The Modern Middle East (10 page)

Read The Modern Middle East Online

Authors: Mehran Kamrava

Tags: #Politics & Social Sciences, #Politics & Government, #International & World Politics, #Middle Eastern, #Religion & Spirituality, #History, #Middle East, #General, #Political Science, #Religion, #Islam

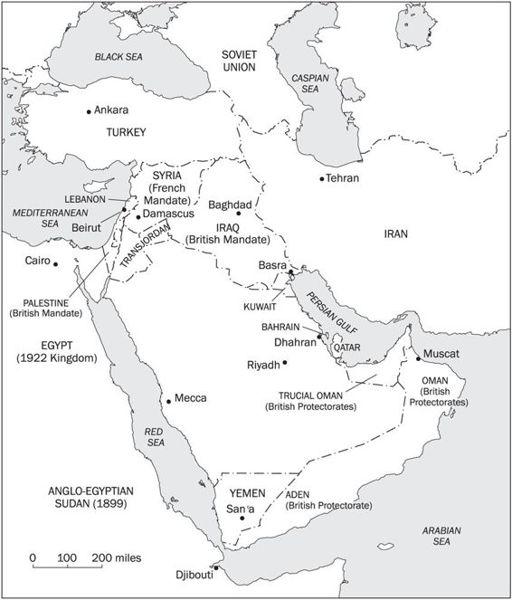

Map 3.

French and British mandates after World War I

The creation of Transjordan was also a thoroughly colonial endeavor, this time by Britain. Under Ottoman rule, the historic boundaries of Palestine had never been clearly delineated, and the area was at times viewed as part of “southern Syria.” More commonly, Palestine was seen as the area bordering the Mediterranean on the west, Syria on the north, and the Hijaz on the east. But under British mandatory rule after 1920, the sparsely populated desert area east of the Jordan River gained increasing autonomy, and it was here that Churchill convinced Abdullah, Faisal’s older brother, to abandon his Syrian campaign and become the ruler of the newly created Transjordan. By the time the League of Nations formally recognized the British mandate of Palestine in 1922, the area in question had already been partitioned into two, with Palestine west of the Jordan River and Transjordan on the east, and the Hashemites were in control of the latter.

27

A 1928 agreement between the British government and Abdullah, who had now adopted the royal title of emir, gave Transjordan its own government, with British tutelage over foreign policy and finance. A succession of British military officers, the most famous of whom was Glubb Pasha, were put in charge of organizing and commanding the new country’s army, the Arab Legion.

Egypt’s story at this juncture is somewhat different, although, like that of its neighbors, it is still replete with colonial intervention. In July 1882 Britain had invaded Egypt, which had long been an autonomous province within the Ottoman Empire, to protect its access to the Suez Canal, whose construction had lasted from 1854 to 1869. Throughout the First World War and for decades thereafter, safe and ready access to the Suez remained Britain’s paramount goal.

28

This concern prompted British control over Egypt to be near complete. While retaining the autonomous Ottoman governor (the khedive) in office, Britain controlled the Egyptian army and the ministries. The dominant political figure in Egypt, in fact, was not the khedive but rather the British consul-general.

29

By the war’s end, however, rebellions in the Sudan (then part of Egypt) and serious anti-British riots in Egypt in 1919 had made overt British control of Egyptian affairs

extremely costly. Weighing options that ranged from more extensive domination to conditional independence, Britain finally opted for the latter and, on February 28, 1921, unilaterally declared Egypt independent. But neither the control of the Suez nor the larger imperial interests of Britain were totally abandoned. Thus independence came with four conditions: control of the Suez and other British interests; control over Egyptian foreign policy and defense; control over the Sudan; and the right to protect foreign interests and religious minorities. Of all the former Ottoman provinces, Egypt was one of the first to become independent. But the extent and essence of this independence were far from complete.

In the Maghreb, meanwhile, the French remained firmly entrenched, having invaded and conquered Algeria in 1830, Tunisia in 1881, and Morocco in 1912. For some time, French merchants in Marseilles had retained commercial ties with the Maghreb, even after Libya, Tunisia, and Algeria had fallen under Ottoman suzerainty in the mid-to late 1500s. Initially, in all three of its Maghrebi provinces, Ottoman rule followed the pattern practiced elsewhere in the empire: an Istanbul-appointed governor, assisted by a corps of professional janissaries, a religious judge (

qadi

), and a navy, used primarily for privateering and harassment of commercial European ships in the Mediterranean.

30

But this was not to last long, as local governors soon started paying only lip service to Istanbul and exercising considerable autonomy and independence. Given the geographic distance from the Ottomans’ Anatolian heartland and the Porte’s own internal difficulties, Istanbul was hardly in a position to impose its imperial authority on its Maghrebi possessions. By the middle of the seventeenth century, with their local rulers enriched by the revenues accrued through piracy and the sale of captured ship crews as slaves, Tunisia, Algeria, and Libya had become all but independent from Istanbul.

Morocco, for its part, was geographically too remote and isolated to have become subject to Ottoman rule. Despite the Porte’s initial efforts at conquest, Morocco developed an indigenous, tradition-bound system of religio-political rule of its own. From the 1550s until the 1830s, the country was ruled by a series of sherifian monarchs claiming to be descendants of the Prophet Muhammad (i.e., sherifs), belonging first to the Saadian and then to the Alawite dynasties. The sherifians made impressive headway in uniting the country and imposing central government authority throughout the territories. Nevertheless, on entering the twentieth century, in some respects Morocco remained divided into two parts. The Bilad al-Makhzan (government’s place) was located along the north and northwest coast, was populated by Arabic speakers, and eventually became subject to

the official jurisdiction of the central government. The Bilad al-Siba, in the interior mountains and desert areas, was populated mostly by Berbers and remained largely outside central government control.

