The New Empire of Debt: The Rise and Fall of an Epic Financial Bubble (35 page)

Read The New Empire of Debt: The Rise and Fall of an Epic Financial Bubble Online

Authors: Addison Wiggin,William Bonner,Agora

Tags: #Business & Money, #Economics, #Economic Conditions, #Finance, #Investing, #Professional & Technical, #Accounting & Finance

Every level colluded with every other level to keep the flimflam going. On the banks of the Potomac, people of all classes, rank, and station were pleased to believe that all was well. And there, at the Federal Reserve headquarters, was another caste of loyal liars. Alan Greenspan and his fellow connivers not only urgd citizens to mortgage their houses, buy SUVs, and commit other acts of wanton recklessness, they also controled the nation’s money and made sure that it played along with the fraud.

From the center to the furthest garrisons on the periphery, from the lowest rank to the highest—everyone, everywhere willingly, happily, and proudly participated in one of the greatest deceits of all time.At the bottom of the empire were wage slaves squandering borrowed money on imported doodads. The plebes gambled on adjustable rate mortgages (ARMs). The patricians gambled on hedge funds that speculated on huge swaths of mortgage debt. Near the top were Fed economists urging them to do it! And at the very pinnacle was a chief executive, modeled after whom . . . Augustus or Commodus? . . . . who cut taxes while increasing spending on bread, circuses, and peripheral wars.

The spectacle was breathtaking. And endlessly entertaining. We were humbled by the majesty of it. Everywhere we looked, we saw an exquisite but precarious balance between things that were equally and oppositely absurd.

On the one side of the globe—in the Anglo-Saxon countries in general, but the United States in particular—were the consumers.On the other side—principally in Asia—were the producers. One side made, the other took. One saved, the other borrowed. One produced, the other consumed.

This is not the way it was meant to be. When America first stooped to Empire, she was a rising, robust, energetic, innovative young economy. And for the first six decades of her imperium—roughly from 1913 until 1977—she profited from her competitive position. Every country to which she was able to extend her pax dollarum became a customer. Her businesses made a profit.

But gradually, her commercial advantage faded and her industries aged. The very process of spreading the soft warmth of her protection over the earth seemed to make it more fertile. Tough, weedy competitors sprouted all over the periphery of the empire—first in Europe, then in Japan, and later, throughout Asia, even areas she had never been able to dominate.

By the early twenty-first century, the costs of maintaining her role as the world’s only superpower, and its only imperial power, had risen in excess of 5 percent of her GDP, or $558 billion per year. Not only had she never figured out a good way to charge for providing the world with order, now order was working against her. The periphery economies grew faster. They had newer and better industries. They had higher savings levels and much lower labor rates. They had few of the costs of bread or circuses and none of the costs of policing the empire.They were freer, lighter, faster. Every day, the competitors took more of America’s business, assets, and money. If the empire were an operating business, accountants would say it was losing money.

The empire no longer pays because the entire Western world—including Japan—has lost its competitive edge. Globalization of the pax dollarum era served the United States well after World War II. America was the world’s leading exporter. But Europe also thrived in the 30 years after the war—

les trente glorieuses,

as the French call them. Then, in the 1980s, the Japanese took over as the leading economy of the advanced world.

And now, the pax wrought by the American empire works against America. Asian factories are newer and more modern. Asian workers are younger and cheaper. Now, every business day that passes, the Asians grab a little more of the U.S. market. And every business day puts Americans $2 billion further beholden to its mostly Asian creditors.

“GM plans to cut 25,000 jobs in the U.S.” The headline appeared on the front page of the

International Herald Tribune

in mid-June 2005. Elsewhere in the paper was a status report explaining that China’s Chery Automobiles planned to begin exporting the first of 250,000 Chery Crossovers to the United States in 2007. For every job lost by America’s preeminent industrial company, China was planning to export 10 new cars. Scarcely a year later, at the end of 2008, China was actively considering buying all three of America’s automakers.

It was not just manufacturing that was moving to periphery states.The advent of high-speed, inexpensive communications, along with cheap computing power, allowed Asians to compete in service sectors as well. Anything that can be digitized can be globalized—architecture, law, accounting, administration, data processing of all sorts, call centers, record keeping, marketing, publishing, finance, and so forth.

What was left for the developed economies? What could they do? Here is where European and Anglo-Saxon economies parted company. The Europeans emphasized high value-added products such as luxury goods and precision tools. They clung rigidly to the wisdom of the old economists, refusing to expand consumer credit and refusing to use massive doses of fiscal stimuli to increase overall demand. House prices rose sharply in Paris, Madrid, and Rome. But there were few signs of speculation. Houses were not refinanced readily. They were not “flipped.” There was little creative finance. Nor was there a big run-up in consumer debt, or a big run-down in savings rates. Credit cards were still comparatively rare. Unemployment was high, for Europe’s policy managers tolerated neither marginal jobs nor marginal credits. Europe was rigid and dull, economically, but relatively solid, with a positive balance of trade.

The Anglo-Saxon countries took a different route. During a time when the Bank of England has regularly moved interest rates up and down to deal with changes in economic conditions, the ECB sat on its hands.

