Read The Myths and Legends of Ancient Greece and Rome Online

Authors: E. M. Berens

Tags: #Greece, #Rome, #god, #gods, #zeus, #Jupiter, #Aphrodite, #Poseidon, #Neptune, #Roman, #Greek, #Italian, #History, #Divinities, #Harpy, #Harpies, #Pegasus, #Pan, #Sacrifice, #Jason, #Argonauts, #Oedipus, #Troy

The Myths and Legends of Ancient Greece and Rome (16 page)

Â

Â

Â

Dionysus, also called Bacchus (fromÂ

bacca

, berry), was the god of wine, and the personification of the blessings of Nature in general.

Â

Â

The worship of this divinity, which is supposed to have been introduced into Greece from Asia (in all probability from India), first took root in Thrace, whence it gradually spread into other parts of Greece.

Dionysus was the son of Zeus and Semele, and was snatched by Zeus from the devouring flames in which his mother perished, when he appeared to her in all the splendour of his divine glory. The motherless child was intrusted to the charge of Hermes, who conveyed him to Semele's sister, Ino. But Hera, still implacable in her vengeance, visited Athamas, the husband of Ino, with madne

ss, and the child's life being no longer safe, he was transferred to the fostering care of the nymphs of Mount Nysa. An aged satyr named Silenus, the son of Pan, took upon himself the office of guardian and preceptor to the young god, who, in his turn, became much attached to his kind tutor; hence we see Silenus always figuring as one of the chief personages in the various expeditions of the wine-god.

Dionysus passed an innocent and uneventful childhood, roaming through the woods and forests, surrounded by nymphs, satyrs, and shepherds. During one of these rambles, he found a fruit growing wild, of a most refreshing and cooling nature. This was the vine, from which he subsequently learnt to extract a juice which formed a most exhilarating beverage. After his companions had partaken freely of it, they felt their whole being pervaded by an unwonted sense of pleasurable excitement, and gave full vent to their overflowing exuberance, by shouting, singing, and dancing. Their numbers were soon swe

lled by a crowd, eager to taste a beverage productive of such extraordinary results, and anxious to join in the worship of a divinity to whom they were indebted for this new enjoyment. Dionysus, on his part, seeing how agreeably his discovery had affected his immediate followers, resolved to extend the boon to mankind in general. He saw that wine, used in moderation, would enable man to enjoy a happier, and more sociable existence, and that, under its invigorating influence, the sorrowful might, for a while, forget their grief and the sick their pain. He accordingly gathered round him his zealous followers, and they set forth on their travels, planting the vine and teaching its cultivation wherever they went.

We now behold Dionysus at the head of a large army composed of men, women, fauns, and satyrs, all bearing in their hands the Thyrsus (a staff entwined with vine-branches surmounted by a fir-cone), and clashing together cymbals and other musical instruments. Seated in a chariot drawn by panthers, and accompanied by thousands of enthusiastic followers

, Dionysus made a triumphal progress through Syria, Egypt, Arabia, India, etc., conquering all before him, founding cities, and establishing on every side a more civilized and sociable mode of life among the inhabitants of the various countries through which he passed.

When Dionysus returned to Greece from his Eastern expedition, he encountered great opposition from Lycurgus, king of Thrace, and Pentheus, king of Thebes. The former, highly disapproving of the wild revels which attended the worship of the wine-god, drove away his attendants, the nymphs of Nysa, from that sacred mountain, and so effectually intimidated Dionysus, that he precipitated himself into the sea, where he was received into the arms of the ocean-nymph, Thetis. But the impious king bitterly expiated his sacrilegious conduct. He was punished with the loss of his reason, and, during one of his mad paroxysms, killed his own son Dryas, whom he mistook for a vine.

