The Nazis Next Door (23 page)

Read The Nazis Next Door Online

Authors: Eric Lichtblau

This wasn’t supposed to happen, not anymore. When the Nazi office was created, the Justice Department declared that “every lead and every case will be vigorously pursued.”

The road to investigating the Nazis wasn’t supposed to stop at the door of the FBI, with its own informants protected from scrutiny. But when it came down to a choice between investigating suspected Nazis or protecting the FBI’s anti-Soviet informants, the fight against Communism still won out.

Rockler summed up the FBI’s dismissive attitude toward his new Nazi office with four words: “To hell with you.”

Months later, a Nazi office lawyer stumbled onto documents suggesting that the FBI had known about Nazi collaborators coming into America as far back as 1951, during the Hoover era. But when the lawyer asked the FBI to produce records on the issue, he got nowhere. “There may be reason

to suspect the FBI of willful concealment of embarrassing material,” the Justice Department lawyer wrote to his supervisor. “If the FBI is unwilling or unable to locate their own files when furnished with this much identifying information, then they damn well should let our OSI investigators go into the file room and do the job themselves.” That never happened, of course.

In one of the Justice Department’s highest-profile investigations, the deportation of the notorious Bishop Trifa in Michigan, the FBI destroyed

perhaps the single most critical piece of evidence in the entire case: a copy of the “Trifa Manifesto,” a virulent, Jew-hating screed that Trifa had put out in Romania in 1941 as the leader of a Nazi-supporting student group. Upset, the judge in the Trifa case ordered an investigation to determine what had happened. The FBI blamed a clerical error for the destruction.

Then there was the remarkable case of Ferenc Koreh, a former Nazi propagandist in New Jersey who had a whole band of FBI agents trying to protect him from deportation.

During the war, as an official at the Hungarian Ministry of Propaganda and as a newspaper editor, Koreh put out dozens of articles

and official, anti-Semitic propaganda attacking the Jews as “traitorous, unscrupulous, cheating people” and calling for a “de-Jewification of Hungarian life” and “final solution” to the country’s Jewish problem. (Some 440,000 Hungarian Jews were ultimately deported to Auschwitz and other Nazi camps.)

After coming to America in 1950, Koreh went on to become a vocal anti-Communist in New Jersey and an on-air broadcaster for the taxpayer-funded Radio Free Europe. When the Justice Department learned of Koreh’s canon of wartime hatred thirty-five years later, prosecutors tried to denaturalize him. He fought the charges—and he had help within the FBI. His daughter was an FBI agent, as was her live-in boyfriend. The pair, along with other supportive agents in the FBI’s New York field office, launched what amounted to a rogue investigation

of their own into Koreh’s case. They charged that the case against him was based on “forged” Communist documents. The daughter’s boyfriend, meanwhile, wrote a forty-six-page single-spaced internal report on FBI letterhead attacking the case not only against Koreh but also against Bishop Trifa. The FBI agent insisted that the two men were not Nazi supporters, but victims of a pro-Communist disinformation campaign. His colleagues at the Justice Department, the agent charged, had been duped.

The FBI, in a quasi-official report from its own agents, was now on record defending two high-level Nazi propagandists. Furious, a Justice Department official called the bureau’s conflict of interest “scandalous” and “so outrageous”

that it threatened to compromise the integrity of the FBI as a whole. The Justice Department was trying to deport Koreh, while agents at its premier investigative arm—the FBI—were defending him.

The headwinds from the FBI muddied up the prosecution and delayed the deportation case against Koreh for years, while he stayed in the country. In the end, however, Koreh grudgingly acknowledged

in court what prosecutors had charged all along: that he had published a slew of hateful, pro-Nazi propaganda that fueled the persecution of Hungary’s Jews. He was denied his government pension and stripped of his citizenship. He died in New Jersey under the toxic label of Nazi propagandist. Even his powerful friends and family members at the FBI, as hard as they tried, could not save Koreh from his wartime past.

