The New Empire of Debt: The Rise and Fall of an Epic Financial Bubble (28 page)

Read The New Empire of Debt: The Rise and Fall of an Epic Financial Bubble Online

Authors: Addison Wiggin,William Bonner,Agora

Tags: #Business & Money, #Economics, #Economic Conditions, #Finance, #Investing, #Professional & Technical, #Accounting & Finance

MacNamara points out that leading intellectuals, the media, politicians, policymakers, and even street bums viewed the war as a struggle between communism and the Free World.

Could not Vietnam have been independent, but neutral in the Cold War? Why did it matter anyway;Vietnam was still a primitive, mostly agricultural nation. Whichever side gained her allegiance, what did they gain? Nobody ever seemed to ask—either themselves or the other side.

“I am aghast at the shallowness of our thinking on the issue of a neutral solution,” writes MacNamara. “Why didn’t we ask Hanoi for a full explanation of the process they foresaw? If we had asked, and if they had convinced us, for example, that they foresaw reunification taking years, even decades, my god, we would have or should have jumped at it.”

21

In the discussions and confessions 30 years after the end of the war, the Vietnamese said they had been open to suggestion. In retrospect, it looks as though the whole conflict—or at least the bloodiest part—could have been avoided, simply by sitting down and exploring a few issues. But the lunkheads running U.S. foreign policy at the time did not even bother to ask. It was arrogance, no doubt, on the part of MacNamara and others, that prevented anyone in the administration from seriously considering

conversation

as an alternative to brute force.

Bad ideas, foolish theories, misconceived campaigns, misunderstood signals—the war in Vietnam began in almost total ignorance and went downhill. Nobody knew anything worth knowing. Nobody understood anything worth understanding. And nobody did anything worth doing.

But we return to the critical question: Americans were dead set against letting Vietnam “go communist.” Why? If a group of people in Columbus, Ohio, decided to pool their property and to live collectively, there would be no terrible outcry. (Though eventually, the Feds would probably get them on a weapons or tax charge.) The only plausible reason for being against communism is that the communists were almost invariably world-improvers themselves. They were not content to collectivize their own property, but insisted on collectivizing other people’s property, too.Then, when they had made a mess of their own country, they turned their sights on the countries next door.

The feature that made communism barbaric was not that people shared the same toothbrush or denied the profit motive. Instead, it was the common mark of all barbarism—the readiness to use brute force to get what you want. What marks a civilized society, on the other hand, is a reluctance to use force, preferring persuasion and cooperation over force and fraud.

There are only two ways to get what you want in life.You can get it honestly, by trade, work, or some other bargain—an economic means of some sort. Or, you can get it dishonestly, by stealing it or taking it away from someone—that is, by political means. There is no other way, save a miracle. This distinction works for “things” such as automobiles and whiskey. It also works for other “wants”—such as sex, ambition, and vanity. We can build our reputations and our own

amour propre

by economic means; say, by working hard we can earn money and feel superior to others. Or we can pick a fight with others to prove we can beat them. Into which category does the effort to “bomb North Vietnam back to the Stone Age” fit? American involvement in Vietnam may have been well-intentioned, but it was missing the point.

Martin Luther King confronted the contradiction in a famous speech. “My opposition to the war,” he said:

. . . grows out of my experience in the ghettoes of the North over the last three years—especially the last three summers. As I have walked among the desperate, rejected and angry young men I have told them that Molotov cocktails and rifles would not solve their problems. I have tried to offer them my deepest compassion while maintaining my conviction that social change comes most meaningfully through nonviolent action. But they asked—and rightly so—what about Vietnam? They asked if our own nation wasn’t using massive doses of violence to solve its problems, to bring about the changes it wanted. Their questions hit home, and I knew that I could never again raise my voice against the violence of the oppressed in the ghettos without having first spoken clearly to the greatest purveyor of violence in the world today—my own government. For the sake of those boys, for the sake of this government, for the sake of hundreds of thousands trembling under our violence, I cannot be silent.

22

If Western democracies have a virtue, it is that they are gradual and consensual—that is to say, that they are civilized. If suddenly the majority of Americans were to decide that every citizen with red hair should be guillotined, it would be an uncivilized thing to do—even if they had voted on it fair and square. It is the means that are the end.The fact that people are willing to get along with one another without resort to violence is what makes a civilized society, not the fact that the particular day-to-day whims of the masses are enacted into law by a group of legislative hacks. Defending Western civilization by bombing North Vietnam was a bit like what Clovis, King of the Francs, proposed to do after he had become a Christian and learned of Christ’s crucifixion. Legend has it that Clovis remarked: “If only I had been there with my armies, I would have had revenge against those Jews.”

In his private life, Lyndon Johnson understood what the Vietnam War really meant for America:

I don’t think it’s worth fighting for and I don’t think we can get out. It’s just the biggest damned mess I ever saw . . . . And we just got to think about—I was looking at this sergeant of mine this morning. Got six little kids . . . and he bringing me my things and bringing me my night reading . . . and I just thought about ordering his kids in there and what in the hell am I ordering him out there for? What the hell is Vietnam worth to me? What is Laos worth to me? What is it worth to this country? No, we’ve got a treaty, but, hell, everybody’s got a treaty out there and they’re not doing anything about it.

23

But America went in anyway. And then the bodies came back in plastic bags.

And even after 30 years, it seems not to have occurred to MacNamara that he did anything wrong. Right and wrong seemed to have no place in his analytical brain. Instead, he wondered how he could have done his job better, how he could have fought the war more efficiently, or why he “missed opportunities” to settle it at lower cost. He saw no moral lessons—only practical ones. He looked for no wisdom from the dead, only hints from the living about how to win. If he had only had more information, says MacNamara, his world improvements would have turned out better.