Pentheus, king of Thebes, seeing his subjects so completely infatuated by the riotous worship of this new divinity, and fearing the demoralizing effects of the unseemly nocturnal orgies held in honour of the wine-god, strictly prohibited his people from taking any part in the wild Bacchanalian revels. Anxious to save him from the consequences of his impiety, Dionysus appeared to him under the form of a youth in the king's train, and earnestly warned him to desist from his denunciations. But the well-meant admonition failed in its purpose, for Pentheus only became more incensed at this interference, and, commanding Dionysus to be cast into prison, caused the most cruel preparations to be made for his immediate execution. But the god soon freed himself from his ignoble confinement, for scarcely had his jailers departed, ere the prison-doors opened of themselves, and, bursting asunder his iron chains, he escaped to rejoin his devoted followers.

Meanwhile, the mother of the king and her sisters, inspired with Bacchanalian fury, had repaired to Mount Cithaeron, in order to join the worshippers of the wine-god in those dreadful orgies which were solemnized exclusively by women, and at which no man was allowed to be present. Enraged at finding his commands thus openly disregarded by the members of his own family, Pentheus resolved to witness for himself the excesses of which he had heard such terrible reports, and for this purpose, concealed himself behind a tree on Mount Cithaeron; but his hiding-place being discovered, he was dragged out by the half-maddened crew of Bacchantes and, horrible to relate, he was torn in pieces by his own mother Agave and her two sisters.

An incident which occurred to Dionysus on one of his travels has been a favourite subject with the classic poets. One day, as some Tyrrhenian pirates approached the shores of Greece, they beheld Dionysus, in the form of a beautiful youth, attired in radiant garments. Thinking to secure a rich prize, they seized him, bound him, and conveyed him on board their vessel, resolved to carry him with them to Asia and there sell him as a slave. But the fetters dropped from his limbs, and the pilot, who was the first to perceive the miracle, called upon his companions to restore the youth carefully to the spot whence they had taken him, assuring them that he was a god, and that adverse winds and storms would, in all probability, result from their impious conduct. But, refusing to part with their prisoner, they set sail for the open sea. Suddenly, to the alarm of all on board, the ship stood still, masts and sails were covered with clustering vines and wreaths of ivy-leaves, streams of fragrant wine inundated the vessel, and heavenly strains of music were heard around. The terrified crew, too late repentant, crowded round the pilot for protection, and entreated him to steer for the shore. But the hour of retribution had arrived. Dionysus assumed the form of a lion, whilst beside him appeared a bear, which, with a terrific roar, rushed upon the captain and tore him in pieces; the sailors, in an agony of terror, leaped overboard, and were changed into dolphins. The discreet and pious steersman was alone permitted to escape the fate of his companions, and to him Dionysus, who had resumed his true form, addressed words of kind and affectionate encouragement, and announced his name and dignity. They now set sail, and Dionysus desired the pilot to land him at the island of Naxos, where he found the lovely Ariadne, daughter of Minos, king of Crete. She had been abandoned by Theseus on this lonely spot, and, when Dionysus now beheld her, was lying fast asleep on a rock, worn out with sorrow and weeping. Wrapt in admiration, the god stood gazing at the beautiful vision before him, and when she at length unclosed her eyes, he revealed himself to her, and, in gentle tones, sought to banish her grief. Grateful for his kind sympathy, coming as it did at a moment when she had deemed herself forsaken and friendless, she gradually regained her former serenity, and, yielding to his entreaties, consented to become his wife.

Dionysus, having established his worship in various parts of the world, descended to the realm of shades in search of his ill-fated mother, whom he conducted to Olympus, where, under the name of Thyone, she was admitted into the assembly of the immortal gods.

