The Modern Middle East (30 page)

Read The Modern Middle East Online

Authors: Mehran Kamrava

Tags: #Politics & Social Sciences, #Politics & Government, #International & World Politics, #Middle Eastern, #Religion & Spirituality, #History, #Middle East, #General, #Political Science, #Religion, #Islam

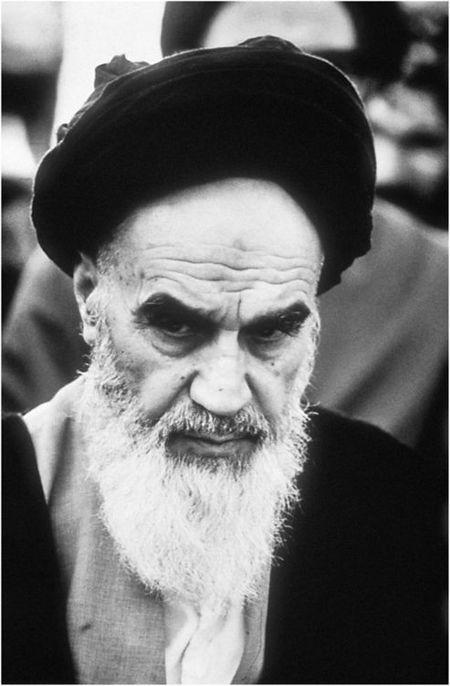

Figure 11.

Ayatollah Khomeini, leader of Iran’s Islamic revolution. Corbis.

IRAN’S THREE REPUBLICS

Following the collapse of the monarchy, it was natural for Iranian revolutionaries to want to establish a republic, which, in the popular psyche at least, was seen as synonymous with democracy. That the new system would be republican was certain; the controversy revolved around the precise type of republic to be adopted. The emergence of Islam as the primary vehicle for the revolution made it almost inevitable that religion would play a role in the postrevolutionary system. The heightened religious sensibilities of Iranians because of the revolutionary odyssey also made the postrevolutionary marriage of religion and politics not only palatable but desirable. But the revolution had not started out as singularly religious, and it did have early inheritors who wanted to reap its benefits in a secular environment. In any event, Ayatollah Khomeini, who had now emerged as the undisputed “Imam” of millions of Iranians, prevailed, seeing to it that the incoming republic was in every way “Islamic.” On March 30 and 31, 1979, a historic referendum was held in which Iranians were asked to answer a simple question: “Should Iran be an Islamic republic?” Some 98.2 percent of the more than twenty million ballots cast answered in the affirmative. The Islamic Republic of Iran was therefore established.

The Islamic Republic has had three phases, or, more aptly, it has really been three republics. The First, Second, and Third Republics roughly correspond, respectively, to the eras of postrevolutionary consolidation, construction, and factional infighting. The First Republic lasted from its inception in 1979 until the conclusion of Iran’s war with its neighbor Iraq in July 1988. This was by far the most radical phase in the evolution of the postrevolutionary system. Domestically, the First Republic witnessed the steady and often ruthless narrowing of political space brought on by the elimination of the “revolution’s enemies,” many of whom had once been Khomeini’s close collaborators. Internationally, the Islamic Republic shocked the world and incurred isolation and condemnation by holding U.S. diplomats hostage for 444 days and refusing to accept repeated cease-fire offers from Baghdad until 1988.

The Second Republic, by contrast, was one of reconstruction and relative moderation. Ayatollah Khomeini’s death in June 1989 gave greater maneuverability to revolutionaries who were eager to open Iran to the outside world and to give substance to their vision of a modern Islamic state. The Second Republic lasted only eight years, however, and in 1997 was replaced by the Third Republic, one in which deep fissures within the ruling elite became apparent. By its very nature the Third Republic is bound to be impermanent as it features profound disagreements at the highest levels of

the system over the ideological underpinnings of the Islamic Republic state and its relations with society. Only time will tell what ultimate shape the state will take, and what the outcome will be of the evolution of Iran’s revolution.

