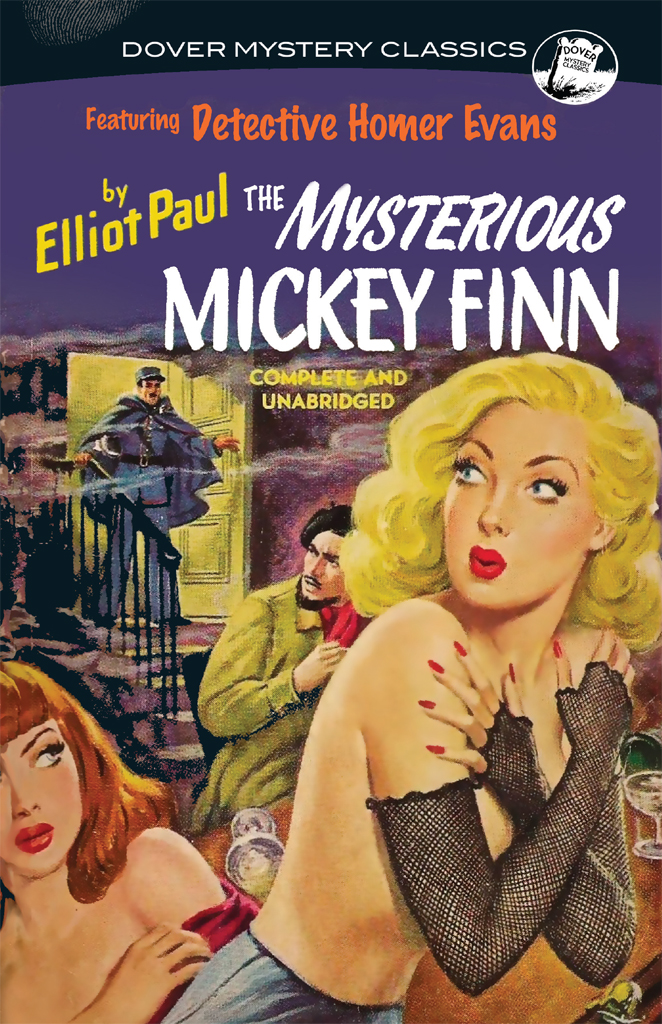

The Mysterious Mickey Finn

Read The Mysterious Mickey Finn Online

Authors: Elliot Paul

THE MYSTERIOUS MICKEY FINN

Elliot Paul

Dover Publications, Inc.

Mineola, New York

Bibliographical Note

Â

This Dover edition, first published in 1984 and reissued in 2014, is an unbridged republication of the work originally published by Modern Age Books, New York, 1939, under the title

The Mysterious Mickey Finn; or, Murder at the Café du Dome; an International Mystery.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Paul, Elliot, 1891â1958

Â

The Mysterious Mickey Finn

Â

Reprint. Originally published: New York: Modern Age Books, 1939.

Â

p.cm.

Â

eISBN-13: 978-0-486-80296-1

Â

I. Title

PS3531.A852M97 1984

813'.52

84-7996

Manufactured in the United States by Courier Corporation

24751102 2015

1

The Rosy-Whiskered Morn in Montparnasse

5

In Which Twin Cheques Are Signed

6

The Philanthropist Disappears

9

A Glimpse of a Candle-Light Greco

10

Murder at the Café du Dôme

13

In Which a Tender Heart is Revealed Beneath a Gruff Exterior

18

A Potato-Masher Proves to be a Boomerang

19

Strange Bedfellows as it Were

23

Two Hearts That Cease to Beat as One, or to Beat at All for That Matter

24

Foul Play in an Old Château

25

A Truck-load of Contact Mines

26

Of the Odour of Saints and Sinners

31

In Which Many Hearts Are Gladdened

32

The Boyish Silhouette Gives Way to the Curved Outline

DEAR READER

My purpose in writing this book is to entertain you. I do not think that purpose is served by starting with the murder of a character who must necessarily be a perfect stranger to you. Do not be afraid, as you read the first few pages, that no one is going to die. The casualties are going to be fairly heavy before we get through.

If, however, you do not like this departure from the mould into which such stories unhappily have fallen, I promise you that next time I will introduce a dead body into the preface, before the book is properly started at all.

THE AUTHOR

The characters in this book have had to be toned down somewhat for the family trade, but otherwise are pretty much as they were in the heyday of the American occupation of Montparnasse in the postwar years.

The Rosy-Whiskered Morn in Montparnasse

E

LEVEN A.M.

is a dull hour on the

terrasse

of the Café du Dôme. The early risers of Montparnasse have already had coffee and rolls, the larger group who are in Paris frankly for loafing and inviting their thirsts, stay in bed until afternoon. The French of the neighbourhood, small shop keepers, butcher boys, dairy girls, bill collectors, and the like, are scurrying to and fro with their minds on their retail business.

On the spring morning in question, Homer Evans, one of the few who were sitting in front of that famous

café,

was there because he had not yet been in bed. He was a tall, broad-shouldered, fair-haired young man who looked sturdy without being athletic, and responsive although indolent. He did not lounge awkwardly over table and chair like a character from Mark Twain, and decidedly he did not sit erect and perform moral gymnastics like an American business man. He looked as if he had lived easily and well, neither rich nor poor, but nobody in Montparnasse knew how he did it, where his funds came from or what his antecedents were. His friends, and he had scores of them, secretly wondered why a man of such brilliance and poise was content to let his talents lie fallow. For while there was considerable doubt as to the artistic merits and abilities of many of the residents of the quarter, Evans could write and paint with the best of them. His output, however, was small. He had written one short monograph entitled âDemocracies, Ancient and Modern' and had painted only one picture, a portrait of his friend and drinking companion, a Norwegian-American artist named Hjalmar Jansen. He had sat for Hjalmar, as he had sat for many other painters, and when the big Norwegian had got through, Evans had borrowed the paints, rags, and brushes and had turned out a work of art that caused other hard-working artists to wince with envy. One of them, plump Rosa Stier, had almost flown into a rage.