Among the most noted worshippers of Dionysus was Midas, the wealthy king of Phrygia, the same who, as already related, gave judgment against Apollo. Upon one occasion Silenus, the preceptor and friend of Dionysus, being in an intoxicated condition, strayed into the rose-gardens of this monarch, where he was found by some of the king's attendants, who bound him with roses and conducted him to the presence of their royal master. Midas treated the aged satyr with the greatest consideration, and, after entertaining him hospitably for ten days, led him back to Dionysus, who was so grateful for the kind attention shown to his old friend, that he offered to grant Midas any favour he chose to demand; whereupon the avaricious monarch, not content with his boundless wealth, and still thirsting for more, desired that everything he touched might turn to gold. The request was complied with in so literal a sense, that the now wretched Midas bitterly repented his folly and cupidity, for, when the pangs of hunger assailed him, and he essayed to appease his cravings, the food became gold ere he could swallow it; as he raised the cup of wine to his parched lips, the sparkling draught was changed into the metal he had so coveted, and when at length, wearied and faint, he stretched his aching frame on his hitherto luxurious couch, this also was transformed into the substance which had now become the curse of his existence. The despairing king at last implored the god to take back the fatal gift, and Dionysus, pitying his unhappy plight, desired him to bathe in the river Pactolus, a small stream in Lydia, in order to lose the power which had become the bane of his life. Midas joyfully obeying the injunction, was at once freed from the consequences of his avaricious demand, and from this time forth the sands of the river Pactolus have ever contained grains of gold.

Representations of Dionysus are of two kinds. According to the earliest conceptions, he appears as a grave and dignified man in the prime of life; his countenance is earnest, thoughtful, and benevolent; he wears a full beard, and is draped from head to foot in the garb of an Eastern monarch. But the sculptors of a later period represent him as a youth of singular beauty, though of somewhat effeminate appearance; the expression of the countenance is gentle and winning; the limbs are supple and gracefully moulded; and the hair, which is adorned by a wreath of vine or ivy leaves, falls over the shoulders in long curls. In one hand he bears the Thyrsus, and in the other a drinking-cup with two handles, these being his distinguishing attributes. He is often represented riding on a panther, or seated in a chariot drawn by lions, tigers, panthers, or lynxes.

Being the god of wine, which is calculated to promote sociability, he rarely appears alone, but is usually accompanied by Bacchantes, satyrs, and mountain-nymphs.

The finest modern representation of Ariadne is that by Danneker, at Frankfort-on-the-Maine. In this statue she appears riding on a panther; the beautiful upturned face inclines slightly over the left shoulder; the features are regular and finely cut, and a wreath of ivy-leaves encircles the well-shaped head. With her right hand she gracefully clasps the folds of drapery which fall away negligently from her rounded form, whilst the other rests lightly and caressingly on the head of the animal.

Dionysus was regarded as the patron of the drama, and at the state festival of the Dionysia, which was celebrated with great pomp in the city of Athens, dramatic entertainments took place in his honour, for which all the renowned Greek dramatists of antiquity composed their immortal tragedies and comedies.

He was also a prophetic divinity, and possessed oracles, the principal of which was that on Mount Rhodope in Thrace.

The tiger, lynx, panther, dolphin, serpent, and ass were sacred to this god. His favourite plants were the vine, ivy, laurel, and asphodel. His sacrifices consisted of goats, probably on account of their being destructive to vineyards.

Â

Bacchus Or Liber

Â

The Romans had a divinity called Liber who presided over vegetation, and was, on this account, identified with the Greek Dionysus, and worshipped under the name of Bacchus.

The festival of Liber, called the Liberalia, was celebrated on the 17th of March.

Â

Â

Â

Aïdes, Aïdoneus, or Hades, was the son of Cronus and Rhea, and the youngest brother of Zeus and Poseidon. He was the ruler of that subterranean region called Erebus, which was inhabited by the shades or spirits of the dead, and also by those dethroned and exiled deities who had been vanquished by Zeus and his allies. Aïdes, the grim and gloomy monarch of this lower world, was the suc

cessor of Erebus, that ancient primeval divinity after whom these realms were called.

