The Most Evil Secret Societies in History (35 page)

Read The Most Evil Secret Societies in History Online

Authors: Shelley Klein

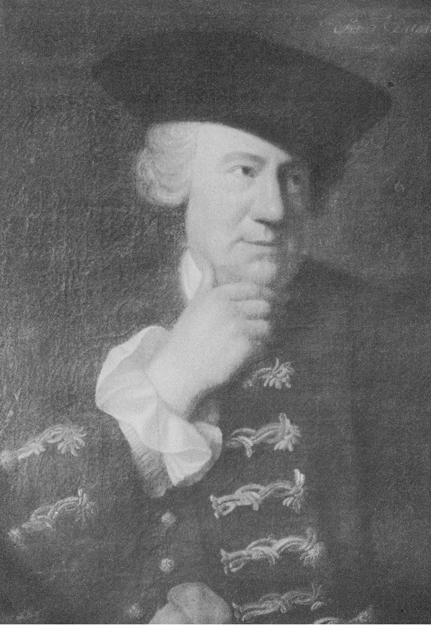

Sir Francis Dashwood's Hell Fire Club was also known as the Order of the Knights of St. Francis (or Knights of West Wycombe) and the Monks of Medmenham. The original twelve members took the names of the apostles with Sir Francis assuming the title of Jesus.

The sexual shenanigans enjoyed in the abbey, and the pomp and ceremony surrounding their rituals, encouraged membership of the club to blossom throughout the 1750s, to such an extent that Dashwood was eventually forced to split the members into two different categories. The first were known as the Superior Members and comprised of the twelve apostles plus Sir Francis. The second group were Inferior Members, of whom there may have been in the region of forty to fifty. When one of the Superior Members died, the remaining apostles would select a replacement from the Inferior group, among whom there was a great deal of competition to be granted the honor.

There was, of course, an initiation ceremony that everyone who wanted to join the Hell Fire Club, in any capacity, had to endure.

At midnight the candidate, clothed in a milk-white robe that flowed loosely around him, walked alone to the entrance of the chapel and knocked on the door. As it opened, he prostrated himself, then rose to walk slowly to the altar rails where he fell on his knees. The apostles sat in carved chairs along the wall, and Sir Francis, in his priestly robes, conducted the ceremony, attended by the poet Paul Whitehead, who kept records of the society's meetings, which he destroyed shortly before he died, years later, to try to keep secret the exact nature of the monks' rituals. (Whitehead's attempts at secrecy were only partially successful, for a good deal has been written by others about the Hell Fire Club ceremonies.) When the initiate sank to his knees before Sir Francis, the narcotic herbs burning in the braziers filled the chapel with fumes that dimmed the light of the candles. The candidate was called upon to abjure his faith and then to recite after Dashwood a perversion of the Apostles' Creed and the Articles of Faith. Next he was sprinkled with a mixture of salt and sulphur and baptized in a black font. He was then given some mystical name by which, in future, the brotherhood would always refer to him during meetings. After receiving the blood-red triangular Host, the candidate was finally admitted into full membership.

2

Unlike today, where there is rigorous scrutiny and general abhorrence of politicians who dabble in anything regarded as being even slightly outside what is considered ânormal behavior,' there were no such constraints in Sir Francis's time. Members of the twelve apostles were frequently drawn from the highest echelons of social and political life. Dashwood's second-in-command was none other than the Earl of Sandwich, who became First Lord of the Admiralty in 1748 and served in this capacity again in 1763 and 1771, in control of the Royal Navy and, therefore, one of the most powerful men of the period, despite being described as being all but incompetent.