The First Republic got off to a rocky start. During this time, the postrevolutionary leadership consolidated itself forcefully and brutally, eliminating rivals one by one and, in the process, giving shape to its vision of the new social, political, and economic orders. In this phase, the revolution’s victors set out to institutionalize their powers, a task in which they succeeded on a variety of fronts, ranging from creating a political party to dominating the Majles, then the presidency, and eventually, through extensive purges, the bureaucracy and the military. Whoever disagreed or refused to toe the “Imam’s line” was accused of being a “counter-revolutionary,” a “monarchist,” a lackey of “the Great Satan,” or, worse yet, a “hypocrite” (

munafiq

). The regime that emerged was highly authoritarian, a self-appointed guardian of Islam and public morality, and, as it turned out, highly resilient. Initially, most of its opponents were not easily brushed aside or suppressed, and the regime suffered some truly devastating blows resulting from the assassination of some of its highest-ranking leaders. But Khomeini and his increasingly small inner circle persevered through it all and, at the expense of many former comrades, eventually prevailed. The First Republic was clearly built on and sustained by a reign of terror.

The postrevolutionary experience had started out very differently in the days and weeks immediately following the monarchy’s collapse. The demise of Pahlavi authoritarianism unleashed popular energies that had been pent up since the early 1950s. The initial absence of effective central authority ushered in a temporary era of anarchy and lawlessness. Most institutions of the state had already collapsed or were about to collapse, and new ones had not yet emerged to replace them. Thus many people took the law into their own hands, emboldened by the estimated three hundred thousand weapons they had acquired in the monarchy’s final days.

45

The revolutionary government’s repeated pleas to people to turn in their weapons met with little success. In the Revolutionary Committees, called the Komiteh, that sprang up in all neighborhoods and districts, young men with little previous experience gave themselves responsibilities for traffic control, policing, arresting monarchists, fighting other “counter-revolutionaries,” and enforcing the revolution’s new morality. The provisional government, to which Khomeini had appointed the longtime National Front activist Mehdi Bazargan, was too moderate in temperament and disposition to cope with the revolutionary tempo of the times. Bazargan’s cabinet could not even

stop the summary justice being meted out by the Revolutionary Courts, as a result of which some sixty-eight people were executed after speedy “revolutionary trials.”

46

The fate of Bazargan’s cabinet ended up being decided in the streets. Daily street demonstrations had become a fact of life, with each faction in the revolutionary struggle taking its cause to the streets to express itself and to impress others with its show of strength. Real power lay in the streets, and increasingly, thanks to the efforts of club-wielding ruffians calling themselves members of the Party of God, the Hezbollahis, the street listened only to Khomeini. Passions remained too inflamed and the excitement of the revolution too fresh for the country’s political rhythm to assume any semblance of normalcy. But the stakes were too high for Khomeini to let control slip away now, and he had to ensure that he remained the revolution’s undisputed leader.

Meanwhile, the deposed shah and his royal entourage were flying from one host country to another in a desperate effort to find a suitable place of exile. Upon leaving Iran, the royals spent some time in Morocco but were encouraged to move on when King Hassan, who had his own domestic difficulties, grew concerned about hosting a deposed monarch. There had always been influential Americans who thought it shameful for the United States not to stand by its old friend in difficult times. Many, in fact, started pressing the Carter administration to allow the shah into the United States to receive medical treatment for his recently disclosed cancer. But the Carter administration had viewed the ensuing diplomatic fallout and the potential dangers to American citizens in Iran as too great to allow the shah’s entry into the United States.

47

Nevertheless, the shah’s friends, chief among them former secretary of state Henry Kissinger and the influential David Rockefeller, were relentless. From Morocco the shah moved to the Bahamas but eventually had to relocate when his security and privacy there could no longer be guaranteed.

48

Next came Mexico, where the shah spent most of summer 1979, as his friends pressured Washington to let the dying ex-king receive medical care in a New York hospital. They finally succeeded, and on October 23 the shah was allowed to travel to New York, where he was operated on at New York Hospital the next day. All along, the Carter administration was worried about the reaction of both the revolutionary government and the excited masses in Tehran. These fears turned out to be justified.

Two weeks after the shah’s arrival in New York, on November 4, one of the street demonstrations in Tehran took an unexpected turn. Mindful of the CIA’s role in installing the shah back in power in 1953, some of the

demonstrators scaled the walls of the U.S. embassy and took its staff hostage. Everyone—from U.S. policy makers in Washington to members of Bazargan’s cabinet, the hostages, and even the attackers themselves—expected the whole episode to last no more than a day or two. A similar event had occurred the preceding February, and the Iranian authorities had quickly reined in the demonstrators and given assurances of increased security for the U.S. embassy and its staff. This time, however, the takeover was to last 444 days.

