The New Policeman (10 page)

Authors: Kate Thompson

It ought to have taken him at least half an hour to walk to the village from where he started out, but when he got to the main road his watch was still saying five thirty-five. He shook it and held it up to his ear. Silence. A single tick. More silence. He

pressed all the buttons, trying all the different time zones, pulling and pushing on the tiny dials that set the hands and the alarm. Nothing made any difference. He could see the second hand moving, but absurdly slowly; a single, jerky step, then nothing, then another one. J.J. tried to work up some annoyance at it, but he couldn’t. What did it matter if his watch had stopped? What was the rush, anyway?

He walked on, and arrived at the edge of the village. His village. It was certainly Kinvara, but at the same time it wasn’t. A pair of metal water pumps, painted yellow and blue, stood where MacMahon’s filling station ought to be. Opposite it, the same line of sturdy trees leaned over the high stone wall, but behind them, in place of the church, was a massive outcrop of gray rock with circles and spirals carved into its walls. Scrubby bushes and ferns grew out of its crevices. J.J. moved on, preferring not to dwell upon who, or what, might be worshipped in such an edifice.

The same streets ran through the village in the same directions. It had the same corners and crossroads as far as he could see, but the streets were cobbled instead of paved, and the houses that lined them were similar to those he had already passed. They

leaned against one another at all kinds of odd angles, not one of them in proper alignment with its neighbor, but all of them somehow relaxed and comfortable with the arrangements. All of them, as far as J.J. could ascertain, were empty. Where was everyone?

J.J. listened. There was no wind. He caught glimpses of the sea as he passed the side streets that ran down to it at right angles to the main street, but he couldn’t hear it. Its surface was like glass. The air was too still for there to be any waves. But he could, or he imagined he could, hear something else. The faint strains of music drifting up the street toward him.

He walked on, heading toward it. As he did so, he saw a movement in the shadows against the wall. A large gray dog that he hadn’t noticed before stood up. It was directly in J.J.’s path. He crossed to the other side of the street, but the dog moved out from the wall to intercept his path. Even from a distance he could see that the creature was in a very bad way. It was walking on three legs. The fourth, one of the hind legs, was partially severed at the hock, and what was left of it was dragging along behind. J.J. shuddered. The dreadful sight cast the first damper on his experience of Tír na n’Óg and made him wonder what

other horrors it might be holding in store for him.

He stopped in the middle of the street. The dog was huge. Its wiry coat and long, fine muzzle gave it the appearance of an Irish wolfhound, but it was much broader and heavier than any J.J. had seen. He watched as it approached, ready to run if it showed any hint of aggression. It didn’t. Its demeanor was benign; almost servile. J.J. stood his ground and waited as it came right up to him and sniffed at his hand. Then he reached out and stroked its head.

The injury, when J.J. bent down to inspect it more closely, was truly horrendous. The lower part of the leg was hanging on by a thin cord of skin and sinew. Bone showed through on both parts of the leg. A drop of blood fell from it and soaked into the dust.

“You poor thing,” said J.J. “What on earth happened to you?”

As if in answer, the dog suddenly pricked its ears and turned to look back down the street. A brown goat was tearing up toward them, closely followed by a large, bearded man.

“Stop her!” he yelled at J.J.J.J. spread his arms and barred the goat’s path. She dodged to the left, but J.J. was well accustomed to

goat behavior and had anticipated her. Again he barred her path, and this time she checked and doubled back, straight into the arms of her pursuer.

“Good man,” he said. “She’s an awful wagon, so she is.”

The goat let out a plaintive bleat and struggled, but the man had a firm grip on one of her horns and he wasn’t about to lose her again. “Come on down to the quay,” he said to J.J. “Everybody’s down there.”

“I just found this dog,” said J.J.

“Oh, yes,” said the man. “That’s Bran.”

“She’s had an awful accident,” said J.J.

“’Twas a fight, I’d say,” said the man. “Poor old Bran.”

He began to walk back down the hill, dragging the struggling goat behind him.

“We can’t just leave her,” said J.J.

“Don’t mind her,” said the man. “She’ll probably follow us down.”

J.J. watched him as he turned the bend in the street and went out of sight. He was standing just a few feet away from the vet’s office, but it looked, in this Kinvara, just like an ordinary house. He glanced across the street to where Séadna Tobín’s pharmacy would have been standing in his world. It seemed a bit more

hopeful. Perhaps someone there could tell him where to find the vet?

The door, like all the doors in the street, stood wide open. J.J. stood beside it and listened. There were people in there, somewhere at the very back of the shop. They seemed to be having an argument, though, from the sound of it, and J.J. was reluctant to knock. Perhaps the best thing would be to go down to the quay and see if there was anyone there who could help.

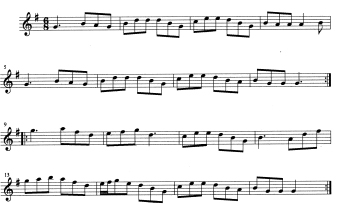

THE BIG BOW-WOW

Trad

“Did you pass J.J. on the road?” Helen asked Phil when he arrived for the céilí.

“No,” said Phil. “Isn’t he here?”

Helen shook her head. “He’ll probably be here in a minute.”

Phil unlatched his case and took out the guitar. “I didn’t track down our policeman either,” he said. “No one seems to know where he lives. I suppose he hasn’t been here long enough.”