Next in the Hell Fire Club's chain of command was the Earl of Bute. Like Sandwich, the Earl was a close friend of King George III, and in 1762 he became Prime Minister â the most powerful man in the country. Other members of the twelve apostles included the Archbishop of Canterbury's son, Thomas Potter, who was later made Vice-Treasurer for Ireland by Prime Minister William Pitt; the poet Charles Churchill who, although not well-known today, was regarded by contemporaries as one of England's greatest men of letters; the novelist Laurence Sterne; Lord Melcombe; and the politician George Selwyn. Joining this worthy crowd, William Hogarth frequently attended Hell Fire meetings to sketch the participants, sketches that would later appear in some of the artist's series of prints.

Given the high-society status of its membership, there is little doubt that the Hell Fire Club wielded huge influence in England's corridors of power. It can even be contended that Sir Francis Dashwood (who was appointed Chancellor of the Exchequer by King George III) and his fellows were effectively running the country. Yet there was one man who, although he dabbled with the Hell Fire Club, ultimately found its antics so distasteful that he almost destroyed the group.

Introduced to the club by Thomas Potter, John Wilkes was not an immediately likeable man, but Sir Francis Dashwood apparently felt fondly toward him and he was begrudgingly accepted into the fold.

The Hell Fire Club âmonks' traveled up the River Thames in gondolas for their ceremonies at Medmenham Abbey, arriving at night wearing white robes and carrying candles, looking for all the world like the ghosts of the Cistercian abbey's original twelfth-century inhabitants.

Born in 1727, Wilkes, a staunch Whig, was elected to Parliament as the Member for the Borough of Aylesbury, for which it is said he worked most diligently. His membership of the Hell Fire Club was not, however, quite so successful, for shortly after he gained entry he was expelled, following a prank he played on his fellow members. During one of their black masses, Wilkes, who had grown irritated by the anti-religious pretensions of the ceremonies, released a baboon dressed up as the Devil into the congregation. The result was pandemonium, with the Earl of Sandwich shouting aloud that the Devil was upon him, while other members collapsed in fright. Finally, the poor animal escaped through a window and order was restored, but not before the twelve apostles demanded of Sir Francis that Wilkes be excommunicated.

Wilkes felt little dismay or remorse at having been thrown out of the group; instead, he expressed his intense relief. He was glad to be shot of the Hell Fire Club and concentrated his energies on his blossoming political career, involving himself in one of the main debates of the time, about whether to give American Colonists representation in Parliament. As a Whig, Wilkes was all for it, but in this he was strongly opposed not only by the King, but also by âthe King's Friends' â a powerful group that included Bute, Sandwich, Dashwood

et al

. Whenever Wilkes attempted to make a speech in Parliament, the Hell Fire members combined to shout him down in rowdy exchanges.

In retaliation, Wilkes decided to use the pen rather than debate, employing the pages of a magazine that he had founded with Charles Churchill. The

North Briton

was a political pamphlet and, therefore, the best possible vehicle for the campaign Wilkes had in mind. Casting aside all caution, in the forty-fifth issue of the magazine he published a blistering attack on the government during which he included a choice piece of gossip (gleaned from his time with the Hell Fire Club) to the effect that Bute had had an affair with the King's mother. The result was extraordinary, for no sooner did Number 45 (as it soon became known) hit the streets than furious mobs began to hold demonstrations against both the government and the King. Neither Bute nor the King could move without being barracked, and the latter eventually invoked what was then known as a âgeneral warrant'. This allowed for the arrest of anyone thought to be associated with a criminal act, and the subject of the warrant was Wilkes.

The hapless Wilkes was duly arrested and incarcerated in the Tower of London. Yet far from calming the mood of the populace, by locking Wilkes up the King only provoked further rioting. Mobs ran amok, smashing windows and looting property until the King had to order Wilkes's release. Even then the mob wasn't satisfied and there remained a grave feeling of dissent among the general public. The King's Friends decided, therefore, to retaliate âin kind' by publishing a bawdy poem Wilkes had written during his time with the Hell Fire Club; a poem which, when released, was pretty much guaranteed to shock and appall the general public. Called

An Essay on Woman

, the piece was actually a parody of Alexander Pope's

An Essay on Man

beginning with the line, âAwake, my Sandwich' in imitation of Pope's âAwake, my St. John.' By this time the King's Friends among the Hell Fire Club had nothing to lose, for George III had become a laughing stock, Bute was discredited and Sandwich, whose reputation had never been good, was now universally loathed.

