The Monks of War (12 page)

When the Estates met at Paris only a few weeks after Poitiers they were in an angry mood. They demanded a complete reform of the administration, economies to reduce taxation and the dismissal of royal advisers, and insisted that the Dauphin must submit to the direction of a standing council of knights, clergy and bourgeois. The bourgeois had a formidable leader in Etienne Marcel, a rich cloth-dealer who was Provost of the Merchants (the nearest thing to a Lord Mayor of Paris). What made them more dangerous was that they were allied with Navarre’s followers, who wanted their unsavoury King to be Regent. Gradually the Dauphin lost control of the situation. Navarre escaped from prison at the end of 1357 and came to Paris where he forced the Dauphin to pardon him. The King of Navarre addressed an assembly on the subject of his wrongs : ‘His language was so pleasant that he was greatly praised and so little by little he entered into the favour of them of Paris, so that he was better beloved there than the Regent [i.e. the Dauphin].’ However, Navarre shrewdly refused to stay in the capital where Marcel’s party grew more obstreperous every day. In February 1358 they broke into the Dauphin’s chamber to murder the Marshals of Champagne and Normandy, ‘so near him that his clothes were all bloody with their blood and he himself in great peril’. The mob also made him put on a red and blue bonnet—the colours of Paris.

In May 1358 came the

jacquerie.

Unlike the lords in their castles or the bourgeois in their walled towns, the peasants had been unable to defend themselves from the English. During the day they only dared work in the fields if there was a lookout in the church tower to warn them of approaching troops; at night they hid in caves, marshes or the forest. In

L‘Arbre des Batailles,

Honoré Bonet writes how the soldiers take ‘excessive payments and ransoms ... especially from the poor labourers who cultivate lands and vineyards‘, how ‘my heart is full of grief to see and hear of the great martyrdom that they inflict without pity or mercy on the poor labourers’. Even their own

seigneurs

persecuted them, seizing their crops and animals to pay ransoms and to make up for the decline in revenues caused by the Black Death. Finally the wretched toilers of the Beauvaisis took up knives and clubs and turned upon the lords who had failed to protect them. Dreadful stories circulated—of a lady who was raped by a dozen men and then forced to eat her roasted husband’s flesh before being tortured to ‘an evil death’ with all her children. Soon there were thousands of

jacques

north of the Seine, plundering and burning castles and manor houses. Etienne Marcel hoped to employ them as an auxiliary army and sent troops to their aid, politically a disastrous move. The shrewder King of Navarre gathered troops and then massacred the ill-armed mob near Meaux, thereby winning boundless popularity with the French nobility.

The Dauphin had fled from Paris in March. But the bourgeois were turning against Etienne Marcel, who at the end of July was cut down with an axe by one of his own supporters. The Dauphin returned, riding in amid the cheers of the fickle Parisians. Nevertheless Navarre was still at large, and defeated a royal army at Mauconseil the following month.

The Palace of the Savoy. ‘Henry. Duke of Lancaster, repaired or rather new built it, with the charges of fifty-two thousand marks [roughly £34,000] which money he had gathered together at the town of Bergerac.’ (Stowe)

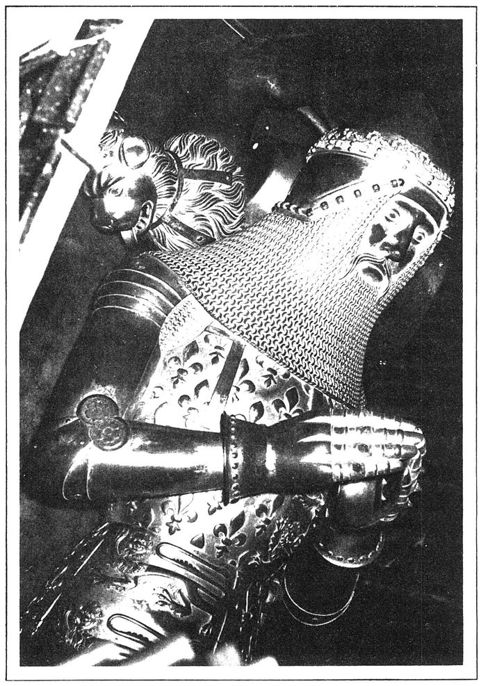

Edward, Prince of Wales—the Black Prince (1330—1376)

‘In war, was never lion rag’d more fierce,

In peace was never gentle lamb more mild,

Than was that young and princely gentleman.’

