The Missing

the Missing

the Missing

BEVERLY

LEWIS

The Missing

Copyright © 2009

Beverly M. Lewis

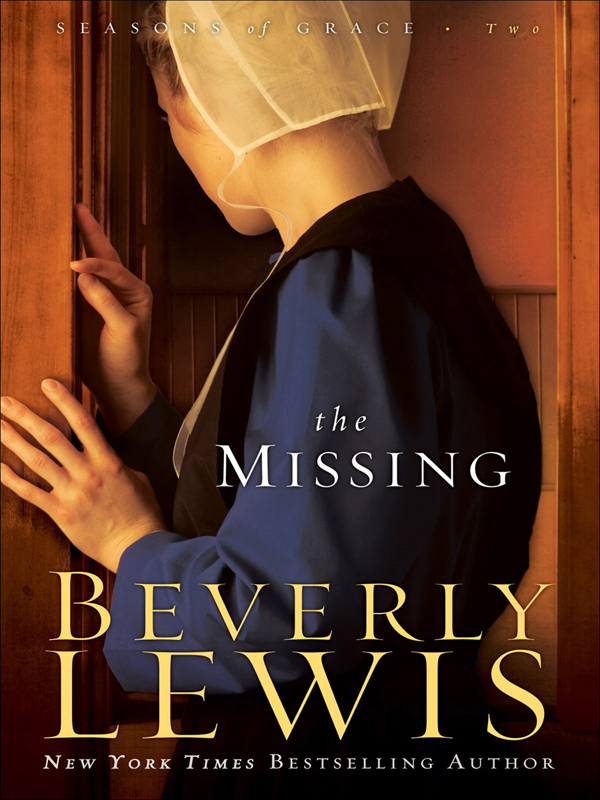

Art direction by Paul Higdon

Cover design by Dan Thornberg, Design Source Creative Service

Cover doorframe image courtesy of Scott County Historical, Historic Stans House

Scripture quotations are from the King James Version of the Bible.

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means—electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise—without the prior written permission of the publisher. The only exception is brief quotations in printed reviews.

Published by Bethany House Publishers

11400 Hampshire Avenue South

Bloomington, Minnesota 55438

Bethany House Publishers is a division of

Baker Publishing Group, Grand Rapids, Michigan.

E-book edition created 2009

ISBN 978-1-4412-1042-5

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data is on file at the Library of Congress, Washington, DC.

To

Virginia Campbell,

whose generosity and dedication

to the Pikes Peak branch

of

The National League of American Pen Women

are a joyful inspiration to me.

By Beverly Lewis

ABRAM’S DAUGHTERS

The Covenant • The Betrayal • The Sacrifice

The Prodigal • The Revelation

THE HERITAGE OF LANCASTER COUNTY

The Shunning • The Confession • The Reckoning

ANNIE’S PEOPLE

The Preacher’s Daughter • The Englisher • The Brethren

THE COURTSHIP OF NELLIE FISHER

The Parting • The Forbidden • The Longing

SEASONS OF GRACE

The Secret • The Missing

The Postcard • The Crossroad

The Redemption of Sarah Cain

October Song • Sanctuary

*

• The Sunroom

The Beverly Lewis Amish Heritage Cookbook

*

with David Lewis

BEVERLY LEWIS, born in the heart of Pennsylvania Dutch country, is

The New York Times

bestselling author of more than eighty books. Her stories have been published in nine languages worldwide. A keen interest in her mother’s Plain heritage has inspired Beverly to write many Amish-related novels, beginning with

The Shunning

, which has sold more than one million copies.

The Brethren

was honored with a 2007 Christy Award.

Beverly lives with her husband, David, in Colorado.

CONTENTS

I

stumbled upon my mother’s handkerchief in the cornfield early this morning. Halfway down the row I spotted it—white but soiled, cast in the mire of recent rains. Only one side of the stitched hem was visible, the letter

L

poking out from the furrow as if to get my attention. I stared at it . . . all the emotions of the past three weeks threatening to rise up and choke me right then and there.

Leaning over, I clutched the mud-caked hankie in my hand. Then, tilting my head up, I looked toward the eastern sky, to the freshness of this new day.

Twice now, I’ve walked the field where Mamma sometimes wandered late at night—weeks before she ever left home. Like our sheep, she’d followed the same trails till ruts developed. I couldn’t help wondering where the well-trod path had led her by the light of the lonely moon. Honestly, though, ’tis only in the daylight that I’ve been compelled to go there, drawn by thoughts of her and the hope of some further word, whenever that might come.

I shook the dirt off the hankie and traced the outline of the embroidered initial—white on white. So simple yet ever so pretty.

My hand lingered there as tears slipped down my cheeks.

“Mamma . . . where

are

you?” I whispered to the breeze. “What things don’t we know?”

Later, when breakfast preparations were well under way, my younger sister, Mandy, headed upstairs to redd up what had always been our parents’ room. The solitary space where

Dat

still slept.

Still shaken at finding Mamma’s hankie, I wandered across the kitchen and pushed open the screen door. I leaned on it and stared toward the shining green field, with its rows as straight as the telephone poles up the road, near Route 340. Near where the fancy folk live.

I reached beneath my long work apron and touched the soiled handkerchief in my dress pocket.

Mamma’s very own.

Had I unknowingly yearned for such a token? Something tangible to cling to?

With a sigh, I hurried through the center hallway and up the stairs. Various things pointed to Mamma’s long-ago first beau as a possible reason for her leaving. But I had decided that no matter how suspicious things looked, I would continue to believe Mamma was true to Dat.