On November 15, 1763, the Earl of Sandwich stood up in Parliament and recited the entire poem to his fellow politicians. The result was astounding. There was much hilarity with, for instance, Lord Chesterfield standing to announce: âThank God, gentlemen, that we have a Wilkes to defend our liberties and a Sandwich to protect our morals,' after which there erupted a now very famous exchange between Sandwich and Wilkes, with the former shouting out, âSir, you will either die on the gallows or of the pox!' and the latter replying calmly, âThat, my Lord, depends on whether I embrace your principles or your mistress.'

After many heated exchanges, Parliament decided to delay any action against Wilkes (such as charging him on the grounds of indecency or blasphemy), but while the government hesitated, the King's Friends were not so tardy. They saw to it that the poem was distributed throughout London to a shocked public, whose support for Wilkes dramatically changed. Wilkes's friends, meanwhile, tried to help him by explaining that they still supported his policies, if not his private life. But Wilkes was in an incredibly difficult position for, unlike many of the Hell Fire Club members, he did not have a title or limitless funds at his disposal. Although he might have fought like with like and revealed more about the club's less salubrious practices, he could not afford a lengthy battle with the Hell Fire Club, especially since, having been branded a Satanist and a writer of obscene literature, his political career was in ruins. No one wanted to be seen consorting with such a man, certainly not members of his own party. Even Pitt, who had always been a staunch supporter of Wilkes, rose in Parliament and before everyone present stated that his fellow politician was âa blasphemer who did not deserve to be ranked among the human species.'

Even so, members of the Hell Fire Club, not satisfied that they had dragged Wilkes so low that his political career could never be revived, together hatched an even more wicked plan. They hired a lowly member of the House of Commons by the name of Samuel Martin to denounce Wilkes in front of everyone as a coward and a scoundrel. The insult called for nothing less than a duel. A time and place was arranged and on November 16, 1763, the pair faced each other with pistols. Although a first round of the duel was declared void, during the second Martin, who had put in a great deal of target practice prior to denouncing Wilkes in Parliament, wounded his opponent in the groin. The injury was not, however, fatal.

Having failed to have Wilkes killed, the Hell Fire Club now relied on the Commons to force a bill through Parliament declaring their former friend an outlaw for high treason against the King, as well as for producing indecent literature. In this, at least, they were successful and a warrant was put out for Wilkes's arrest, but he, wary of the Hell Fire Club's powers, had already fled to France.

Despite their success in the matter of John Wilkes, the repercussions of Number 45 meant that Bute's and Dashwood's political careers were effectively shattered, while Sandwich was forced to resign from the Admiralty (although he was later reinstated). The antics of the Hell Fire Club, on the other hand, continued unabated. Holding black masses, invoking the Devil to appear, enjoying orgies and drinking to excess, all carried on as normal. A few glitches were experienced along the way, such as the one caused by the publication of a novel entitled

Chrysal, or The Adventures of a Guinea

by Charles Johnson. The novel was a âconfidential,' with the golden guinea coin playing the main role, describing everything it saw on its strange journey through life from the time of its origin in a Peruvian gold mine. Part of its journey included a brief sojourn with a member of the Hell Fire Club where the guinea âwitnessed' a black mass and an orgy. Suddenly everyone wanted to visit Medmenham Abbey which, although not named in the book, was soon singled out as the most likely site. Crowds began to turn up to watch the âmonks' arriving by night, while others attempted to break into the gardens, sometimes even into the abbey itself. For a secret society this was a distinctly undesirable turn of events. Something had to be done and, as ever, Sir Francis Dashwood was just the man to do it.