The Mystery of Olga Chekhova (34 page)

Read The Mystery of Olga Chekhova Online

Authors: Antony Beevor

Tags: #History, #General, #World, #Europe, #Military, #World War II, #Modern, #20th Century

REFERENCES

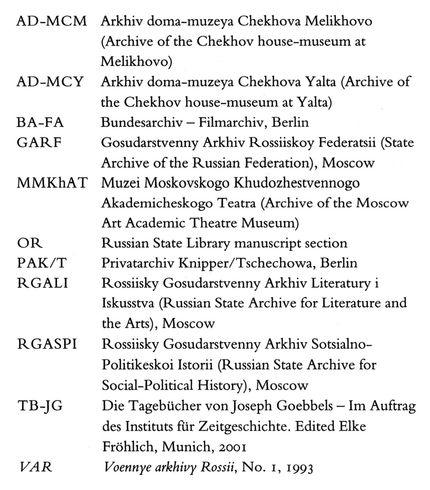

Abbreviations

Interviews

Lev Aleksandrovich Bezymenski (formerly Major GRU); Professor Tatyana Alekseevna Gaidamovich (widow of Lev Knipper); Vadim Glowna (Olga Chekhova’s grandson-in-law); Academician Andrei Lvovich Knipper (son of Lev Knipper); Aleksandr Aleksandrovich Melikov (Mariya Garikovna Melikova’s nephew); Eduard Prokofievich Sharapov (former Colonel KGB); Igor Aleksandrovich Shchors (former Colonel KGB); Mariya Vadimovna Shverubovich (granddaughter of Vasily Kachalov); Professor Anatoly Pavlovich Sudoplatov (son of General Pavel Sudoplatov); Albert Sumser (Olympic trainer and lover of Olga Chekhova in 1945); Vera Tschechowa (Olga Chekhova’s granddaughter); Zoya Vasileevna Zarubina (former Captain First Directorate NKVD, liaison officer for Lev Knipper and Mariya Garikovna).

SOURCE NOTES

1. The Cherry Orchard of Victory

p. 1

‘Attention, this is Moscow . . .’, quoted Porter and Jones, p.210.

p. 1

‘Gorky Street was thronged’, Ehrenburg, p. 187.

p. 2

‘kissed, hugged and generally feted’,

Manchester Guardian,

quoted Porter and Jones, p. 210.

p. 2

‘What immense joy ...’, ibid.

p. 2

Muscovites and clothes, Berezhkov, 1994, p. 322.

p. 4

The Cherry Orchard

special performance, AD-MCM, V. V. Knipper Fond.

p. 4

Maxim Gorky (1868—1936) was a pen name. His real name was Aleksei Maximovich Peshkov.

p. 4

‘deathly pale’, ‘smelled of a funeral’, Stanislavsky, 1924, p. 422.

p. 5 Stanislavsky’s real name was Konstantin Sergeievich Alekseiev, but to hide his youthful passion for acting from his father, Moscow’s most distinguished merchant, he adopted the stage name of Stanislavsky.

p.

5

‘a huge chapter’, Olga Leonardovna Knipper-Chekhova to Stanislavsky, Tiflis, 19 September 1920, Vilenkin (ed.), Vol. II, p.122.

p. 5

‘Just as he could wear . . .’, quoted Benedetti, 1988, p. 140.

p. 5

Stalin’s order for the execution of Meyerhold, Isaac Babel, Koltsov (the original of Karpov in Hemingway’s

For Whom the Bell Tolls)

and 343 others was signed on 16 January 1940. Meyerhold was shot on 2 February 1940, Shentalinsky, p. 70; Montefiore, p. 287.

p. 6

Beria’s former mistress, V. Matardze, and Meyerhold apartment, Parrish, p. 37.

p. 6

Tiflis is now Tbilisi.

p. 6

Moscow Art Theatre request in 1943 for honour for Olga Leonardovna Knipper-Chekhova refused, AD-MCM, V. V. Knipper Fond.

p. 7

Thousandth performance, letter to Olga Leonardovna Knipper-Chekhova, 12 November 1943, Vilenkin (ed.), Vol. II, p.206.

p. 7

Chekhov and Ranyevskaya. On 14 October 1903, he wrote to Olga Leonardovna Knipper-Chekhova that the part ‘will be played by you, there’s no one else’, Chekhov,

Pisma,

XI, pp. 273—4, quoted Benedetti, 1988, p. 128.

p. 8 ‘One

pair of hands is enough ...’, Vilenkin (ed.), Vol. I, p. 226, quoted Pitcher, p. 183.

p. 8

Stanislavsky’s sound effects. His admitted ‘enthusiasm for sounds on the stage’ during

The Cherry Orchard

provoked a sharp joke from Chekhov. ’“What fine quiet,” the chief person of my play will say,‘ he remarked to somebody nearby so that Stanislavsky could hear. ’“How wonderful! We hear no birds, no dogs, no cuckoos, no owls, no clocks, no sleigh bells, no crickets” ‘, quoted Stanislavsky, 1924, p. 420.

p. 8 Olga Leonardovna Knipper-Chekhova sights Olga Konstantinovna Chekhova, AD-MCM, V. V. Knipper Fond. The exact date of this special performance has been impossible to find in the files of the Moscow Art Theatre, which are clearly incomplete since there is no record of her appearing in any production of

The Cherry Orchard

between 1938 and 1948, though she completed her thousandth performance in 1943.