31

The significance of Morocco’s division into the Bilad al-Makhzan and the Bilad al-Siba is a matter of some debate, with some scholars considering it a defining feature of the country’s colonial period and others seeing it as more of a divide deliberately perpetuated for purposes of colonial administrative convenience.

32

But there is no doubt that the sultan’s power was geographically circumscribed and often contested.

Lack of preexisting central authority made it harder for the French to dominate the Maghreb. It took them nearly twenty years, for example, to pacify Morocco, and from 1921 to 1926 they were forced to fight a protracted war in the northern mountains of Rif. At its peak, some seven hundred thousand French and Spanish troops took part in what came to be known as the Rif War. Eventually, however, French colonial designs brought the whole of the Maghreb under direct French rule, with the exception of Libya, which fell prey to an Italian invasion in 1911. Unlike the British, who went into the Middle East to defend their imperial interests in the Indian subcontinent, the French went into North Africa with less clear strategic goals and interests. The French invasion of Algeria in 1830 appears to have been motivated primarily by domestic political considerations; competition with Britain seems to have been only a secondary concern. And when the French did conquer the Maghreb, they were initially and briefly undecided about what to do with their new acquisitions. Then Algeria was targeted for assimilation and treated as yet another French province—assuming, of course, that the Bureau of Native Affairs could make civilized Frenchmen out of the natives. Thus the colonial authorities actively promoted Algeria’s rapid colonization, and before long an expanding and relatively affluent community of

colons,

with significant landholdings, emerged. Tunisia and later Morocco became protectorates, both used for their rich minerals and their farms, and, most importantly, for the protection of the newly acquired province. Consequently, French colonial rule was less direct than British rule, and some of the preexisting local institutions of judicial administration were allowed to exist side by side with colonial administrative organs.

Both British and French colonial authorities often contemptuously viewed the native population over whom they ruled as uncivilized. The French, additionally, frequently used violence and systematic mistreatment of the locals as part of their colonial policy, especially in Algeria. An 1833

report by a French parliamentary commission looking into the fall of Algeria is revealing:

Figure 2.

Women in Algiers in the 1880s. Corbis.

We have sent to their deaths on simple suspicion and without trial people whose guilt was always doubtful and then despoiled their heirs. We massacred people carrying [our] safe conduct, slaughtered on suspicion entire populations subsequently found to be innocent; we have put on trial men considered saints by the country, men revered because they had enough courage to expose themselves to our fury so that they could intervene on behalf of their unfortunate compatriots; judges were found to condemn them and civilized men to execute them. We have thrown into prison chiefs of tribes for offering hospitality to our deserters; we have rewarded treason in the name of negotiation, and termed diplomatic action odious acts of entrapment.

33

Despite its chilling findings, the report led to few changes in the conduct of French policy in Algeria and even fewer changes in Tunisia and Morocco. Gradually, the political violence unleashed on the local populations was institutionalized, and all threats to colonial rule or the privileged position of the

colons

were harshly suppressed.

34

This was to have important

consequences later for the manner and processes through which Maghrebi independence was won.

Not to be left behind in the Anglo-French grab for territories in the Middle East and North Africa, in October 1911, Italian military forces invaded the Ottomans’ other province in the Maghreb, Libya. Italian colonialism was motivated by two primary concerns: maintaining the appearance of a great-power status and alleviating some of the demographic pressures stemming from the country’s burgeoning population.

35

The Ottoman hold on Libya, like that on Algeria and Tunisia, had never been very firm, and, like Morocco, Libya entered the twentieth century ridden with tribal conflicts and lacking strong central authority. There was also an increasingly powerful Sufi order called the Sanusi, after its original founder, Muhammad al-Sanusi, who advocated reforming Islam, modeling it after the Islam practiced by the Prophet in Medina, and strongly opposed European colonialism. Libya’s colonization by Italians had started as early as the late 1880s and was strongly supported by Italian industrialists, nationalists, and the Catholic Church.

36

When colonization met unexpectedly stiff resistance by the Sanusi and the local tribes, the Italian government was forced to agree to limited self-rule and autonomy between 1914 and 1922. The policy was soon reversed by Rome’s fascist government, which viewed Libya as the “fourth shore” of fascist ideology and its conquest as an important step in resurrecting the Roman Empire in Africa. But Italy’s conquest of Libya was not completed until 1932. Large agricultural companies supervised the large-scale immigration of poor Italian peasants from the south into Libya. By the early 1940s, out of a population of one million Libyans, some one hundred thousand were Italians. As fortune would have it, the outbreak of World War II brought Italy’s imperial ambitions to an end.

Such was the shape of the Middle East and North Africa at the end of World War I. The Ottomans were destroyed and were succeeded by a republican system in Turkey. Britain and France became the region’s dominant powers, each having mandates of its own: Palestine and Iraq for Britain, Syria and Lebanon for France. Egypt and the Emirate of Transjordan existed in a state of precarious independence, with Britain remaining the true master of their destinies. The Maghreb had already fallen to the French in the closing decades of the 1800s, and Libya was under Italian control in 1911. Finally, Iran and the Kingdom of Hijaz clung to an independence of sorts. Like Egypt, however, neither could assert complete sovereignty over its territory without British support. Whatever independence had come to the Middle East had done so haltingly, and it was yet to be fully played out in the chaotic decades of the 1930s and 1940s.

THE TURBULENT 1930S AND 1940S