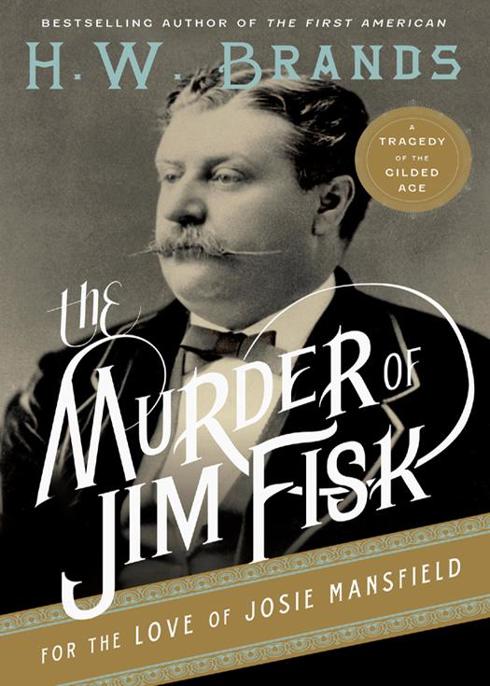

The Murder of Jim Fisk for the Love of Josie Mansfield

Read The Murder of Jim Fisk for the Love of Josie Mansfield Online

Authors: H. W. Brands

Tags: #History, #United States, #19th Century

H. W. BRANDS’S

AMERICAN PORTRAITS

The big stories of history unfold over decades and touch millions of lives; telling them can require books of several hundred pages. But history has other stories, smaller tales that center on individual men and women at particular moments that can peculiarly illuminate history’s grand sweep. These smaller stories are the subjects of American Portraits: tightly written, vividly rendered accounts of lost or forgotten lives and crucial historical moments.

H. W. BRANDS

The Murder of Jim Fisk

for the Love of Josie Mansfield

H. W. Brands is the Dickson Allen Anderson Centennial Professor of History at the University of Texas at Austin. He was a finalist for the Pulitzer Prize in biography for

The First American: The Life and Times of Benjamin Franklin

and for

Traitor to His Class: The Privileged Life and Radical Presidency of Franklin Delano Roosevelt

.

www.hwbrands.com

ALSO BY H. W. BRANDS

The Reckless Decade

T.R

.

The First American

The Age of Gold

Lone Star Nation

Andrew Jackson

Traitor to His Class

American Colossus

AN ANCHOR BOOKS ORIGINAL, JUNE 2011

Copyright © 2011 by H. W. Brands

All rights reserved. Published in the United States by

Anchor Books, a division of Random House, Inc., New York,

and in Canada by Random House of Canada Limited, Toronto.

Anchor Books and colophon are registered trademarks

of Random House, Inc.

Photo section credits: Picture History:

this page

; Library of Congress:

this page

,

this page

,

this page

,

this page

,

this page

; National Archives:

this page

; New York Public Library:

this page

,

this page

,

this page

.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Brands, H. W.

The murder of Jim Fisk for the love of Josie Mansfield : a tragedy

of the Gilded Age / H. W. Brands.

p. cm.—(American portraits)

eISBN: 978-0-307-74327-5

1. Fisk, James, 1835–1872—Assassination.

2. Fisk, James, 1835–1872—Relations with women.

3. Capitalists and financiers—United States—Biography.

4. Murder—New York (State)—New York—History—19th century.

5. Mansfield, Josie. 6. Showgirls—United States—Biography.

7. New York (N.Y.)—Biography. 8. New York (N.Y.)—Social life and

customs—19th century. I. Title.

CT275.F565B73 2011

974.7′103092—dc22

2010051174

Author photograph © Marsha Miller

Cover: Jim Fisk © Bettmann/Corbis: Josie Mansfield, photograph by William S. Warren © Picture History

Cover design by W. Staehle

v3.1

Contents

A gray blanket cloaks the trees of Montparnasse on a late

autumn morning. Smoke from the coal fires that heat the homes and shops along the narrow streets swirls upward to join the fog that congeals intermittently into drizzle. This part of Paris hides the signs of the Great Depression better than the blighted industrial districts, but the tattered storefronts, the shabby dress of men with nowhere to go, and the age of the few cars that ply the streets betray a community struggling to keep its soul together.

An old, oddly configured vehicle lumbers slowly along the cobbles. The dispirited pedestrians pay it no mind. Nor do they heed the two women and one man who walk behind it. The women appear to be locals; the shawls around their shoulders and the scarves on their heads could have been taken from the woman selling apples on one of the corners they pass or from the grandmother dividing a thin baguette among her four little ones. (Or could she be their mother? Hard times play evil tricks on youth and beauty.)

The man must be a foreigner. He dresses like an Englishman, one whom the Depression seems to have spared. His heavy wool coat and felt hat shield him from the damp; the coat’s collar and the hat’s brim hide his face from those around him. He might be an American; he walks more assertively than the average Englishman. He probably walked still more assertively when he was younger, although how many years have passed since that sprightly era is impossible to say.

The two women speak quietly to each other. Neither addresses the man, nor he them. The vehicle—whether it is a car or a truck is as much a puzzle as most else about this small procession—slows almost to a stop, then turns onto the leaf-strewn lane of the cemetery that these days forms a principal raison d’être of the neighborhood. It moves tentatively along the track, picking its way among the gravestones and mausoleums, beneath the connecting branches of trees left over from when the farm on this site began accepting plantings that didn’t sprout, not in this existence. The driver finally locates what he has been looking for, and he stops beside a fresh pile of dirt that is gradually turning dark as the drizzle soaks in. Two men shrouded in long coats suddenly but silently appear, as if from the earth itself. They stand at the rear of the vehicle as the driver lowers the gate. They grasp handles on the sides of the bare wooden box the vehicle contains, and with a nonchalance just shy of disrespect they hoist it out and set it on the ground between the pile of dirt and the hole from which the dirt has come.

