the poor (although it must be noted that both women seemed less interested in merely helping than they were in eliminating the “unfit”—i.e., the poor). Early suffrage proponents were as determined to achieve divorce and inheritance reform as they were the actual vote: most women of the time had little consideration of any inheritance, and in any case, not until 1928 were women put on the same footing as men when it came to the Vote.

Marie Stopes

Privilege was the key.

Privilege has always been key in the rights women could claim for themselves. Mary Kingsley celebrated her freedom from caring for aged parents by heading off to West Africa to finish the research on a book her father had been working on. She blithely plunged into jungles, across the rivers, and up mountains (wearing Victorian bombazine and bustles—which, when she fell onto the stakes in a tiger pit, saved her life: “The blessings of a good thick skirt.”), coming home to celebrity. But Kingsley was not interested in feminism, and did not believe women should have the vote while large numbers of men did not.

Mary Kingsley

Gertrude Bell similarly fell in love with life in the wild places, in her case the desert of the Middle East. She became the eyes of British Intelligence, advisor to nations, and was central to the division of Mesopotamia into its modern countries. She also, ironically, was a proponent of the Women’s Anti-Suffrage League—rather as Phyllis Schlafly later made a career out of being against (among other things) career women.

Gertrude Bell

Women like Bell and Kingsley regard themselves as outside the question of sex. And they are so regarded by others: when Bell blithely moved across the face of the desert, she simply assumed that any sheikh, governor, or military general would be pleased to speak with her on equal terms. When Kingsley hired porters and guides to take her into Africa, the men didn’t shake their heads and refuse to take this white woman anywhere. (Although they may have shaken their heads—and admittedly, they may not have recognized this bombazined and be-hatted creature as a female, per se.)

Q: When is a woman not a woman? A: When she is a force of nature.

Mary Russell is both like these women, and different from them. Certainly when we first meet her, she demonstrates more of the wealthy elite’s tendency to blind self-confidence then she does the chronic uncertainty of the usual fifteen year-old girl. When Russell’s editor, Laurie King, speaks of the Memoirs as the coming-of-age story of an extraordinary young mind, this is what she means, not merely the apprenticeship of a clever woman detective.

How does a person go from the shallowness of

I am me

to an attitude of,

I am me, a woman—

then beyond that towards,

I am me, a woman of privilege

?

We can only speculate what might have become of Miss Russell had her parents not died. Would she, too, have gone lightheartedly off into a world where a rich woman and her housemaid have no more in common than the roof under which they both lived?

But her family did die, leaving her to stand alone, questioning the rightness of the universe and the permanence of life. This doubting attitude is further emphasized when she is apprenticed to a man who questions everything he sees. Russell is driven towards self-awareness in ways Gertrude Bell never faced—or, faced only when she was long beyond the flexibility of youth.

So, if feminism means an awareness that privilege is given, not deserved; that fairness is an ideal, not a state; that when a man and a woman do the same job, they should receive the same pay, then yes: Mary Russell is a feminist.

On Matters Unspoken

One element of the Russell & Holmes memoirs that excites considerable interest among her readers is the question of the marital relations between the principals. Generally speaking, Russell is decorous when it comes to personal revelation, although she does admit (

A Letter of Mary

) that Holmes is “as energetic and scrupulously attentive to detail in the physical aspects of marriage as ever he was in an investigation or laboratory experiment”, then adds that he was “not otherwise a man demonstrative of his affections.” In

Locked Rooms,

Russell says that not only was she “well matched mentally” to Holmes, she was also “well suited physically, to a man who interested my intellect, challenged my spirit and roused my passions.”