2. Knippers and Chekhovs

p. 9

August Knipper, the actress’s grandfather, however, was a metalworker. His son, Leonhardt Knipper, left Germany to seek his fortune as an engineer at the age of twenty-five. Leonard Knipper (he had soon dropped the Germanic spelling of his first name) moved to Glazov in the Urals to run a paper factory. His wife, Anna Salza, a talented pianist, came from Baltic German stock. She was ten years younger than him. Leonard and Anna spoke German at home and remained Lutherans, even though they took on Russian nationality. Konstantin, their eldest child, had been born before their move to Glazov, and Olga was born there, but in 1872 the family moved to Moscow, where a second son, Vladimir, or Volodya, was born later. They spent their winters there in a villa on the Novinsky bulvar. Knipper ancestry, V. V. Knipper, pp. 26-30; Helker and Lenssen, p. 22; and Andrei Lvovich Knipper, interview, 22September 2002. In her memoirs Olga Chekhova claims that the Knippers were of noble descent. This is not really true. The Knipper ancestor who had been the court architect of Wenceslas III, the Elector of Westphalia, had been ennobled, but the title was stripped from him later. Olga Chekhova’s father, Konstantin Leonardovich Knipper, was automatically ennobled according to Peter the Great’s ‘Table of Ranks’, purely because of his post as an official in the Ministry of Transport, but then so was Lenin’s father as an inspector of schools. Another branch of the Knipper family had gone to Russia in the eighteenth century. Karl Knipper, a ship-owner, had set up and sponsored a group of German actors in St Petersburg in 1787. V. V. Knipper, p. 22.

p. 10

‘my vaulting-horse’, quoted Rayfield, n. 37, p. 622.

p. 11

‘cows who fancy ...’, ‘Machiavellis in skirts’, quoted Rayfield, 1997, p. 183.

p. 11

‘Have you been carried away by his moire silk lapels?’, quoted ibid., p. 505.

p. 12

Just before Chekhov’s death in 1904, Gorky was so provoked by a jealous attack from Olga Leonardovna Knipper-Chekhova’s former lover Nemirovich-Danchenko that he severed his ties with the Moscow Art Theatre. For the row between Nemirovich-Danchenko and Gorky in April 1904, see Benedetti, 1988, pp.139-48.

p. 13

‘little skeleton’, OR 33⅙2/27, quoted Rayfield, 1997, p. 118.

p. 13

‘Natalya is living in my apartment...’, 24. October 1888, quoted ibid., p. 179. These two children, Nikolai (Kolya) and Anton, were the children of Aleksandr and his common-law wife, the divorcee Anna Ivanovna Khrushchiova-Sokolnikova.

p. 14

‘thunderous voice’, echov, 1992, p. 12.

p. 15

‘Am in the Crimea’, ibid., p. 20.

p.

15

‘Misha is an amazingly intelligent boy’, Sergei Mikhailovich Chekhov, MS, AD-MCM/Sakharova/File 81.

p. 16

Konstantin Knipper’s wife’s name in her passport had been Yelena Yulievna Ried, but within the family she was Luise or Lulu, and later, when a grandmother, Baba.

p. 16

Her school records give her date of birth as 13 April 1897, but that was according to the old Orthodox calendar, RGALI 677/ ¼087.

p. 16

Olga Konstantinovna Chekhova’s birthplace according to official documents, AD-MCM, V. V. Knipper Fond.

p. 17

‘a hunting lodge’, Tschechowa, 1952a, p. 53.

p.18

‘I hellishly wanted ...’, quoted Rayfield, 1997, p. 573.

p. 18 ‘which looked like a see-saw’, Andrei Lvovich Knipper, interview, 22 September 2002.

p. 18

‘first music shock’, L. K. Knipper, p. 11.

p. 20

‘unruly character’, ibid.

p. 20

Olga Chekhova’s school record, Stroganov Art School, personal file of Olga Konstantinovna Knipper, 1913, RGALI 677/ ¼087.

p. 20‘such a beauty . . .’, Tatyana Alekseevna Gaidamovich, interview, 4January 2003.

p. 20

‘You will definitely ...’, Tschechowa, 1973, p. 37. Needless to say, her conversation with Duse is different in the two versions of her memoirs. In the 1952 version Duse also gives her a tiny pair of silver ice-skates for a doll and says: ‘You are so beautiful that you should be kept away from the theatre!’, Tschechowa, 1952a, p. 69.

3. Mikhail Chekhov

p

.

21

Mikhail Chekhov at Maly Theatre School, Sergei Mikhailovich Chekhov, MS, AD-MCM/Sakharova/File 81.

p. 21

October 1911, echov, 1992, p. 44.

p. 21

‘He was short, thin and moved restlessly ...’, Sergei Mikhailovich Chekhov, MS, AD-MCM/Sakharova/File 81.

p. 22

‘as if I had to ...’, echov, 1992, p. 57.

p. 22

‘Thank you, Aunt Masha ...’, quoted Sergei Mikhailovich Chekhov, MS, AD-MCM/Sakharova/File 81.