I stepped into our parents’ large bedroom, with its gleaming floorboards and hand-built dresser and blanket chest at the foot of the bed. “I want you to see something, Mandy,” I said.

My sister gripped the footboard.

“Jah?”

I pushed my hand into my pocket, past Mamma’s hankie, and found the slip of paper. “Just so ya know, I’ve already shown this to Dat.” I drew a slow breath. “I don’t want to upset you, but I have an address in Ohio . . . where Mamma might be stayin’.”

I showed her what our grandmother had given me.

“What on earth?”

I told her as gently as I could that I’d happened upon a letter

Dawdi

Jakob had written when Mamma was young—when she and our grandmother had gone west to help a sickly relative.

“Why do you and

Mammi

think she might’ve gone there?”

Mandy’s brown eyes were as wide as blanket buttons.

“Just a hunch.” Really, though, I hadn’t the slightest inkling what Mamma was thinking, going anywhere at all. Let alone with some of Samuel Graber’s poetry books in tow. “I hope to know for a fact soon enough,” I added.

She stared in disbelief. “How?”

“Simple. I’m goin’ to call this inn.”

Mandy reached for the paper, holding it in her now trembling hand. “Oh, Grace . . . you really think she might be there?”

Suddenly it felt easier to breathe. “Would save me tryin’ to get someone to make a trip with me to find out.” I bit my lip.

“And Dat says I have to . . . or I can’t go at all.”

“You can’t blame him for that.” Mandy sighed loudly. Then she began to shake her head repeatedly, frowning to beat the band.

I touched her shoulder. “What is it, sister?”

She shrugged, remaining silent.

“What, Mandy?”

“It’s just so awful dangerous . . . out in the modern, fancy world.”

“Aw, sister . . .” I reached for her. “Mamma can take care of herself. We must trust that.”

She nodded slowly, brown eyes gleaming with tears. Then, just as quickly, she wiped her eyes and face with her apron.

She shook her head again. “

Nee—

no, we must trust the

Lord

to watch over her.”

With a smile, I agreed.

Mandy leaned her head against my cheek. “I hope you won’t up and leave us, too. I couldn’t bear it, Gracie.” She stepped back and looked at me with pleading eyes. “And if ya do get Mamma on the phone, please say how much I miss her. How much we

all

do.” Mandy looked happier at the prospect. “That we want her to come home.”

I squeezed her plump elbow, recalling the way Dat’s eyes had lit up when I showed him the address early this morning. The way he’d turned toward the kitchen window, a faraway glint in his eyes as he looked at the two-story martin birdhouse—just a-staring. I’d wondered if he was afraid to get his hopes up too high. Or was there more to this than any of us knew?

But this wasn’t the time to dwell on such things. I needed to think through what I might say to whoever answered the phone.

How to make it clear who I was . . . and why I was calling.

Mandy went around the bed and reached for the upper sheet, pulling it taut. Next, the blanket. She gave me a sad little smile, and after we finished Dat’s room, she said no more as she headed downstairs to scramble the breakfast eggs.

I made my way to my own bedroom, down the hall. There, I took Mamma’s mud-stained hankie from my pocket.

Will you

even come to the phone . . . when you find out who’s calling?

Then, as carefully as if it were a wee babe, I placed the handkerchief in my dresser drawer with a prayer in my heart.

Grant me the courage, Lord.

For everything you have missed,

you have gained something else. . . .

—Emerson

A

dah Esh slipped from her warm bed, having slept longer than usual. In the quiet, she tiptoed to the end of the hall to the spare room designated as a sewing room. The cozy spot on the second floor had two northeast-facing windows. Adah raised the dark green shade and stood there, looking out at the unobstructed expanse of space and sky. Tendrils of yellow had already sprung forth like a great fan below the horizon.

Since Lettie’s leaving nearly a month ago, Adah felt compelled to come here and offer up the day and its blessings to God. She’d first observed this act of surrender in Lettie herself, who as a teenager had begun the day at her bedroom window, her shoulders sometimes heaving with the secret she bore. Other times Adah would find her scooted up close to the glass as she looked out, as if yearning for comfort in the glory of the dawn.

On days when her daughter found the wherewithal to speak, Lettie might point out the sun’s light glinting on the neighbors’ windmill across the field.

“It’s like a gift,”

she’d say, seemingly grasping for even the slightest hint of beauty. Anything to momentarily take her attention away from her grief. Her shame.

Adah’s heart ached anew at the old pain of discovering her young Lettie with child, and by the young man she and Jakob had so disliked. Poor Lettie, distraught beyond Adah’s or anyone’s ability to cheer her. . . . Her heartsick girl had wept at her window like a trapped little sparrow in a cage.

But until recently, those dark and sad days had seemed long past. No more did Adah despise Samuel Graber for wounding her daughter so, nor did she hold resentment against Lettie for her infatuation with him . . . or their dire sin. And never had she forgotten the infant she’d made Lettie give up—her own tiny grandbaby—nor the adoption arrangements made afterward.

Now Adah rested her hand on the sill of the window on this side of son-in-law Judah’s big three-story house. She committed the day to almighty God, who’d made it. The One who knew and saw Lettie, too, wherever she might be.

The view from this particular window suited Adah just fine, different though it was from that outside of Jakob’s and her first home. In recent years ownership of that house had been transferred to their youngest married son and his wife—Ethan and Hannah. As for herself, Adah was content to live out her sunset years here, under Lettie’s husband’s watch-care.

If only

Lettie might be here, too. O Lord, may it be so!