Meanwhile French envoys had been negotiating with the English to obtain the release of King John. In January 1358, by the first Treaty of London, the Dauphin agreed to surrender the sovereignty of Guyenne, together with the Limousin, Poitou, the Saintonge, Ponthieu and other regions—also in full sovereignty—which comprised at least a third of the entire realm of France. In addition John’s ransom was set at four million gold crowns. Edward in return was to renounce his claims to the French throne. However, although these were Edward’s own proposals, he was so encouraged by the Dauphin’s difficulties that he decided he wanted more—Anjou, Maine and Normandy, the Pas-de-Calais, together with the overlordship of Brittany. But the Estates declared that this second Treaty of London was ‘neither bearable nor feasible’. In fact Edward had probably never expected that these new demands would be met, and had made them simply as an excuse for further military intervention.

The English King now prepared to take the field himself, for the final campaign. Understandably he had no difficulty in raising an army of 30,000 men, all avid for plunder and encouraged by the wonderful victory at Poitiers. Most of his nobles accompanied him, and four of his sons, all recruiting large companies under the indenture system. Famous commanders were flooded with applications : so great was the reputation of Sir John Chandos that his company was superior to that of some earls, although he was only a knight. The army included 6,000 men-at-arms and countless wagons carrying kitchens, tents, mills, forges and even collapsible leather boats. Unfortunately instead of invading in the spring, the King did not land at Calais until 28 October.

The object of this campaign was to mount a mighty

chevauchée

which would culminate in Edward’s coronation as King of France at Rheims—the traditional place of consecration. After being joined by some German mercenaries and by many

routiers

(including Robert Knollys), Edward marched out of Calais on All Saints Day 1359, proceeding by way of Artois, the Thiérache and Champagne to Rheims, burning and slaying in the now customary manner. But Rheims knew he was coming and the Archbishop-Duke brought in provisions for a long siege. The English arrived before its strong walls in December in dreadful weather, and had to camp in snow.

Among those who rode with Edward was Geoffrey Chaucer, probably as a man-at-arms. He had had the misfortune to be taken prisoner on a raid into Brittany and the King was kind enough to contribute £ 16 towards his ransom. Obviously the poet had a grim time. Later he wrote : ‘There is ful many a man that crieth “Werre ! Werre !” that wot ful litel what werre amounteth.’

In January 1360, after cruel suffering by men and horses, Edward despaired of taking Rheims. He set off for upper Burgundy where, after frightful devastation—at Tonnerre the English drank 3,000 butts of wine—the Duke was only too glad to buy him off for 200,000 gold

moutons (£33,000).

The King then struck at Paris, laying waste the Nivernais en route. He camped at Bourg-la-Reine but did not feel strong enough to assault the capital. A Carmelite friar, Jean de Venette, who was in Paris at the time, recorded how everyone fled from the suburbs to take refuge behind the city walls. ‘On Good Friday and Holy Saturday the English set fire to Montlhéry and to Longjumeau and to many other towns round about. The smoke and flames rising from the towns to the sky were visible at Paris from innumerable places.’

(Ironically an incident had just occurred on the other side of the Channel which shocked all England. On 15 March 1360 some French ships attacked Winchelsea and burnt the town. Although the raiders spent only a single night on English soil, it was the first time such a thing had happened for twenty years. The English people were so terrified by this one small experience of what they had been inflicting on the French for decades that panic swept the entire country.)

Edward hoped that the French would come out from Paris to attack him. He sent heralds with a challenge to the Dauphin, who wisely refused it. Sir Walter Manny rode up to the walls and threw a javelin; even this elegant provocation failed. So, after spending a fortnight in the region of Paris, the English moved into the plain of the Beauce to inflict further misery. Near Chartres they were struck by a freak hail storm which threw the whole army into confusion. They called the day ‘Black Monday’.

