The Mary Russell Companion (31 page)

Read The Mary Russell Companion Online

Authors: Laurie R. King

Tags: #Mystery; Thriller & Suspense, #Mystery, #Women Sleuths, #Reference, #Writing; Research & Publishing Guides, #Research

Pain was a thing the greens-man could deal with.

He stepped from the trees, permitting a branch to whisper against his sleeve. The startled boy gaped at this figure born of the woods: a man with too-long hair and untidy beard, whose clothes might have been woven from the branches behind him, who waited, at a distance, palms outstretched, saying nothing. The boy dashed the moisture from his cheeks, and his sharp fear subsided into wariness

The man came forward. He dropped to his heels, holding the boy’s eyes, and stretched out his hands in invitation. Hesitant, the boy’s supporting hand loosened, then fell away. The man’s fingers took a moment to confirm what his eyes had told him, and he sat back on his heels to talk the boy calm.

“It’s dislocated. I can fix it for you, but it’ll hurt like the devil for a moment. Afterwards it will be just sore. I knew a man during the war who had a shoulder just like yours. He drove a team of horses at the Front, hauling shells, wire, equipment. A German shell landed while he was unloading the wagon. The horses panicked and he reached out for them as they bolted. Yanked his shoulder right out its socket.”

The man went on for a time, embroidering a thread of heroism into the story, while the boy tried to wrap his mind around the idea of further pain. But he was a brave lad, and trusting, and eventually he gave his permission by saying, “He didn’t mean to do it. My Da’.”

The man kept his eyes from the raw swollen mouth, and rose to do what had to be done.

When it was over, when fresh tears were stinging their way into the half-sealed scabs on his face, the boy’s face wore the same look that the driver’s had: wonder, relief, and gratitude, a mix indistinguishable from joy.

He sent the boy on his way, and followed, silent this time as a woodland pool. The boy paused at the edge of a walled pasture, then trudged manfully towards the unkempt farmyard below. The woods-man watched as the farmer came out of the cowshed, crowded up to the boy, cuffed him to the ground, and went inside. He watched the boy pick himself from the ground, and follow.

At dawn the next day, the farmer went to milk his cow. When the farmer’s wife went to see what was keeping her husband, she found him on the muck-strewn floor, his head stove in by a tidy bash the size of a cow’s hoof. The milking stool stood upright, a full pail of milk beside it, a silver coin on its top.

From then on, every so often a silver coin was found, here and there around the farm.

A god is born at the intersection of need and torment, and brings joy where he can.

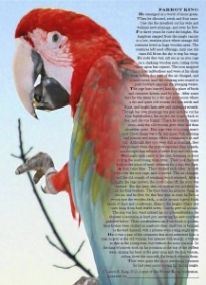

Parrot King

Parrot King

was a part of the 2011

Pirate King

celebration, arranged on the page to permit for illustrations

.

These are by Shirley Bomgaars, Veronica Adrover, Debra C. Thomas, and Jenny Parks; more can be found on the Laurie R. King website.

Parrot King

Parrot King

H

e emerged in a world of moist green.

When he shouted, seeds and fruit came.

One day he stretched out his wide and

brilliant new plumage, and away he flew.

F

or three years he ruled the heights. His

kingdom ranged from the jungle canopy

to a low, treeless place where strange dull

creatures lived in huge wooden nests. The

creatures left seed offerings, until one day

vines fell from the sky to trap his wings.

H

e rode the vast, salt sea in an iron cage

on a stinking wooden nest, calling down

curses upon his captors. The iron snapped

his scarlet tailfeathers and wore at his sharp

beak before the taste of the air changed, and

sounds arose, and the creaking nest ceased to

push forward through the plunging waters.

T

he cage bars carried him to a place of birds

and creatures driven mad by iron. After some

days he was taken to a dry and quiet room where

a dry and quiet old woman fed him seeds and

fruits, and taught him new and appealing sounds.