Following the embassy takeover, the shah left New York for a military base in Texas, where he recuperated, and from there went to Panama, where rumors circulated about his impending arrest and extradition to Iran. He found himself on the move again in March 1980, this time to Egypt, as the guest of his old friend President Sadat. He died there on July 27.

Two days after the embassy takeover started, on November 6, Bazargan’s frustration with the course the revolution was taking and his anger at the imprisonment of American diplomats prompted him to resign from office. Several political dynamics that fundamentally influenced later events were now set in motion. Bazargan’s resignation turned out to be the beginning of a long process whereby Khomeini steadily eliminated one “moderate” revolutionary after another. With the cabinet having resigned, Khomeini transferred power to the secretive Revolutionary Council, one of whose responsibilities was to prepare for elections to an Assembly of Experts. It was up to the assembly to draft a constitution. Not surprisingly, it was packed with members of the Islamic Republic Party (IRP), a cleric-dominated party supportive of Khomeini and claiming allegiance to “the Imam’s line.” The constitution that the assembly produced sanctified Khomeini’s position as the Leader (

velayat faqih

). As its Article 5 stipulated, “The governance of the nation devolves upon the just and pious Faqih who is acquainted with the circumstances of his age; courageous, resourceful, and possessed of administrative ability; and recognized and accepted as leader by the majority of the people.”

49

Presidential elections were held in January 1980, resulting in the landslide victory of Abol Hassan Bani-Sadr, who had been popular in the heady days since the monarchy’s collapse and was a close associate of Khomeini. But Bani-Sadr’s presidency was also ill-fated. His eventual break with Khomeini came on June 21, 1981, when he went into hiding to avoid arrest and eventually escaped to France.

Khomeini’s handling of what evolved into the “hostage crisis” was representative of his modus operandi as a shrewd, populist political animal. Every time events of this nature happened—and in revolutionary Iran they happened a lot—he would initially sit back and gauge the popular response,

then opt for the most “revolutionary” (i.e., radical) option. This is precisely what he did in response to the takeover of the U.S. embassy in Tehran by “Students Following the Imam’s Path.” His role in the progressive purging of his once-close revolutionary collaborators followed a similar pattern, as did his response to Iran’s invasion by Iraq, his

fatwa

on the British author Salman Rushdie, and countless other political maneuvers unknown to outside observers. There are some indications that the takeover of the U.S. embassy might not have been as spontaneous as it initially appeared, although no one suspected that it would drag on as long as it did.

50

But it did serve an important political function for Khomeini and his supporters in the IRP. It helped consolidate the ayatollah’s near-absolute hold over the postrevolutionary polity and enabled him to eliminate more of his rivals.

Meanwhile, the hostage drama inside the embassy compound had given rise to a flurry of frantic efforts by officials in both Washington and Tehran to bring the saga to an early end. As the days turned into weeks and the weeks turned into months, the United States on several occasions discovered that the Iranians did not speak with one voice. The moderate elements were being cast aside one after another, and those who remained, such as Bani-Sadr, could not deliver on the promises they kept making. The Soviet Union’s invasion of Afghanistan in late December 1979 only complicated an already volatile regional climate. The United States pursued multiple tracks and explored a variety of options, some of which were outside normal diplomatic channels.

51

Several times it appeared that a deal was imminent and that the hostages would be released soon, but then the delicate negotiations would be denounced by Khomeini and things would fall apart. But President Carter was doggedly determined to secure the hostages’ release, and toward this goal he was willing to explore all options, including military ones. In fact, on April 24, 1980, an elite American commando unit made up of eight helicopters set out from the warship USS

Nimitz

in the Persian Gulf on a daring and complex mission to attack the embassy compound in Tehran and release the hostages. The mission had been secretly planned for months. But two of the helicopters soon developed mechanical problems in the Iranian desert, and, in the process of abandoning the mission and returning to base, a U.S. transport plane and a helicopter collided on the ground and eight American servicemen were killed.

52

The failed rescue mission gave Khomeini cause for keeping the hostages even longer.