The early Greeks regarded Aïdes in the light of their greatest foe, and Homer tells us that he was “of all the gods the most detested,” being in their eyes the grim robber who stole from them their nearest and dearest, and eventually deprived each of them of their share in terrestrial existence. His name was so feared that it was never mentioned by mortals, who, when they invoked him, struck the earth with their hands, and in sacrificing to him turned away their faces.

The belief of the people with regard to a future state was, in the Homeric age, a sad and cheerless one. It was supposed that when a mortal ceased to exist, his spirit tenanted the shadowy outline of the human form it had quitted. These shadows, or shades as they were called, were dri

ven by Aïdes into his dominions, where they passed their time, some in brooding over the vicissitudes of fortune which they had experienced on earth, others in regretting the lost pleasures they had enjoyed in life, but all in a condition of semi-consciousness, from which the intellect could only be roused to full activity by drinking of the blood of the sacrifices offered to their shades by living friends, which, for a time, endowed them with their former mental vigour. The only beings supposed to enjoy any happiness in a future state were the heroes, whose acts of daring and deeds of prowess had, during their life, reflected honour on the land of their birth; and even these, according to Homer, pined after their career of earthly activity. He tells us that when Odysseus visited the lower world at the command of Circe, and held communion with the shades of the heroes of the Trojan war, Achilles assured him that he would rather be the poorest day-labourer on earth than reign supreme over the realm of shades.

The early Greek poets offer but

scanty allusions to Erebus. Homer appears purposely to envelop these realms in vagueness and mystery, in order, probably, to heighten the sensation of awe inseparably connected with the lower world. In the Odyssey he describes the entrance to Erebus as being beyond the furthermost edge of Oceanus, in the far west, where dwelt the Cimmerians, enveloped in eternal mists and darkness.

In later times, however, in consequence of extended intercourse with foreign nations, new ideas became gradually introduced, and we find Egyptian theories with regard to a future state taking root in Greece, which become eventually the religious belief of the whole nation. It is now that the poets and philosophers, and more especially the teachers of the Eleusinian Mysteries, begin to inculcate the doctrine of the future reward and punishment of good and bad deeds. Aïdes, who had hitherto been regarded as the dread enemy of mankind, who delights in his grim office, and

keeps the shades imprisoned in his dominions after withdrawing them from the joys of existence, now receives them with hospitality and friendship, and Hermes replaces him as conductor of shades to Hades. Under this new aspect Aïdes usurps the functions of a totally different divinity called Plutus (the god of riches), and is henceforth regarded as the giver of wealth to mankind, in the shape of those precious metals which lie concealed in the bowels of the earth.

The later poets mention various entrances to Erebus, which were for the most part caves and fissures. There was one in the mountain of Taenarum, another in Thesprotia, and a third, the most celebrated of all, in Italy, near the pestiferous Lake Avernus, over which it is said no bird could fly, so noxious were its exhalations.

In the dominions of Aïdes there were four great rivers, three of which had to be crossed by all the shades. These three were Acheron (sorrow), Cocytus (lamentation), and Styx (intense darkness), the sacred stream which flowed ni

ne times round these realms.

The shades were ferried over the Styx by the grim, unshaven old boatman Charon, who, however, only took those whose bodies had received funereal rites on earth, and who had brought with them his indispensable toll, which was a small coin or obolus, usually placed under the tongue of a dead person for this purpose. If these conditions had not been fulfilled, the unhappy shades were left behind to wander up and down the banks for a hundred years as restless spirits.

On the opposite bank of the Styx was the tribunal of Minos, the supreme judge, before whom all shades had to appear, and who, after hearing full confession of their actions whilst on earth, pronounced the sentence of happiness or misery to which their deeds had entitled them. This tribunal was guarded by the terrible triple-headed dog Cerberus, who, with his three necks bristling with snakes, lay at full length on the ground; - a formidable sentinel, who permitted all shades to enter, but none to return.

