The New Empire of Debt: The Rise and Fall of an Epic Financial Bubble (21 page)

Read The New Empire of Debt: The Rise and Fall of an Epic Financial Bubble Online

Authors: Addison Wiggin,William Bonner,Agora

Tags: #Business & Money, #Economics, #Economic Conditions, #Finance, #Investing, #Professional & Technical, #Accounting & Finance

On the other hand, war also was a serious matter. And central banks were asked to help finance the war. This difficult position was made even worse in 1914 when the threat of war caused a drop in stock prices—wiping out much of the liquidity that might be sopped up for wartime finance. The European nations needed to borrow vast amounts to cover the war expenses. But each additional unit of currency further reduced the gold cover, or the ability of the borrowing nation to pay its debts with real money.

Readers will be quick to notice the parallels to the global financial system of 2005. The Europeans wanted to increase the consumption of war materiel. Now, Americans consume other things as if they were fighting for their lives. Cannons and bullets were not much different from big-screen TVs and automobiles; they were quickly used up with no economic progress to show for it. From 1914 to 1918, France and Britain needed U.S. financing to conduct war beyond their means. Now, America turns to its principal suppliers in Asia and asks for credit. Without it, the United States cannot continue consuming at its present rate. In 1914, the world’s most important supplier was the United States. France, Britain, and Russia (and to a much lesser extent, Germany, early in the war) had to turn to the United States for supplies. But since they consumed more than they earned, they put their gold reserves at risk. France dealt with this problem early on by simply going off the gold standard. Britain remained on the gold standard throughout the war, barely, but only by the grace of U.S. creditors.

Fortunately for Britain, the United States did not force the issue. (Fortunately for America 90 years later, its major creditors in Asia do not seem to want to force the issue either—at least, not yet. Even without a gold standard, China and Japan could wreak havoc with the dollar any time they chose. For the moment, like America in 1914 to 1916, they are happy to take the orders and increase market share, knowing that their major customer cannot really afford to pay for all that they send her.)

As the war grew more and more grim, not only was the honest money of the gold standard abandoned by most belligerents, the export of gold to settle accounts was expressly forbidden (under cover of fear that the gold would fall into enemy hands). Each nation began increasing its supply of money, issuing more paper currency, borrowing more and more money from foreign (mostly American) and domestic sources, and spending far beyond its means.

France was already heavily in debt when the war began, with a consolidated debt in July 1914 of 27,000 million francs, in arrears already by 967 million. Normally, the French assembly resisted—however weakly—plans to spend more money. But with war cries in their ears and the Huns at the Somme, the peoples’ representatives got in the habit of merely rubber-stamping any request that came their way. They voted for credits of 22,804.5 million francs in 1915—an amount that rose every year, reaching 54,537.1 million in 1918. In practice, the government spent far more than the credits that had been voted, using special accounts that we might call “off budget” accounts similar to those used by the Bush administration to pay for the war in Iraq. In 1920, 30,000 million francs—an amount nearly equal to the nation’s entire prewar debt—passed through the special accounts (see

Figure 5.1

).

Figure 5.1

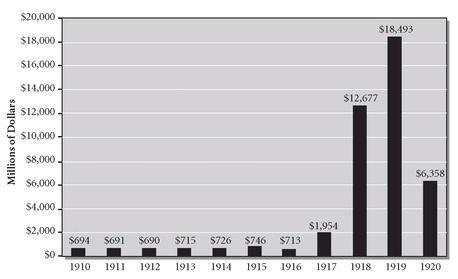

U.S. Federal Outlays, 1910-1920

Woodrow Wilson is best remembered for his desire to “make the world safe for democracy.” However, his involvement in World War I was costly.The one and only respect in which the war paid off was that it turned America into an empire.

Source:

“Historical Table,” Budget of the United States Government.

When America entered the war, its expenditures outdid the other combatants, averaging $42.8 million per day from July 1917 until June 1919. Total federal expenditure rose 2,454 percent in the three years 1916 to 1919. The Federal Reserve issued more and more paper notes; the supply rose by 754 percent between March 1917 and December 1919.The overall money supply increased 60 percent between 1913 and 1918, while GDP increased only 13 percent. The government raised money partly by taxing people much more heavily and partly by borrowing from them. Four “Liberty Loans” were floated during the war years. At the war’s end, a “Victory Loan” was offered.

All of this borrowing, spending, and taxing left the world’s major economies—especially those in Europe—very fragile. After the war was over, they all attempted to return to the prewar gold standard that had worked so well for so long. But they were like the farmers going out to plow their fields in northeastern France; they kept hitting unexploded bombs and blowing themselves up.

Wilson’s meddling was disastrous from practically every point of view—except one.The war continued for another 18 months. Not a single major government in Europe survived in its prewar form. “In 1914, Europe was a single civilized community . . .” wrote A.J.P. Taylor, “A man could travel across the length and breadth of the Continent without a passport until he reached . . . Russia and the Ottoman empire. He could settle in a foreign country for work or leisure without legal formalities. . . . Every currency was as good as gold.”

33

In 1919, European civilization was a wreck, out of which tough new menaces would be hammered—first in Russia, then in Italy and Germany. Nor did any currency buy as much at the end of the war as it did at the beginning.All the principal belligerents, with the exception of the United States, were forced off the gold standard. The one and only respect in which the war paid off was that it turned America into an empire.

And here we pick up the trail and follow the money that leads to America’s empire of debt.

