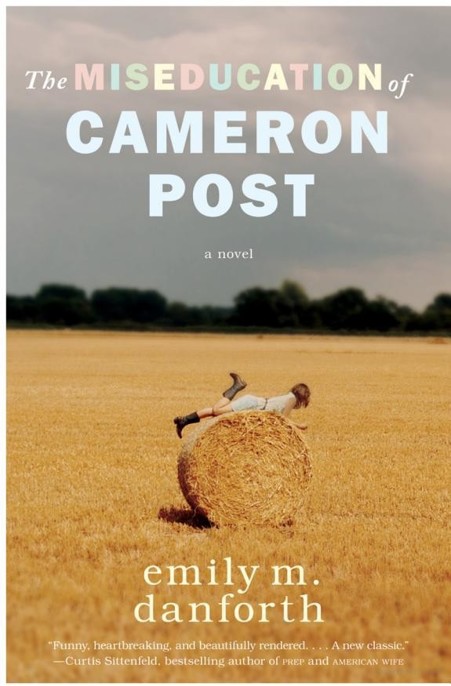

The Miseducation of Cameron Post

Read The Miseducation of Cameron Post Online

Authors: Emily M. Danforth

Tags: #Juvenile Fiction, #Social Issues, #Homosexuality, #Dating & Sex, #Religious, #Christian, #General

THE

MISEDUCATION

OF

CAMERON POST

emily m. danforth

For my parents, Duane and Sylvia Danforth,

who filled our home with books and stories

Contents

Chapter One

Chapter Two

Chapter Three

Chapter Four

Part Two: High School 1991-1992

Chapter Five

Chapter Six

Chapter Seven

Chapter Eight

Chapter Nine

Chapter Ten

Chapter Eleven

Chapter Twelve

Part Three: God’s Promise 1992-1993

Chapter Thirteen

Chapter Fourteen

Chapter Fifteen

Chapter Sixteen

Chapter Seventeen

Chapter Eighteen

Chapter Nineteen

Chapter Twenty

Chapter Twenty-one

T

he afternoon my parents died, I was out shoplifting with Irene Klauson.

Mom and Dad had left for their annual summer camping trip to Quake Lake the day before, and Grandma Post was down from Billings

minding me

, so it only took a little convincing to get her to let me have Irene spend the night. “It’s too hot for shenanigans, Cameron,” Grandma had told me, right after she said yes. “But we gals can still have us a time.”

Miles City had been cooking in the high nineties for days, and it was only the end of June, hot even for eastern Montana. It was the kind of heat where a breeze feels like someone’s venting a dryer out over the town, whipping dust and making the cottonseeds from the big cottonwoods float across a wide blue sky and collect in soft tufts on neighborhood lawns. Irene and I called it summer snow, and sometimes we’d squint into the dry glare and try to catch cotton on our tongues.

My bedroom was the converted attic of our house on Wibaux Street, with peaking rafters and weird angles, and it just baked during the summer. I had a grimy window fan, but all it did was blow in wave after wave of hot air and dust and, every once in a while, early in the morning, the smell of fresh-cut grass.

Irene’s parents had a big cattle ranch out toward Broadus, and even all the way out there—once you turned off MT 59 and it was rutted roads through clumps of gray sagebrush and pink sandstone hills that sizzled and crisped in the sun—the Klausons had central air. Mr. Klauson was that big of a cattle guy. When I stayed at Irene’s house, I woke with the tip of my nose cold to the touch. And they had an ice maker in the door of their fridge, so we had crushed ice in our orange juice and ginger ale, a drink we mixed up all the time and called “cocktail hour.”

My solution to the lack of air conditioning at my own house was to run our T-shirts under the cold, cold tap water in the bathroom sink. Then wring them out. Then soak the shirts again before Irene and I shivered into them, like putting on a new layer of icy, wet skin before we got into bed. Our sleep shirts crusted over during the night, drying and hardening with the hot air and dust like they had been lightly starched, the way Grandma did the collars of my dad’s dress shirts.

By seven that morning it was already in the eighties, and our bangs stuck to our foreheads, our faces red and dented with pillow marks, gray crud in the corners of our eyes. Grandma Post let us have leftover peanut-butter pie for breakfast while she played solitaire, occasionally looking up through her thick glasses at the

Perry Mason

rerun she had on, the volume blasting. Grandma Post loved her detective stories. A little before eleven she drove us to Scanlan Lake in her maroon Chevy Bel Air. Usually I rode my bike to swim team, but Irene didn’t have one in town. We’d left the windows down, but the Bel Air was still all filled up with the kind of heat that can only trap itself in a car. Irene and I fought over shotgun when my mom was driving, or her mom was driving, but when we were riding in the Bel Air, we sat in the backseat and pretended to be in the Grey Poupon commercials, with Grandma as our chauffeur, her tenaciously black hair in a newly set permanent just visible to us over the seat back.

The ride took maybe a minute and a half down Main Street (including the stop sign and two stop lights): past Kip’s Minute Market, which had Wilcoxin’s hardpack ice cream and served scoops almost too big for the cones; past the funeral homes, which stood kitty-corner from one another; through the underpass beneath the train tracks; past the banks where they gave us Dum-Dum Pops when our parents deposited paychecks, the library, the movie theater, a strip of bars, a park—these places the stuff of all small towns, I guess, but they were our places, and back then I liked knowing that.