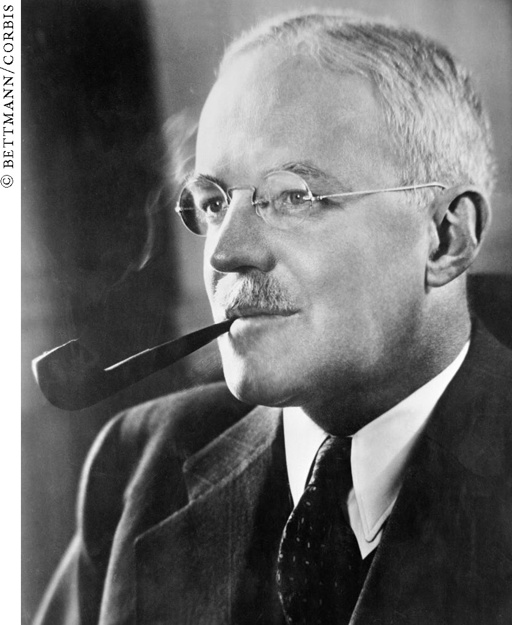

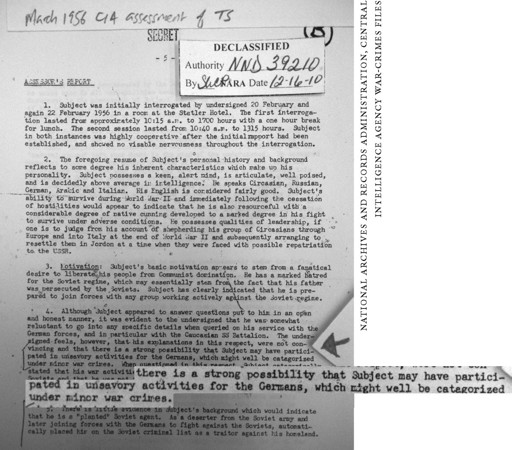

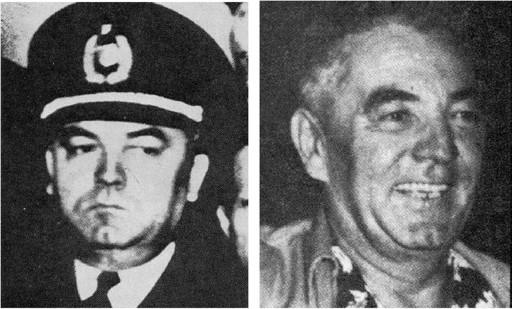

Nazi general Karl Wolff (left) with his boss, SS chief Heinrich Himmler, outside a Nazi train in 1942. Prosecutors at Nuremberg regarded General Wolff as Himmler’s “bureaucrat of death,” but “Wolffie,” a close friend of Hitler’s, escaped punishment for war crimes with the help of Allen Dulles (below), the American spy chief in Switzerland during the war.

Dulles (left, with his trademark pipe) said American spies “should be free to talk to the Devil himself ” if it would help in the war and believed the United States benefited from working with more “moderate” Nazis like Wolff.

Photos are reproduced courtesy of the United States Department of Justice unless otherwise noted.

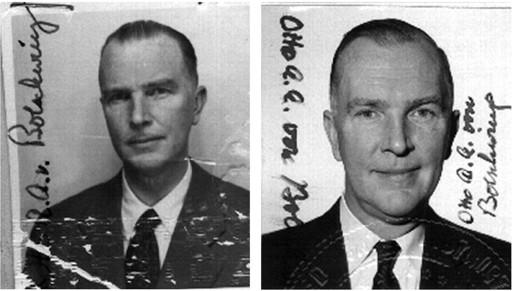

Otto von Bolschwing (shown here in immigration photos for his 1953 visa and 1959 naturalization) was a Prussian baron who served as a mentor and top advisor to Adolf Eichmann in the Nazi Security Service’s Jewish Affairs Office. The CIA used him as a spy in Europe after the war and brought him to America in the mid-1950s. A quarter century later, the Justice Department discovered him (shown here with his lawyer) living quietly at a nursing home near Sacramento.

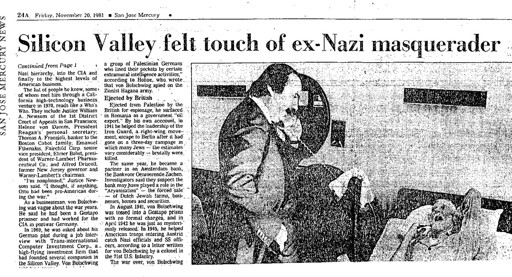

Used with permission of San Jose Mercury News Copyright © 2014. All rights reserved.

Tscherim “Tom” Soobzokov was considered an immigrant success story in his adopted hometown of Paterson, New Jersey. Secretly, he had been a Nazi Waffen SS officer in Europe before teaming up with the CIA and the FBI after the war. The Justice Department began investigating him in the 1970s, sparking protests in New Jersey.

The CIA, after interviewing Soobzokov extensively in 1956 for a job as a spy against the Soviets, concluded that he was probably involved in “minor war crimes” with the Nazis, but the agency hired him even so.

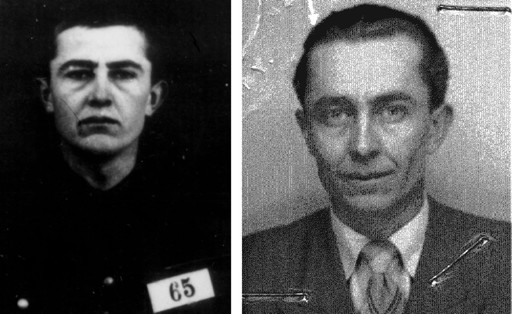

As a cabinet minister in the Nazi puppet state of Croatia (left), Andrija Artukovic was implicated in the murders of hundreds of thousands of Serbs, Jews, Roma, and other non-Aryans incarcerated in camps. He lived in Southern California (right) for nearly four decades before he was extradited to Yugoslavia in 1986 and convicted of war crimes.

Jakob Reimer was a Nazi officer (left) and trainer at the Trawniki concentration camp and took part in the brutal liquidation of the Warsaw ghetto. After coming to America (right), he ran a restaurant in New York for years and sold potato chips. He died in 2005 while prosecutors were still trying to deport him.