The Nature of Ice (31 page)

THE WORK PARTYâTWO QUAD bikes in the lead, the blue Hägglund bringing up the rearâfollows the cane line back towards the station at what must feel to Vaughan, who's been shanghaied into joining Barney in the Hagg, a glacial pace. Chad can see Vaughan slumped in the passenger seat, headphones on to drown out the engine noise. Barney, on the other hand, with his huge knuckles raised like a ridge line over the steering wheel, could not be more content cruising along in a heated over-snow vehicle at fifteen kilometres an hour. Leaving them behind, Chad and Robbie sprint ahead on the bikes. Each time Robbie gets the nod from Chad he veers off the marked route to wind donuts across some irresistible slick of blue ice while they wait for the Hagg to catch up.

More speed

than sense

, Barney will be muttering in the Hagg. Robbie's alright, he's a good guy; his first season down here, been cooped up at the station too long.

Chad sees it first, a kilometre away down the hill: the bronzen sheen of the Russian aircraft wreck glinting in the sun. In the late sixties the DC 3 landed on the plateau to refuel. The old colour photos in the yearbook show it readying for takeoff on its way back to the Russian station. One second the plane was taxiing down the skiway, the next a katabatic gust shunted it off course, its starboard ski smashing through the lid of a crevasse and damaging a wing and a propeller. A forlorn crew of Russians escaped unscathed but their plane lay in the ice for the remainder of summer. Finally, the katabatic took charge of the plane one last time and flipped it belly up.

Yet in a slow, quiet way the plane's journey continues. The great dome of ice, two and a half thousand kilometres from pole to coast, three thousand metres thick at its deepest, gradually ferries the wreckage seaward as it inches downhill.

Even with the snow blown away, it's a fluke Chad even spotted the wreckageâapart from a wing, a ski and half an engineâthe wreck is buried in ice. He pips his horn to catch Robbie's attention and points out the plane. He doesn't for a moment expect Robbie to interpret his gesture as a signal to bolt down towards the wreckage, which he does at breakneck speed. Chad shouts after him, then blasts his horn. He can see the Hagg approaching, Barney through the windscreen shouting and throwing up his hands.

Chad signals that he'll bring him back.

As he follows warily over the same bumps and ridges that Robbie bounded across, he wants to wring the young guy's neck. Robbie finally slows, sensing something ahead. He brings the bike to a halt and stands tall on the foot braces. Chad swings his bike and brakes to avoid a ridge of névé obscured momentarily by the glare. His quad slides onto a patch of blue ice and he feels the front wheels spin. A sound like shattering glass cuts the air. Robbie turns to look back. But Chad already knows what it means. Too late he knows.

As the snow bridge gives way Chad loses his grip on the handlebars, slides backwards, his limbs flailing as if he were backstroking through sheets of tinted glass. He has time only to register the glow of ice, the surreal hue of the crevasse, before the wind is punched from his lungs by the bulk of a two-hundred-and-fifty-kilogram bike rammed up against him. Time ceases to be linear but curls around itself as the shine of red metal dims.

So this is the end

, Ma says matter of factlyâhers is the voice that winds through his head.

He feels the bike's petrol cap grinding into his belly like a biscuit cutter, pictures its scalloped edge imprinting his gut. He shifts his eyes to the left and then to the right; he can't turn his head, the adze of his ice axe digging into his throat. He thinks, though he has no way to be sure, he is wedged vertically, entombed upright (an odd predicament) between the bike and the wall of the crevasse. The seat crushes his chest, the petrol tank presses on his abdomen. He wets himself, hot against his groin; he cannot tell if his legs remain attached. He hears himself pant, thin and shallow like a tired dog. He ought to panic with the effort it takes to move air through his lungs yet he feels little concern. He begins to feel dreamy, neither afraid nor alone.