Tran Quang Co put him on the spot:

Mr. MacNamara admits his mistakes, which we admire, but he unfortunately attributes most mistakes to misjudgments and miscalculations. But we must also ask: What about values and intentions? As I understand it, the right to self-determination—the independence of a nation—belongs to the general values of the world community. What about U.S. support of the French colonialists after World War II, in defiance of its own democratic traditions? What about the direct U.S. military intervention in Vietnam—I mean sending U.S. soldiers to find and kill Southern Vietnamese? And what about the U.S. policy seeking to divide Vietnam for good and to “bomb North Vietnam back to the Stone Age?” We must ask: are these policies consistent with the moral values?

24

Principles? Morals? There is no room for constitutional restraints, authentic values, or real virtues when you are building an empire.The heart overpowers the brain. Public chatter overpowers private thoughts. Public slogans drown out private acts of decency and courage. Empty words and big theories replace actual thinking.The public itself is charmed and bamboozled, then robbed, killed, or both.

Americans learned nothing from the French experience. De Gaulle warned Kennedy that Vietnam would be a graveyard for American soldiers. It was a “rotten country,” he said, unsuitable for Western ways of war. But in the inflationary boom of the first “Guns and Butter” administration, that of Lyndon B. Johnson, Americans thought they could do what the French couldn’t. They spent far more money than the French and lost far more men, but Giap beat them, just as he had the French.

While France and America enjoyed their defeats, Vietnam suffered its own dreary independence like a war wound. The whole country oozed a pathetic poverty for the next quarter century, scabbed over with a squalid ideology.

As of 2005, General Giap was still alive.The old man, 91 when he was interviewed by the

Figaro

in 2004, was asked what he thought of America’s situation in Iraq: “When you try to impose your will on a foreign nation you will be defeated. Every nation that struggles for independence will win.” Woe to empires.

“What we’ve done,” continued the old man, perhaps drifting into senile dementia, forgetting that his comrades set up a police state following his military victory, “was to fight for the right of each man to live and develop as he chooses . . . and the right of each people to enjoy national sovereignty.”

8

Nixon’s the One

On August 15, 1971, the administration of Richard Milhous Nixon did something extraordinary. It slammed the “gold window” shut. Henceforth, foreign governments would not be able to redeem their surplus U.S. dollars for gold.

Mention the late president’s name, and the average person recalls the crime with which he is so often associated: B&E (breaking and entering) at the Watergate. But while the public’s attention was distracted by Nixon’s fumbling sidekicks, another team of Nixon goons was pulling off the biggest heist of all time.

A lumpen investor, a university economist, or a Federal Reserve governor might have read the headlines of the past 30 years without noticing how they tucked together. He might have seen the boom in gold of the 1970s, the bubble in Japan in the 1980s, or the subsequent bubbles throughout the rest of Asia as events as independent of each other as a stolen hub-cap in New Orleans and a stolen kiss in Boston.

He might also have looked on the boom and bubble in the United States as unrelated and mistaken the run-up in stock prices as a consequence of the New Era wonder age, the new productivity of information age technology, or the newfound wisdom of the guiding hands at the Federal Reserve. He may even have referred to the productivity miracle as the source of such a wonderful thing. Never, on the other hand, would he have imagined that all the great economic and market events of the past three decades found their inspiration in the same place and time: at the hands of Nixon’s henchmen in the early 1970s.

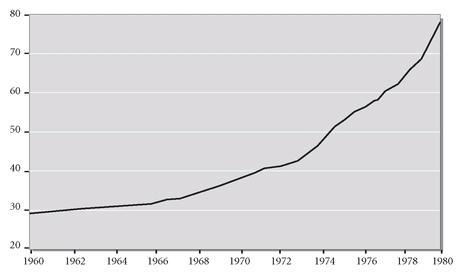

Figure 8.1

Consumer Price Index, 1960-1980

Richard Nixon’s decision to slam the “gold window” shut has had one demonstrable effect: It set in motion the worldwide credit bubble of the pax dollarium age. As a result, the price Americans have to pay for “goods and services” has risen dramatically—and without a pause—ever since.

Source:

Bureau of Labor Statistics.

What was their crime? Breach of contract? Theft? Fraud? Counterfeiting? It was all those things.They breached the solemn promise of five generations of U.S. Treasury officials and set in motion the worldwide credit bubble of the pax dollarium age (see

Figure 8.1

).

In 1971, the decision to abandon the gold standard was not exactly an improvisation. The decision was part of a series of moves made by the Nixon administration to hold down wages and prices and to check inflation. Consumer prices rose at 4.9 percent in 1970 and inflation looked as though it was going to get worse. Nixon came to believe that he could control the economy, even though this shift in policy contradicted his own political and economic philosophy as stated in the past.

Arthur Burns, chairman of the Federal Reserve during Nixon’s administration, had served as an advisor during Nixon’s failed 1960 presidential campaign. At that time, Burns warned Nixon that tight money policies would worsen the economy, hurting Nixon and ultimately costing him the election. Burns proved to be right:

Now, a decade later, in May 1970, Burns stood up and declared that he had changed his mind about economic policy. The economy was no longer operating as it used to, owing to the now much more powerful position of corporations and labor unions, which together were driving up both wages and prices. The traditional fiscal and monetary policies were now seen as inadequate. His solution: a wage-price review board, composed of distinguished citizens, who would pass judgment on major wage and price increases.Their power, in Burns’s new lexicon, would be limited to persuasion, friendly or otherwise.

1

Nixon agreed with most of it, except the part about limiting controls to friendly persuasion.