The happy spirits, destined to enjoy the del

ights of Elysium, passed out on the right, and proceeded to the golden palace where Aïdes and Persephone held their royal court, from whom they received a kindly greeting, ere they set out for the Elysian Fields which lay beyond. This blissful region was replete with all that could charm the senses or please the imagination; the air was balmy and fragrant, rippling brooks flowed peacefully through the smiling meadows, which glowed with the varied hues of a thousand flowers, whilst the groves resounded with the joyous songs of birds. The occupations and amusements of the happy shades were of the same nature as those which they had delighted in whilst on earth. Here the warrior found his horses, chariots, and arms, the musician h

is lyre, and the hunter his quiver and bow.

In a secluded vale of Elysium there flowed a gentle, silent stream, called Lethe (oblivion), whose waters had the effect of dispelling care, and producing utter forgetfulness of former events. According to the Pythagorean doctrine of the transmigration of souls, it was supposed that after the shades had inhabited Elysium for a thousand years they were destined to animate other bodies on earth, and before leaving Elysium they drank of the river Lethe, in order that they might enter upon their new career without any remembrance of the past.

The guilty souls, after leaving the presence of Minos, were conducted to the gr

eat judgment-hall of Hades, whose massive walls of solid adamant were surrounded by the river Phlegethon, the waves of which rolled flames of fire, and lit up, with their lurid glare, these awful realms. In the interior sat the dread judge Rhadamanthus, who declared to each comer the precise torments which awaited him in Tartarus. The wretched sinners were then seized by the Furies, who scourged them with their whips, and dragged them along to the great gate, which closed the opening to Tartarus, into whose awful depths they were hurled, to suffer endless torture.

Tartarus was a vast and gloomy expanse, as far below Hades as the earth is distant from the skies. There the Titans, fallen from their high estate, dragged out a dreary and monotonous existence; there also were Otus and Ephialtes, those giant sons of Poseidon, who, with impious hands, had attempted to scale Olympus and dethrone its mighty ruler. P

rincipal among the sufferers in this abode of gloom were Tityus, Tantalus, Sisyphus, Ixion, and the Danaïdes.

Â

Tityus

, one of the earth-born giants, had insulted Hera on her way to Peitho, for which offence Zeus flung him into Tartarus, where he suffered dreadful torture, inflicted by two vultures, which perpetually gnawed his liver.

Â

Tantalus

was a wise and wealthy king of Lydia, with whom the gods themselves condescended to associate; he was even permitted to sit at table with Zeus, who delighted in his conversation, and listened with interest to the wisdom of his observations. Tantalus, however, elated at these distinguished marks of divine favour, presumed upon his position, and used unbecoming language to Zeus himself; he also stole nectar and ambrosia from the table of the gods, with which he regaled his friends; but his greatest crime consisted in killing his own son, Pelops, and serving him up at one of the banquets to the gods,

in order to test their omniscience. For these heinous offences he was condemned by Zeus to eternal punishment in Tartarus, where, tortured with an ever-burning thirst, he was plunged up to the chin in water, which, as he stooped to drink, always receded from his parched lips. Tall trees, with spreading branches laden with delicious fruits, hung temptingly over his head; but no sooner did he raise himself to grasp them, than a wind arose, and carried them beyond his reach.

Â

Sisyphus

was a great tyrant who, according to some accounts, barbarously murdered all travellers who came into his dominions, by hurling upon them enormous pieces of rock. In punishment for his crimes he was condemned to roll incessantly a huge block of stone up a steep hill, which, as soon as it reached the summit, always rolled back again to the plain below.

Â

Ixion

was a king of Thessaly to whom Zeus accorded the privilege of joining the festive banquets of the gods; but, taking advantag

e of his exalted position, he presumed to aspire to the favour of Hera, which so greatly incensed Zeus, that he struck him with his thunderbolts, and commanded Hermes to throw him into Tartarus, and bind him to an ever-revolving wheel.

