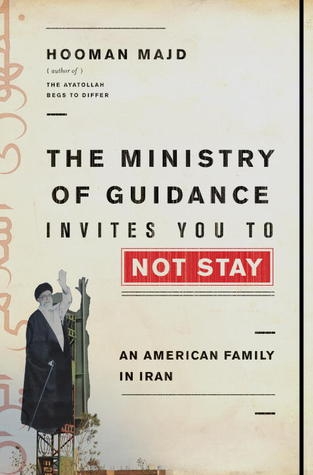

The Ministry of Guidance Invites You to Not Stay: An American Family in Iran

Read The Ministry of Guidance Invites You to Not Stay: An American Family in Iran Online

Authors: Hooman Majd

Tags: #Political Science, #International Relations, #General, #Biography & Autobiography, #Personal Memoirs, #Social Science

Copyright © 2013 by Hooman Majd

All rights reserved. Published in the United States by Doubleday, a division of Random House, Inc., New York, and in Canada by Random House of Canada Limited, Toronto.

DOUBLEDAY

and the portrayal of an anchor with a dolphin are registered trademarks of Random House, Inc.

Jacket photo © Kaveh Kazemi/Contributor/Hulton Archive/Getty Images (Image #105202495)

Jacket design by Michael J. Windsor

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Majd, Hooman.

The Ministry of Guidance invites you to not stay :

an American family in Iran / Hooman Majd.—First Edition.

pages cm

1. Iran—Politics and government—1997– 2. Iran—Economic conditions—1997– 3. Iran—Social conditions—1997– 4. Majd, Hooman—Travel—Iran. 5. Iranian Americans—Iran—

Biography. 6. Americans—Iran—Biography. I. Title.

DS318.9.M356 2013

955.06′10922—dc23

[B] 2013002552

ISBN 978-0-385-53532-8

eISBN 978-0-385-53533-5

v3.1

For Khashayar

In memoriam Nasser Majd

(1928–2012)

The inhabitants of Tehran are invited to keep quiet.

—ATTRIBUTED TO SHAH REZA KHAN PAHLAVI

If I sit in silence, I have sinned.

—MOHAMMAD MOSSADEQ

CONTENTS

CONTENTS

Cover

Title Page

Copyright

Dedication

Epigraph

Prologue

1. A TASTE OF THINGS TO COME

2. TOUCHDOWN

3. WE LOVE YOU (US EITHER)

4. THE BIG SULK

5.

FARDA

6. BEATING THE SYSTEM

7. A FUNNY THING HAPPENED ON THE WAY TO THE REVOLUTION

8. JUDGE NOT

9. FIGHT FOR THE RIGHT TO PARTY

10. ROAD TRIP!

11. POLITRICKS

12. HOME

Postscript

Acknowledgments

A Note About the Author

Other Books by This AuthorPROLOGUE

“Hello?” I didn’t recognize the number of the incoming call on my cell phone, but it was from Washington, D.C., so I answered, standing on a deserted stretch of the waterfront in Greenpoint, Brooklyn, on a September day in 2010.

“

Agha-ye Majd?

”

“

Baleh?

” I answered, yes—in Farsi, since the caller was obviously Persian.

“I’m calling from the Iranian consulate, and I have a question about your applications for your wife and child.”

“Yes?” I said.

“You were married, it seems, after your child was born,” the lady said. My longtime girlfriend and I had had a son a few months prior, and we had finally gotten married in a civil ceremony a month before he was born. Realizing that in order to get them Iranian citizenship and passports, we had to be married in an Islamic ceremony—even before the Islamic Revolution, the only marriage Iran recognized was a religiously sanctioned one—we had done exactly that, three months later, at the Islamic Institute of New York, which shares a building with the Razi School (“Academic Excellence in a Distinctive Islamic Environment”!) in Queens. My wife was instantly converted

to Islam, Shia Islam, as required. The mullah had patiently explained then, in Farsi while begging me to translate, that converting didn’t mean rejecting Christianity or Jesus Christ; it only meant that my wife was accepting Mohammad as the last in line of the holy Abrahamic prophets.