The general consensus was that Europe would be better off if it acted a bit more like the Anglo-Saxons, by manipulating interest rates to encourage consumer debt. American economists imagined themselves carefully analyzing the data and coming to a logical conclusion.What they did not realize was that their numbers, conclusions, and views of the world had become nothing more than stones in the immense pyramid of

consuetude fraudium

of the advanced empire.

The numbers were frauds. If you were to look at the percentages fairly, the European economy actually looked no worse than its Anglo-Saxon competitor—with a similar rate of growth, higher unemployment, but better productivity and less debt.

As the Anglo-Saxon economies lost their competitive edge in manufacturing, they tried to make up for it by encouraging consumption. This was the biggest fraud of all. At first, higher consumption feels good. It is like burning the furniture to keep warm; it feels good for a moment. But the sense of well-being is extremely short-lived. When people borrow and spend, they feel as though they are getting richer—especially when their houses are rising in price.The increased consumption even shows up, indirectly, in the GDP figures as growth. But you don’t really become wealthier by consuming. You become wealthier by making things you can sell to others—at a profit.The point is obvious but, at this stage of imperial finance, it was inconvenient.

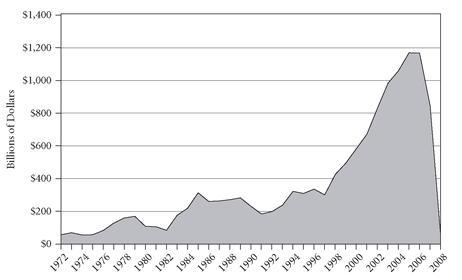

The homeland’s losses—measured by a negative balance of trade—began in the mid-1970s. Less than 30 years later, both government and consumers were running up debts at an alarming rate. What else could they do? The only way Americans could continue their imperial role—which meant more to them than ever, since it was now the only source of national pride left to them—was to borrow (see

Figures 10.1

and

10.2

).

Figure 10.1

New Borrowing by Federal Government

The homeland’s losses—measured by a negative balance of trade—began in the mid-1970s. Less than 30 years later, both the government and consumers were running up debts at an alarming rate.The only way American’s could continue their imperial role was to borrow.

Source:

Federal Reserve.

Figure 10.2

New Borrowing by Private Households

Source:

Federal Reserve.

The global economic system in the pax dollarium era was perfectly balanced. For every credit in Asia, there was an equal and opposite debit in the United States. And for every dollar’s worth of demand from the United States, there was a dollar’s worth of supply already waiting in a container in Hong Kong.

But while the imperial finance system was flawless, its perfections were devastating.

In mid-2005, Americans saluted their imperial standards. They gratefully pasted the flag to their car windows, their jackets, their hats, their beer mugs, their shirts, and even their underwear (never once in Europe have we seen anyone with a national flag anywhere except at a parade or a public building). Americans are proud of their empire—and should be. Without it, they could never have gotten so far in debt. What central banker would fill his vault with Argentine pesos or Zimbabwe dollars? What drug dealer or arms seller would want Polish zlotys in payment? What insurance company would want to buy Bolivian or Kyrgzstan bonds to cover its long-dated liabilities? The dollar has not been convertible into gold for 37 years.Yet, people still take it as though it were as good as the yellow metal—only better. Ultimately, lending money to a foreign government is a bet that the government will put the squeeze on its own citizens to make sure you get paid. The United States doesn’t even have to squeeze.When one foreign loan comes due, other foreigners practically line up to refinance it; it is as if they were offering free drinks to a street bum, just to gawk and wonder when he might pass out.

“Since Prime Minister Sir Robert Walpole’s introduction of the funding system in England during the 1720s,” writes H.-A. Scott Trask for the Mises Institute, “the secret was out that government debt need never be repaid . . . .Walpole’s system proved its worth in financing British overseas expansion and imperial wars in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries. The government could now maintain a huge peacetime naval and military establishment, readily fund new wars, and need not retrench afterward.The British Empire was built on more than the blood of its soldiers and sailors; it was built on debt.”

2

The new system was slow to catch on in America. Jefferson was against it. In 1789, in a letter to James Madison, he wondered whether “one generation of men has a right to bind another.” His answer was “no.”“The earth belongs in usufruct to the living,” he concluded. “No generation can contract debts greater than may be paid during the course of its own existence.”

3

An intergenerational debt is an odd thing. Say a man buys a house. He may leave the house to his children, with a mortgage owing. The children were not party to the mortgage contract, but they take the bequest in good grace.

The house may have a mortgage or it may need a new roof. A gift is a gift, encumbered or not. If it is too heavily burdened with debt, they could simply turn it down; they never made a deal with the mortgage company and are under no obligation to pay it.

Suppose it is credit card debt. Say the man used the money to take a trip around the world. But the trip wore him out; no sooner does he return home than he collapses of a heart attack.Are the children under any obligation to pay the credit card bills? Not at all.

But comes now, “public” debt. What kind of strange beast is this? One generation consumes. It then hands the next generation the bill.The younger generation never agreed to the terms of the indebtedness. They are party to a contract—and on the wrong end of it, we might add—that they never made. Indentured servants only had to work seven years to pay off their indenture. This new generation, on the other hand, will have to work their entire lives.

Such arrangements are often excused as part of the “social contract.” But what kind of contract allows one person to take the benefits while sticking the costs to someone else?