They step aside, wordlessly letting the three mourners know that this is their last chance to commune with the deceased. One of the women produces, from a cloth bag, a small cluster of chrysanthemums and places it on the coffin. The man takes a rose from inside his coat and, with quiet tenderness, lays it beside the other flowers.

The three step back and gaze down at the wooden box. The drizzle turns to rain. The gravediggers slip short loops of rope inside the handles and lower the coffin into the grave. They pull up the ropes and begin shoveling the dirt back into its hole.

The hearse drives away, at a faster pace than before. The women walk off together. The man lingers. He looks at the grave, then at the city in the distance, then back at the grave. Finally he too departs.

Another day, another decade, another funeral. And

such

a

funeral. Lifelong New Yorkers cannot remember larger crowds, even to mark the Union victory in the Civil War. Many of those present today attended the victory celebration, but it is the nature of life in the great city, and the strength of the city’s appeal to outsiders, that a large part of the population has turned over in the seven years since the Confederate surrender at Appomattox. Today the newcomers crane to see what the fuss is about.

The funeral begins at the Grand Opera House on Twenty-third Street, where the body has lain for viewing. No one thinks the choice of venue odd—or at least none thinks it odder than that the Opera House is also home to one of America’s great railroads, the Erie, of which the deceased was a director and to which he, as owner of the Opera House, rented office space. The lavish interior of the house—the sweeping grand staircase, the twenty-foot mahogany doors embellished with the company initials “E. R.,” the bronze horses pawing the air furiously with their forehooves, the two-story mirror with the bust of Shakespeare on top, the sumptuous wall hangings, the carved and gilt columns, the cherubs disporting about the ceiling, the fountains spewing water into the air—has been rendered somewhat more somber for the sad occasion by the addition of black muslin tied up with black and white satin rosettes, to cover the cherubs and hide the gilt.

The visitors have been gathering since dawn; by eleven, when the doors open, they number ten thousand. They file slowly in, some entering by the door on the Twenty-third Street side, the others from Eighth Avenue. They approach the rosewood casket with its gold-plated handles. They see the deceased in his uniform as colonel of New York’s Ninth Regiment of militia. His cap and sword rest on his chest; his strawberry curls grace his forehead and temples. His face appears composed, albeit understandably pale; to some this seems strange, given the circumstances of the death. Flowers of various kinds—tuberoses, camellias, lilies—cover the lower portion of the body and surround the casket. Their scent fills the gallery. An honor guard of the Ninth Regiment stands at attention.

First to view the body are the other directors of the Erie Railroad and certain members of the New York bar and judiciary. When the general public is let in, several women professionally associated with the opera—of which the deceased was a prominent patron—burst into tears. His barber stops at the head of the casket and, with one hand, rearranges the curls while, with the other, he twists the tips of the dead man’s moustache.

As the last of the visitors depart, the funeral service commences. The chaplain of the regiment reads from the Episcopal prayer book. The wife, mother, and sister of the deceased, all veiled and dressed in black, sit quietly for the most part, only now and then airing a sigh or an audible sob. At the end of the reading, each of the women approaches the casket and kisses the dead man. The rank and file of the regiment march slowly past their fallen comrade and commander, paying silent tribute.

The casket is closed and covered with an American flag. The honor guard carries the casket to a waiting hearse. The regiment’s band, backed by musicians from one of New York’s German associations, tolls a dirge.

The funeral procession forms up. One hundred New York policemen take the lead, followed by the band, which has segued into “The Dead March in Saul.” A contingent of employees of the Erie Railroad come next, un-uniformed except for the black crape that adorns their arms. The full regiment, in parade dress, marches in triple file behind the Erie men. The hearse, pulled by four caparisoned black horses, rolls at a stately pace. A Negro groomsman guides the colonel’s favorite horse, a snorting black charger. The saddle is empty; reversed boots fill the stirrups. Officers of New York’s other regiments trail the stallion. Distinguished civilians, in handsome carriages, bring up the rear.

The procession moves slowly east on Twenty-third Street. Businesses have closed out of respect for the dead man’s passing; curtains and shades have been drawn on the private residences. Onlookers pack the sidewalks and spill into the streets. Others stand in the doorways and open windows of the buildings and on every balcony and stoop. Most are respectfully silent, but children shout and strangers who don’t know why the city has come to a midday halt insistently ask. More than a few of those familiar with the irreverence of the deceased talk and laugh in a different form of respect.

The procession turns north at Fifth Avenue. The regiment corners smartly, the others at their whim. Two blocks bring them to the New Haven depot, where a locomotive and train stand waiting. The pallbearers transfer the casket to a special car, draped in black, attached to the rear of the train. The family and close friends climb aboard the car to accompany their loved one to his final resting place in his native Vermont.

The locomotive puts on steam and slowly pulls the train out of the station. No one departs until the train has gone. “And thus passed from sight the mortal remains of one who might have been a vast power for good, had he made use of the glorious opportunities vouchsafed to him,” an eyewitness, more knowledgeable and literary than most, remarks. “Doubtless he had noble qualities, but they were hidden from the eyes of men, while his vices seemed to be on every man’s lips.”