“Now you come home right after you’re done,” Grandma said, pulling up in front of the blocky cement lifeguard shack and changing rooms that everybody called the bathhouse. “I don’t want you two monkeying around downtown. I’m cuttin’ up a watermelon, and we can have Ritz and cheddar for lunch.”

She

toot-toot

ed at us as she rolled away toward Ben Franklin, where she was planning to buy even more yarn for her ever-expanding crocheting projects. I remember her honking like that, a little

pep-in-her-step

, she would have said, because it was the last time for a long time that I saw her in just that sort of mood.

“Your grandma is crazy,” Irene told me, extending the word

crazy

and rolling her heavy brown eyes.

“How’s she crazy?” I asked, but I didn’t let her answer. “You don’t seem to mind her when she’s giving you pie for breakfast. Two pieces.”

“That still doesn’t mean she’s not a nutter,” Irene said, yanking hard on one end of the beach towel I had snaked over my shoulders. It slapped against my bare legs before thwacking the concrete.

“Two pieces,” I said again, gripping the towel, Irene laughing. “Second-helping Sally.”

Irene kept on giggling, dancing away from my reach. “She’s completely crazy, totally, totally nuts—mental-patient nuts.”

This is how things usually went with Irene and me. It was best friends or sworn enemies with no filler in between. We tied for top grades in first through sixth. On the Presidential Fitness Tests she beat me at chin-ups and the long jump and I killed her on push-ups, sit-ups, and the fifty-yard dash. She’d win the spelling bee. I’d win the science fair.

Irene once dared me to dive from the old Milwaukee Railroad bridge. I did, and split my head against a car engine sunk into the black mud of the river. Fourteen stitches—the big ones. I dared her to saw down the yield sign on Strevell Avenue, one of the last street signs in town with a wooden base. She did. Then she had to let me keep it, because there was no way of getting it back to her ranch.

“My grandma’s just old,” I said, circling my wrist and lassoing the towel down by my feet. I was trying to twist it thick enough to use it as a whip, but Irene had that figured out.

She jumped backward, away from me, colliding with a just-finished swim-lesson kid still wearing his goggles. She partially lost a flip-flop in the process. It slid forward and hung from a couple of toes. “Sorry,” she said, not looking at the dripping kid or his mom but kicking the flip-flop ahead of her so she could stay out of my reach.

“You girls need to watch out for these little guys,” the mom told me, because I was closest to her and I had a towel-whip dangling, and because it was always me who got the talking-to when it came to Irene and me. Then the mom grabbed the goggle boy’s hand as though he was seriously hurt. “You shouldn’t be playing around in the parking lot anyway,” she said, and pulled her son away, walking faster than his little sandaled feet could quite keep up.

I put the towel back around my shoulders and Irene came over to me, both of us watching the mom load swim-lesson kid into their minivan. “She’s nasty,” Irene said. “You should run over and pretend to get hit by her car when she backs up.”

“But do you dare me to?” I asked her, and Irene, for once, didn’t have anything to say. And even though I was the one who said it, once the words were out there, between us, I was embarrassed too, unsure of what I should say next, both of us remembering what we’d done the day before, right after my parents had left for Quake Lake, this thing that had been buzzing between us all morning, neither of us saying a word about it.

Irene had dared me to kiss her. We were out at the ranch, up in the hayloft, sweaty from helping Mr. Klauson mend a fence, and we were sharing a bottle of root beer. We’d spent the better part of the day trying to one-up each other: Irene spit farther than I could, so I jumped from the loft into the hay below, so she did a flip off a stack of crates, so I did a forty-five-second handstand with my T-shirt all bunched down over my face and shoulders and the top half of me naked. My roller-rink necklace—both of us wore them, half of a heart each, with our initials—dangled across my face, a cheap-metal itch. Those necklaces left green marks around our necks where they rubbed, but our tans mostly covered them up.

My handstand would have lasted longer if Irene hadn’t poked at my belly button, hard.

“Knock it off,” I managed, before crumpling over on top of her.

She laughed. “You’re all pasty white where your swimsuit covers you up,” she said, her head close to mine and her mouth huge and hollow, and begging for me to stuff hay into it, so I did.

Irene coughed and spit for a good thirty seconds, always dramatic. She had to pluck a couple of pieces out of her braces, which had new purple and pink bands on them. Then she sat up straight, all business. “Show me your swimsuit lines again,” she said.

“Why?” I asked, even though I was already stretching my shirt to show her the bright stripe of white that fell between the dark skin on my neck and my shoulder.

“It looks like a bra strap,” she said, and slowly ran her pointer finger along the stripe. It made my arms and legs goose-bump. Irene looked at me and grinned. “Are you gonna wear a bra this year?”

“Probably,” I told her, even though she had just seen firsthand how little need I had for one. “Are you?”

“Yeah,” she said, retracing the line, “it’s junior high.”

“It’s not like they check you at the door,” I said, liking the feel of that finger but afraid of what it meant. I grabbed another handful of hay and stuffed this one down the front of her T-shirt, a purple one from Jump Rope for Life. She shrieked and attempted retaliation, which lasted only a few minutes, both of us sweating and weakened by the thick heat that filled the loft.

We leaned up against the crates and passed the now-warm root beer back and forth. “But we are supposed to be older,” Irene said. “I mean, to act older. It is junior high school.” Then she took a long swallow, her seriousness reminding me of an after-school special.