He remembers Ma trouncing him at Monopoly, and he, retaliating, launching himself across her as she counted out her properties, tickling her relentlessly until she collapsed into her belly laugh. She wasn't fast enough to escape, so she resorted to lying upon himâplastic hotels, paper money, dice and Chance cards falling aboutâher arms pinning his on either side. He remembers wanting to laugh and not being able toâhe could barely breathe beneath her weight. He remembers the smell of lotion on her skin, the trace of coffee on her breath, her hazel eyes so close to his he couldn't focus on them properly. She is here with him now, in the crevasse, trying to pin him down againâhim, a grown man. And though her face is as close as it could be, he has no trouble seeing. He can make out the laughter lines radiating from the corners of her eyes, webs of mulberry veins crowning her shiny cheeks. He has not before realised how young Ma is, or how her skin glows. But he wants her to stop, needs her to get up off him and call a truce so he can tell her something he didn't get the chance to say before. He wants her to know how sorry he is that she is gone, that for the longest time he thought the weight of it would crush him. He wants to hold her, cradle her. If he could change things, he tells her, if he could return to Go and collect two hundred, he would take more care pulling the net, would avoid the whip of a stingray's tail as easily as that; she'd have no need to drive to Hobart for a prescriptionâhis legs don't hurt at all.

Ma smiles as he speaks, her gaze full of grace.

Love, it's no

one's fault

, is all she says. He can tell, just by her eyes, how much she loves him. She holds out her hand and strokes his hair, over and over until he feels light enough to float away.

Something is winding itself around his neck and he feels Ma must be there, within his reach. It surprises him that she is so much stronger than he, her hands enormous on his back. She pulls him upward, as if he were a child, lifting him in jerks, saying,

I've got you, lad. I have you

, over and over. Ma's voice sounds gruff but not unkind. The layers of tinted glass begin to peel away until all that surrounds him is the palest veil of baby blue. Ma whispers she will have to leave him when they reach the light.

I know

, he says, though it hurts to speak and he wishes she could stay.

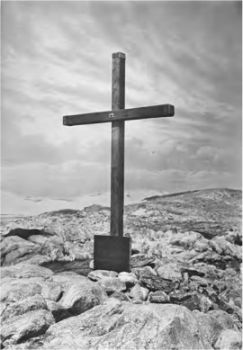

ERECTED

TO COMMEMORATE

THE SUPREME SACRIFICE

MADE BY

LIEUT. B.E.S. NINNIS, R.F.

AND

DR. X. MERTZ

IN THE

CAUSE OF SCIENCE

A.A.E. 1913

Melbourne

Sunday, 9 November 1913

Dearest Dougelly,

The Aurora leaves on Tuesday & I must add a last letter to

my little pile. And I do hope it will be the last letter I'll need to

write you for a very long while. This separation has been quite

long enough. We shall feel almost estranged . . .

We sent you a joint wirelessâperhaps you didn't get it? I

met Eitel, Hurley and Hunter. I like Hurley. They were very

good & I had a private view of the film the Aurora brought

back in 1912 when we were away . . .

Dearie I hope you & I are going to be happy. There is so

much to discuss before we are married that I can't write in a

letter. You understand, don't you, quite, when I repeat that it

isn't Paquita of 1911 you're coming back to? I may have

changed in ways you won't like but on the whole I don't think

so. We are very different in some waysâbut that shouldn't

prevent our happiness. Its to be âgive and take' on both sides.

I'm longing for your return to put me at rest. It is very

difficult not to think of the future. 21/2 years is a very long time

out of our lives. Oh well 3 months only now. Heaven give that

we aren't disappointed in each other. Our wants are different

now we are both older. Oh my dear man, come back and

reassure me that all will go well with us. I have lost confidence,

not in you, but in the future. I want your love again. It has

been hard to do without it so long.

I wonder will you return to Hobart or Adelaide. In

February the former would be the pleasantest but Adelaide

seems the likeliest. Capt. Davis has promised to let me know. It

is no good depending on you to. If you had wanted to wire you

could have. To answer mine & your brothers wire would not

have upset the men down there. However everyone has their

own way of thinking.

Mother & I will be waiting for you wherever you return. If

we know in time, of course . . .

My dear, dear man. Until FebruaryâI love you & the

next time I say that it will be in your arms. And will be

responded to, I hope. One sided correspondence is the limit.