Shortly afterwards the Abbot of Cluny arrived with peace proposals. Lancaster pointed out that while the King had fought a wonderful war, and though his men were profiting from it, it was far too expensive for his resources and would probably continue for the rest of his life. He advised Edward to accept the proposals—‘for, my lord, we could lose more in one day than we have gained in twenty years’. The King agreed; it had been his longest campaign and, in terms of strategy, was a failure. The fact that the Dauphin had made peace with Navarre and was beginning to improve his position generally may also have had something to do with Edward’s decision.

On I May 1360 negotiations began at the little hamlet of Brétigny near Chartres and within a week the Black Prince and the Dauphin had reached an agreement. King John’s ransom was to be cut to three million gold crowns (£500,000), while the English would reduce their territorial demands to those of the first Treaty of London—Guyenne in full sovereignty, together with the Limousin, Poitou, the Angoumois, the Saintonge, Rouergue, Ponthieu and many other districts, all in full sovereignty. On 24 October the Treaty of Brétigny was ratified at Calais. It was agreed that Edward would renounce his claim to the French throne and John his sovereignty over the ceded areas only when the latter had been transferred to the English. In the event, Edward stopped calling himself King of France, but on both sides no one bothered about formal renunciation.

The Dauphin signed the treaty in good faith, for France was exhausted. It seems unlikely that he had any secret reservations (as used to be suggested by some historians) and the transfer of territory began in autumn 1361. By spring the following year all save a few areas were in English hands. Edward was sovereign ruler not only of an independent Guyenne but of Aquitaine, a huge state which comprised one-third of France. While it would be wrong to detect any spirit of modern nationalism, undoubtedly the inhabitants of some of the ceded territories were most reluctant to change sovereigns—perhaps partly because of the injuries inflicted on them by the English, partly for fear of losing rights and privileges. But only at La Rochelle was there noticeable resentment; one Rochellois said that his fellow citizens ‘would obey with their lips but not with their hearts’, and others declared they were ready to pay half their wealth in taxes annually rather than be ruled by England. However, there was no real opposition and no bloodshed. In the event little changed, most mayors being confirmed in office; a number of Englishmen were put into the more important seneschalcies and castellanies but the greater part of the administration was left to Frenchmen. The ruler of the new state was not the King of England but the Black Prince at Bordeaux, whom Edward made Duke of Aquitaine.

In October 1360, when 400,000 gold crowns had been paid, two-thirds of the first instalment of his ransom, Edward III allowed John II to go home, though he had to leave three of his sons as hostages. (The sum was raised partly by crippling consumer taxes, on salt, wine and all other forms of merchandise, and by selling the hand of John’s eleven-year-old daughter Isabel to the son of the ill-famed Duke of Milan, Gian Galeazzo Visconti—‘the King of France sold his own flesh and blood’.) Unfortunately one of John’s sons, the Duke of Anjou, broke parole to rejoin a beautiful young wife and refused to return. The chivalrous King John therefore went back to London in 1364, to meet with a princely reception. In fact it was so princely that it has been suggested that the parties and banquets were too much for him. John II died at his palace of the Savoy on 8 April 1364, aged only forty-four. After a magnificent requiem at St Paul’s his remains were returned to France for interment at Saint-Denis.

If Edward III had not won the crown of France, it must none the less have seemed to contemporaries that he had carried off a very great prize. Beyond question the Brétigny settlement was a remarkable achievement. And it was amazing that a poor little country like England, formerly considered to be of no account militarily, could bring so rich and powerful a neighbour to her knees.

For the French of course it was a disaster. Edward’s triumph meant more than just ‘the abasement of the French monarchy’ and some lost battles. Prior Jean de Venette tells us what it meant to him. ‘The loss by fire of the village where I was born, Venette near Compiègne, is to be lamented, together with that of many others near by.’ He tells how there was no one to prune the vines or stop them rotting, no one to sow or plough the fields, no sheep or cattle even for the wolves, and how the roads were deserted. ‘Houses and churches no longer presented a smiling appearance with newly thatched roofs but rather the lamentable spectacle of scattered smoking ruins amid nettles and thistles springing up on every side. The pleasant sound of bells was heard indeed, not as a summons to divine worship but as a warning of hostile intention, so that men might seek out hiding places while the enemy were still on the way. What more can I say?’