Â

TheÂ

Danaïdes

were the fifty daughters of Danaus, king of Argos, who had married their fifty cousins, the sons of AEgyptus. By the command of their father, who had been warned by an oracle that his son-in-law would cause his death, they all killed their husbands in one night, Hypermnestra alone excepted. Their punishment in the lower world was to fill with water a vessel full of holes, - a never-ending and useless task.

Â

Â

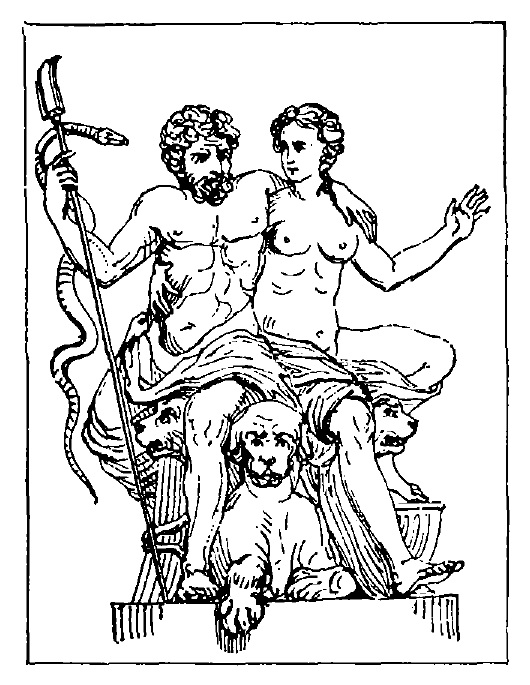

Aïdes is usually represented as a man of mature years and stern majestic mien, bearing a striking resemblance to his brother Zeus; but the gloomy and inexorable expression of the face contrasts forcibly with that peculiar benignity which so characterizes the countenance of the mighty ruler of heaven. He is seated on a throne of ebony, with his queen, the grave and sad Persephone, beside him, and wears a full beard, and long flowing black hair, which hangs straight down over his forehead; in his hand he either bears a two-pronged fork or the keys of the lower world, and at his feet sits Cerberus. He is sometimes seen in a chariot of gold, drawn by four black horses, and wearing on his head a helmet made for him by the Cyclops, which rendered the wearer invisible. This helmet he frequently lent to mortals and immortals.

Aïdes, who was universally worshipped throughout Greece, had temples erected to his honour in Elis, Olympia, and also at Athens.

His sacrifices, which took place at night, consisted of black sheep, and the blood, instead of being sprinkled on the altars or received in vessels, as at other sacrifices, was permitted to run down into a trench, dug for this purpose. The officiating priests wore black robes, and were crowned with cypress.

The narcissus, maiden-hair, and cypress were sacred to this divinity.

Â

Â

Pluto

Â

Before the introduction into Rome of the religion and literature of Greece, the Romans had no belief in a realm of future happiness or misery, corresponding to the Greek Hades; hence they had no god of the lower world identical with Aïdes. They supposed that there was, in the centre of the earth, a vast, gloomy, and impenetrably dark cavity called Orcus, which formed a place of eternal rest for the dead. But with the introduction of Greek mythology, the Roman Orcus became the Greek Hades, and all the Greek notions with regard to a future state now obtained with the Romans, who worshipped Aïdes under the name of Pluto, his other appellations being Dis (fromÂ

dives

, rich) and Orcus from the dominions over which he ruled. In Rome there were no temples erected to this divinity.

Â

Â

Â

Plutus, the son of Demeter and a mortal called Iasion, was the god of wealth, and is represented as being lame when he makes his appearance, and winged when he takes his departure. He was supposed to be both blind and foolish, because he bestows his gifts without discrimination, and frequently upon the most unworthy objects.

Plutus was believed to have his abode in the bowels of the earth, which was probably the reason why, in later times, Aïdes became confounded with this divinity.