Your own

Paquita

THE VOYAGE SOUTH HAD OPENED her eyes to the ice. Now, the passage homeâthe last of the bergs wound in fog, stretches of pack ice giving way to achromatic seaâreduces Freya's field of vision as if she were looking through a soft-focus lens. On the ship's helicopter deck, she stands with her eyes set astern, looking through a veil of mist, drawing images from her memory. With each increment of latitude they cross, her recollections of Antarctica feather at the edges. Even the sharpness of her final days at Davis Station has receded. It seems foolish, now, to have worked herself into a panic after her trip to Walkabout Rocks and woken Kittie in the middle of the night. As secretive as thieves they had removed from Freya's studio every DVD.and canister of film, locking irreplaceable images in Kittie's office for fear they might be tampered with. The echo of Adam Singer's threats still murmurs in her dreams.

Aurora Australis

crosses the Convergence, that innocuous blue line winding over the ship's chart to define the boundary of Antarctic waters. Only now does it undulate with meaning, for never has she felt so cast adrift. In the space of a day crisp air dissipates, the atmosphere warms, air turns sultry on her skin. She folds polar layers away, and though it's only nine or ten degrees Celsius outdoors, the dress code around the ship turns summery.

A wandering albatross appears to track their route, weaving over the wake, swooping to pluck some glinting morsel churned to the surface, rising briefly to wheel around the ship. With each monotonous hour of ocean, Freya's thoughts are tugged at and pulled askew. Most of those aboard turn their gaze northward, their anticipation of home palpable, but her eyes stay fixed on the bird. She contemplates the number of days and degrees it will take before the albatross peels away, a sign that the ocean is running out. Other than to breed the wanderer has no cause to turn to land; this body of steely water is its domain.

Freya sleeps during the day and walks the decks at night. So quickly now, evening light fades. As she climbs the outside steps of the ship she sees a faint smattering of stars across the southern sky. Only when she reaches the ship's bridge does she set her sights forward, gaining some comfort from the substantial span of ocean that still buffers her from the prospect of home, from a decision too life-changing to begin explaining to her husband in an email.

Some of the ship's crew are new this voyage but the captain, with the same boyish sweep of hair, remembers her from the trip down and nods as if they've been sailing this ocean together half their lives.

âDown next season?'

âA one-off,' she says, failing to sound bright.

âThat's what they all say. Eh, Parksie?' The sailor at the wheel, his face ruddy with acne, blushes in reply.

The captain flicks fair hair from his eyes. âI signed on for one summer. Same as Parksie. That was eighteen years ago.' He nods at the ocean. âOnce a place gets into you . . .'

AURORA AUSTRALIS

DOWNLOADS EMAILS TWICE each day. The communications room swarms with bodies; screens flicker, computers hum, keys click-clack. Three messages wait in her inbox, not one of them, Freya registers, from Marcus.

Dr Ev writes from Davis Station:

>> Now that things have quietened down around here, I've finally found some time to clear the backlog. A while ago you asked about the effects of starvation, why Douglas Mawson survived while Xavier Mertz did not. I can't offer anything conclusive but here are some thoughts to consider. The photos in various publications show Mawson as a tall, wiry fellow. Alongside him, Mertz looks considerably shorter with a stocky build. All things being equal, Mertz should have fared better on starvation rations than Mawson, given their different body types. Mertz, though, found eating the dogsâwho he had come to love as petsâ repulsive, the meat indigestible. It would have been as tough as old boots given the emaciated state the poor creatures were in. Perhaps when they divvied up the food Mertz ate a larger portion of softer, more âpalatable' pieces, i.e. the liver. Neither men had any way of knowing then that Greenland dog liver contains toxic quantities of vitamin A. Mawson had a harrowing trek home, hair falling out in clumps, festering boils, skin peeling away. Although he was savvy about nutrition in terms of calories and sledging rations, the effects of vitamins were not understood for another fifty years. He died in 1958 so would never have heard of the debilitating effects of hypervitaminosis A.