6

The Revolution of 1913 and the Great Depression

Readers of this book will scarcely have given any thought to the fact that they have never lived in the system of government argued for by Madison, Jay, and Hamilton in the Federalist Papers. “It may come as a shock . . .” wrote John Flynn, “to be told that [you] have never experienced that kind of society which [our] ancestors knew as the American Republic . . . .” Flynn, the editor of the popular weekly the Saturday Evening Post, had already come to this conclusion in 1955. In his book

The Decline of the American Republic,

Flynn observed that Americans needlessly “live in the war-torn, debt-ridden, tax-harried wreckage of a once imposing edifice of the free society which arose out of the American Revolution on the foundation of the U.S. Constitution.”

1

An empire needs a source of income sufficient to fund its military campaigns, regulatory regimes, and domestic schemes. It also needs a strong central authority to direct its ambitious new programs. In one short 12-month span, a year the writer Frank Chodorov calls the “Revolution of 1913,” the empire got the tools it needed. That year—the same year European countries abandoned the gold standard in preparation for World War I—the old Republic ceased to exist.

America’s current system of income tax is a twentieth-century invention. Previous attempts at creating a national tax had failed or had been thrown out because they violated tenets of the Constitution deemed essential by the founders. In its first 100 years, the United States supported its federal government with a series of what we would call “sin taxes” today, on whiskey, tobacco, and sugar. By 1817, all internal taxes were abolished by Congress, leaving only tariffs on imported goods as a means for supporting the government.

The first income tax that citizens of the young Republic were forced to endure came about because Congress had been asked to fund the War between the States. In 1862, a tax on incomes between $600 and $10,000 was assessed at the rate of 3 percent, and the Internal Revenue Service (IRS) was created. The war was costing $1.75 million per day.

2

The government sold off land, borrowed heavily, enacted various fees, and increased excise taxes, but it simply wasn’t enough. The income tax seemed like the only way to finance the war and service the country’s then-staggering $505 million debt. That tax was promoted as a temporary wartime measure. Temporary it was. In 1872, after servicing the Reconstruction, Congress yanked the “temporary” tax.

But that was not the end of it. The income tax appealed to empire builders because it alone offered enough cash to finance the enterprise. But it had another appeal—to the larceny and envy in the hearts of ordinary citizens. Following a banking panic in 1893, Senator William Peffer of Kansas, supported the progressive income tax in this way:

Wealth is accumulated in New York, and not because those men are more industrious than we are, not because they are wiser and better, but because they trade, because they buy and sell, because they deal in usury, because they reap in what they have never earned, because they take in and live off what other men earn . . . .The West and the South have made you people rich.

3

That sentiment was puffed up by Nebraska’s bellicose world-improver William Jennings Bryan, who argued against the “equal taxation” requirement in the Constitution, in favor of the current progressive one:

If New York and Massachusetts pay more tax under this law than other states, it will be because they have more taxable incomes within their borders. And why should not those sections pay most which enjoy most?

4

This logic is simple. People who are more productive should be forced to pay a bigger share of their common expenses. But this kind of logic had no place in a free republic where all men were supposedly created equal; if they were equal they could each carry their own share of the burden of central government. Under this new regime, men were no longer equal, but given differing loads to carry based on the whims of elected hacks.

With considerable foresight, one member of the House of Representatives predicted:

The imposition of the [income] tax will corrupt the people. It will bring in its train the spy and the informer. It will necessitate a swarm of officials with inquisitorial powers. It will be a step toward centralization . . . . It breaks another canon of taxation in that it is expensive in its collection and cannot be fairly imposed . . . and, finally, it is contrary to the traditions and principles of republican government.

5

When the tax was again introduced in 1894, a challenge went to the U.S. Supreme Court. In 1895, even among the cacophony of appeals in Congress to “soak the rich,” the Supreme Court declared the bill unconstitutional in a 5-to-4 ruling. In writing the majority opinion, Justice Stephen J. Field quoted another case to support his conclusion:

As stated by counsel:“There is no such thing in the theory of our national government as unlimited power of taxation in congress.There are limitations, as he justly observes, of its powers arising out of the essential nature of all free governments; there are reservations of individual rights, without which society could not exist, and which are respected by every government. The right of taxation is subject to these limitations.”

6

But when the winds of empire blew, the old yellowed paper of the U.S. Constitution went flying. Following The Panic of 1907, President Theodore Roosevelt sided with a faction in the Democratic Party that wanted to amend the Constitution to allow a national income tax. In 1909, President Taft stated that he had “become convinced that a great majority of the people of this country are in favor of vesting the National Government with power to levy an income tax.”

7

Of course, politicians are always able and willing to argue that “the people” want a government to have more power. If the voters see a free lunch in the deal, they’re for it. By 1913, just in time for Wilson’s emergence on the world stage, the Sixteenth Amendment had been ratified by enough states to put the income tax into law.The Amendment states:

The Congress shall have power to lay and collect taxes on incomes, from whatever source derived, without apportionment among the several states, and without regard to any census or enumeration.

8

It wasn’t long before Congress exercised its new powers. Wilson even convened a special session of Congress to rush through the first tax law under the Sixteenth Amendment, in which earnings above $3,000 were subject to a 1 percent tax, gradually moving up to 7 percent on higher income levels.

With its rather modest rates, the original income tax was viewed as a benign inconvenience. As early as 1916, however, the top rate was more than doubled from 7 percent up to 15 percent. Then as cash was needed to send Pershing to France, the rate was hiked to a staggering 67 percent in 1917 and 77 percent by 1918. Even the low rates were raised. From their microscopic origin of only 1 percent, the rate settled into a “modest” 23 percent by the end of World War II. But by that time, the people of the old republic had grown to accept an income tax as a necessary evil. Now that the nation was an empire, it needed the money.