âYou've no right to do that, damn you, Homer,' she had said. And even Hjalmar Jansen had grunted uncomfortably. âWhen I think of the work I put in to train my hand and my eyes, when you consider these poor bastards all over the quarter who'd give their right eye to paint like that ...'

âI swear by all that's holy that I'll never do it again,' Evans said, and he kept his word.

Music, of all the arts, meant the most to Evans, so much that he seldom talked about it. Each year he would spend January and February in Spanish Morocco, usually at Melilla where he knew an Arab

café

in which the musicians played all night long, with their throbbing, insistent rhythm and unending simple melodies. Then he would return to Paris for the best part of the concert season.

He liked particularly to hear finger exercises played, over and over again. He loved to lie in bed and listen to those musical Arabesques repeat themselves and run idly through slight variations. For two years, until the previous December, he had hired a music student to play finger exercises on his grand piano each day between eleven and one, and when the pretty and earnest young girl from Montana had gone back home to teach he had been vaguely uneasy for weeks, although it occurred to him afterwards that he had never known her name.

On the Tuesday morning on which this story opens Evans had not been to bed, not because alcoholic excesses had driven him to carry on beyond the natural ending of a party. He had been showing his publisher and some visiting Americans the night life of the city. They had tasted the right food, and a staggering number of the right kind of drinks, had seen busy people at work in the most commendable of all labours, the continuance of the food supply. Just to remind his guests that beneath the frosting of society are strata with no margins for defending their humanity, he had taken them to the huge square in front of the city hospital, just after two o'clock, at the hour when all the tramps and derelicts are chased out of the squalid bars and from beneath the bridges. Standing in the shelter of the great cathedral, the Americans had watched the furtive army of the disinherited slink across the square on the way to the market where some of them might earn a few

sous

and the others scrape up discarded carrots and cabbage leaves from the slippery sidewalks. It was one of Evans' few acts of self-discipline, mingling now and then with that unholy and wretched crowd, and usually he performed it alone. But his publisher had wanted to see everything, so after a dinner at the Café de Paris, an hour at the Folies Bergère, a drink or two

chez

Weber, and the stimulating popular quarter around the place Clichy, instead of treating his guests to a session of living pictures in the notorious rue Blondel, Homer had confronted them unexpectedly with the lowest of the low, in one of their moments of greatest discomfort. It was his sense of the dramatic, perhaps, and more likely something more. At any rate, it had given his publisher such a shock that, later, he had viewed the miraculous pyramids of carrots and cauliflower, the entire place St Eustache covered with baskets of strawberries, the Bourse flanked with fifty thousand mushrooms, in a daze and had harangued Evans in every market

café

on the subject of his idleness, on the number of books he might have been turning out, on the injustice of burying his thirty talents, in contradiction with Biblical precedent and the practice of right-thinking people everywhere. After the dawn, involving green and gold behind the spires of Notre Dame, after the last bat had zigzagged between the buildings of the rue de la Huchette, Evans had retired to his own quarter, Montparnasse, again to think it over. He had thought it over and once more decided he was on the right track. No books, no paintings, no fame. If he wrote as he could write, no one would publish it, least of all the dapper young president of the Acorn Press, and if the stuff were published, no one would read it. And if someone read it, he would probably not understand it. And if he did by chance understand it, it would make him feel badly.

A negative resolve is not conducive to sleep, so Evans had sat calmly on the

terrasse

of the Select watching the blue deepen behind the Coupole. Then, at the appropriate hour, he had shifted over to the Dôme and had just about decided that after lunch he would take some rest when Hjalmar Jansen appeared.

No doubt âappeared' is too light a verb to use in connexion with the hulking Norwegian painter. He lumbered across the street, letting the traffic dodge him as best it could, and before he had approached nearer than fifty yards, Evans could see that his friend had something on his mind.

âWhat the hell?' Evans asked, startling the Norwegian into recognizing him. âOne would think, by the looks of your face, that the English girl had made you marry her.'

âWorse than that,' said Jansen, making the straw chair creak with his weight as he sat at Evans' table.

âThere's nothing worse than that,' Evans said. âHer feet. ...'

âThis is serious,' Jansen said. âHugo Weiss is in town.'

The End of a Fiscal Year

H

UGO

W

EISS

was known in every capital of the western world as a multi-millionaire, a philanthropist and a patron of the arts. His home was New York and his refuge, Paris. He financed two symphony orchestras, kept a number of lesser opera companies circulating in America, was the moving director of at least half a dozen important museums. The aura of dollar signs and astronomical figures, of glittering diamond horseshoes, âla' in altissimo and miles of narrow galleries filled with dim paintings evoked by the mention of Hugo Weiss was so different from that of the Café du Dôme on a spring morning that Homer Evans, did not at first receive the import of his friend's remark. It was as if Hjalmar had said, âThey are scrubbing off the dome of St Paul's this morning,' or âNow is the time for all good men to come to the aid of their party.' Then Homer suddenly remembered that it was because of one thousand dollars advanced by Hugo Weiss that Hjalmar Jansen had been able to stay in Paris and paint during the past year, the fiscal year, from Hjalmar's viewpoint, that was drawing to a dismal close.