Though her own plumage was grey and she cut his

blue flightfeathers, he recited the sounds back to

her, and she was happy. There he lived for many

years, until the old woman grew drier and then

altogether quiet. His cage went to a young man’s

nest where things were far less quiet, with shouting

and passion and many others continuously in and

out. Although they too were dull in plumage, they

were pleased when the parrot repeated their sounds,

and brought him tribute of sweet fruit and rich nuts.

O

ne night men came to the nest, breaking its door

to drag the loud young man away. They took the bird

back to the place of mad creatures for a day, two days.

A

man came then. They studied each other. A cloth

went over the iron cage, and it moved. The air changed,

and the old sounds of creaking wood returned. After a

night, the cage moved, the cloth came off, the door was

opened. But this time, the old woman was not there to

clip the blue feathers. The bird beat his glorious wings in

the air, and he flew, for the first time in years he flew—a

swoop past the wooden deck, a circle around a great black

ripple of skull and crossbones, then to the heights where taut

vines hung from bare-leafed trees. Canvas grew all around.

The sun was hot; wind tickled his royal breastfeathers; he

shouted a recitation in hard joy, surveying his new courtiers

gathered below. Their crestfeathers ran from black to golden;

their bodies were clothed in rainbow; their chief was as brilliant

as the bird himself, with a plume even a king might envy.

B

ut it was a pair of the creatures that most interested him: a

man as grey as the old woman, but intense with energy, a woman

as thin as the young man, but without the noisy passion. So

the king of parrots took up his position at the top of the leafless

trees, tipping his head at the grey man and the thin woman,

sidling down the smooth, flat branch towards them.

T

hey were quite the most interesting creatures

he had seen since leaving his distant jungle.

—Laurie R. King

Illustrations by Shirley Bomgaars, Veronica Adrover, Debra C. Thomas

Interview IV

A Twentieth Anniversary Conversation

In celebration of the twenty years since the publication of

The Beekeeper’s Apprentice

, Laurie King sat down on the terrace to interview Mary Russell. Or, she tried

.

Interview on the terrace

LRK:

Thank you for that tour, the garden is looking beautiful.

MRH

: It is, isn’t it? Tea? Oh, Mrs Hudson? Might we have some of your shortbread biscuits as well? Thank you.

LRK

: Oh, yes please! I do remember these, they’re fabulous.

MRH

: A recipe from the first Mrs Hudson.

LRK

: Her granddaughter does—

MRH

: Great-granddaughter, in law.

LRK

: Right. Well, this Mrs Hudson does the earlier proud. No, thanks, I won’t take honey. Although I’m glad the bees seem to be doing well.

MRH

: Yes, so far Holmes has avoided the worldwide hive plague. He has a number of theories why—

LRK

: (

sotto voce

) Of course he does.

MRH

: —but essentially he finds it best to treat Nature as Nature has developed over the centuries. The potentially dire consequences of modern agriculture encourage one to be conservative.

LRK

: An interesting statement from a renowned iconoclast and experimenter. Is this thing working? Yes, looks like. Shall we get started? Good morning, Miss Russell. Happy anniversary!

MRH

: Of what is this the anniversary?

LRK

: Your publication—or, I suppose, ours. Believe it or not,

The Beekeeper’s Apprentice

came out twenty years ago.

MRH

: I do believe it. I hear of myself everywhere, since you became my ‘chronicler.’

LRK

: The

Greek Interpreter

!

MRH

: I beg your pardon?

LRK

: Oh, nothing. I hope you don’t mind, that you have become rather famous?

MRH

: It was inevitable, once I decided to send the manuscripts to you. My name has even appeared in our local newspaper. Although the world does still seem determined to believe that these are novels, rather than memoirs.

LRK

: Yes, I am sorry about that, but the publishers—

MRH

: However, I will admit that my feelings about that oddity have changed somewhat, of late.