Yeah, whatever, let’s do this

. That was what my wife’s expression had communicated from under a hastily improvised head scarf consisting of our son’s monkey-print blanket. I hadn’t realized that scarves were mandatory, although I should have checked the Razi School Web site, where the uniform for girls is listed as “navy overcoat, white scarf.” Meanwhile, our son, now deprived of his blanket, screamed and farted in what sounded to me like pretty good harmony. “How about Buddha?” my wife wondered. She told me to tell the mullah she accepted

him

, too. I nodded and ignored her request.

The lady calling me now was from the Iranian Interests Section at the Embassy of Pakistan in Washington, D.C., the office that handles the consular affairs of Iranians in the United States in the absence of diplomatic relations between the two countries. She was technically incorrect in identifying herself as “from the consulate,” since there is actually no such thing as an Iranian embassy or consulate on American soil, but it was a minor technicality; the Interests Section was authorized to issue citizenship papers for Iranians born in the United States and to issue passports to American wives of Iranian citizens—but not to American husbands of Iranian wives, or to children of those unions, who are not considered Iranian by virtue of marriage or birth to an Iranian woman.

“Well,” I said, “we were married before my son’s birth, but if you mean our Islamic marriage—”

“No,” she interrupted me, “it’s no problem really, but it seems you were married in 2010, and that was after—”

“No,” I said, my turn to interrupt. “We were married a month

before

he was born.”

“It’s no problem,” she repeated, “but I mean, umm, you were married

after

he was, umm, conceived.” She sounded embarrassed. “Was he adopted?”

“No!” I replied, taken aback by the question. “If he was adopted, we wouldn’t have been identified as his birth parents on his birth certificate, would we?” What I wanted to say to her was that it

is

, perhaps contrary to her beliefs, actually possible for a man and woman to have a child out of wedlock, that conception doesn’t happen only if the man and woman are married, but I bit my tongue. I knew that in the Islamic Republic authorities have to maintain the appearance, at least, that men and women do not—perhaps even

cannot

—have sex before marriage. Just the appearance, mind you, for no one is that naïve in Iran, not even employees of the Islamic state.

“Well,” she said, “it

is

possible to have you listed as the father if you adopted, but it’s no problem. We just ask you to fax us a letter saying that your son is not adopted, and Tehran will be able to issue his birth certificate, and then we can issue a passport.” It seems she still didn’t believe that I was the biological father, perhaps not just because of the premarital sex that may have offended her sensibilities, but also because of my age, which she must have thought far too old. Iranians my age tend to be grandfathers. But there was another element at play, too: this passive-aggressive (and very Persian) behavior in social intercourse really meant that she wanted me to agree and declare, to her and the Iranian bureaucratic world, that my son was conceived out of wedlock.

Gotcha!

Getting citizenship papers for my family was actually much easier while we were still in the United States (or anywhere else outside Iran) than it would have been in Iran, and it had been something I was eager to do, since I was confident that a time would come when I would want to visit Iran with my wife and son. My wife had expressed her desire to travel to Iran with me in the past, when it was a practical impossibility, but now that we were married, her having an Iranian passport meant there would be no obstacles to her accompanying me on one of my trips, with our son if we wanted, even a

trip that came up at the very last minute, as had often happened for me before. Appearances aside, paperwork is something the Iranian bureaucracy, the single largest employer of Iranians, excels in, even in the age of paperless communication and record keeping. “You know,” one Iranian official at the Interests Section, a longtime resident of Washington, mentioned to me when I told him I was sending in my applications, “Tehran won’t return the original American birth certificates of your son or your wife.” When I expressed surprise and was a little hesitant to just hand over these precious documents to the Iranian government, never to be recovered, he said, “Well, America is not like Iran, is it? It’s not like you have to jump through hoops to get a replacement birth certificate—you just ask for one in any U.S. state, and they’ll send it to you!”