Helen glanced toward the door. Her mind was not on the policeman. “Shame,” she said.

“We’re sure to run into him before the next one,” said Phil. “If he turns up in Green’s again I’ll give you a shout, will I?”

“Worth a try, I suppose,” said Helen.

“The next time he comes with his fiddle, that is,” said Phil. “Not the next time he takes our names.”

The dancers were drifting in, two or three at a time, and wandering toward the makeshift bar. Helen put down the concertina and made her way over to the door. Night had fallen. She looked out into the dark yard, already full of parked cars. Another group of dancers was arriving.

“You didn’t pass J.J. on the road, I suppose?” she asked them.

Anne Korff had just finished letting the air out of J.J.’s front tire when the phone rang. By her watch it was nearly ten o’clock. She lifted the receiver. It was, as she had suspected it might be, Helen Liddy. Anne listened, then said, “Yes. He dropped in the cheese, but that was a good while ago now. Maybe five o’clock or so.”

“Did he say where he was going?”

“I don’t think so,” said Anne, quite truthfully. “He was mostly concerned with your birthday present.”

“My birthday present?”

“Something he wanted to buy for you.”

“Oh,” said Helen. “He said he was going to see

Jimmy Dowling, but there’s no answer there. Maybe he called in on someone else.”

“Maybe,” said Anne. “He left his bike here, you know. It had a puncture. I offered to give him a lift, but he said he wouldn’t take it.”

“Oh, maybe that’s it,” said Helen. She sounded relieved. “He’s probably getting a lift up with someone.”

She rang off, and Anne sat down heavily on the nearest chair. Distressing J.J.’s parents hadn’t been part of the plan. Now that she thought about it, there hadn’t really been a plan at all. She should probably go and get J.J. back before Helen got any more worried. But on the other hand, if J.J. did somehow succeed in getting her the birthday present she had asked for, she would be more than compensated. Perhaps a bit longer wouldn’t do too much harm.

Helen returned to the céilí. The dancers were still standing around the bar, waiting for the music to start. Marian, who was always in big demand as a dancing partner, disengaged herself from the set that had nabbed her and came over.

“You all right, Mum?”

“I’m just worried about J.J.”

“Don’t,” said Marian. “He’s well able to look after himself. He won’t do anything stupid.”

“I suppose so,” said Helen. “I just can’t understand where he could be.”

“Didn’t he tell you?” said Marian. “The rotten sod.”

“Tell me what?”

“He’s gone clubbing in Gort.”

“Clubbing?”

“Yeah. They had it all planned. He’s staying the night at Jimmy Dowling’s house. I can’t believe he just went. He promised me he’d tell you.”

THE EAVESDROPPER

Trad

The dog limped painfully behind J.J. as he walked down toward the quay. At the foot of the hill the main street formed one edge of an open triangular area. The second side was another row of squodgy houses, and the third was the harbor wall. In this space, the residents of the village had gathered together to dance beneath the open sky.

To J.J.’s disappointment, they appeared to be neither leprechauns nor gods. The clothes they were wearing were representative of the changing fashions of several centuries, giving J.J. the vague impression that he had stumbled upon some kind of fancy dress party. Other than that the people on the quay appeared little different from the population of any Irish village.

The doors of the three nearest pubs were open. In his village they were called Green’s, Connolly’s and Sexton’s, but here they had no names; not written above their doors, anyway. Those people who were not dancing lounged against their walls or sat on benches or on the curb of the footpath, holding goblets and tankards, and pint glasses of what looked to J.J. suspiciously like draft Guinness.

No one took any notice of him. The dog detached herself from him and parked herself on the footpath between the wall of Connolly’s and the arrangement of chairs, barrels, and upturned buckets where the musicians were seated. J.J. leaned against the corner and observed them from behind. There were six of them: two fiddlers, a piper, a whistle and a flute player, and, playing the bodhrán, the bearded man that J.J. had encountered chasing the goat. They were in the middle of a set of reels. J.J. knew the tune they were playing, or a version of it, but he couldn’t think of its name. They weren’t playing particularly fast, but the rhythm, the lift in the music was electrifying. It made J.J.’s feet itch to dance.

The dancers didn’t form sets, like they did at the Liddy céilís, but nor did they dance alone, like the step or sean nós dancers at fleadhs. In some

way the whole gathering contrived to dance both separately and together, interacting with one another now and again, then disengaging to form part of the bigger, and somehow perfectly circular, whole. Their footwork was spectacular; both energetic and graceful. Their bodies seemed to be as light as air.

Far too soon for J.J. the set of tunes came to an end. The dancers drifted apart, laughing, adjusting their clothing or their hair. Some of them made for the pubs, others stood around and talked or flirted with one another. Some of the musicians got up as well, and as they did so they noticed him leaning against the wall. There was a brief discussion among them, then one of the fiddle players, a fair-haired young man with a winning smile, beckoned to him.

“You’re welcome,” he said, guiding J.J. into an empty seat. “I haven’t seen you around here before.”

“I haven’t been here before,” said J.J.

“You’re all the more welcome, so,” said the fiddler. “We don’t see many new faces. What’s your name?”

“J.J.”

The young man introduced the musicians. The piper was called Cormac, the whistle and flute players were Jennie and Marcus, and the bodhrán player, the

goat chaser, was Devaney. The other fiddle player, who didn’t shake J.J.’s hand because she appeared to be asleep, was called Maggie.