The Next Decade (23 page)

Both world wars were launched according to a single scenario: Germany, insecure because of its geographical position, swept across France in a lightning attack. The goal in both cases was to defeat France quickly, then deal with Russia. In 1914, the Germans failed to defeat France quickly, the troops dug in, and the conflict became a protracted war. The Germans found themselves fighting France, Britain, and Russia simultaneously in both the east and the west. At the same time that it appeared the Bolshevik revolution would save Germany by taking Russia out of the war, the United States sent troops to Europe, playing its first major role on the world stage and blocking German ambitions.

In 1940 Germany succeeded in overrunning France, only to discover that it still could not defeat the Soviet Union. One reason for that was the second act of America’s dramatic emergence. The United States provided aid to the Soviets that kept them in the war until the Anglo-American invasion of France three years later could help destroy Germany for the second time in a quarter century.

Germany emerged from World War II humiliated by defeat but also morally humiliated by its unprecedented barbarism, having committed atrocities that had nothing to do with the necessities of geopolitics. Germany was divided and occupied by the victors.

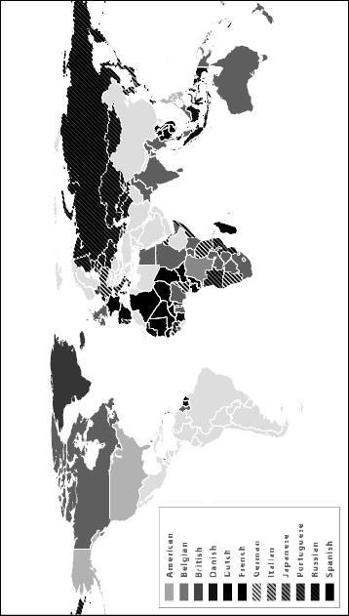

Germany was physically devastated, but its actions had resulted in the devastation of something far more important. For five hundred years, Europe had dominated the world. Before the wave of self-destruction that began in August 1914, Europe directly controlled vast areas of Asia and Africa and indirectly dominated much of the rest of the planet. Tiny countries like Belgium and the Netherlands controlled areas as vast as the Congo or today’s Indonesia.

The wars that followed the creation of Germany destroyed these empires. In addition, the slaughter of the two wars, the destruction of generations of workers and extraordinary amounts of capital, left Europe exhausted. Its empires dissolved into fragments to be fought over by the only two countries that emerged from the conflict with the power and interest to compete for what was left, the United States and the Soviet Union. However, both primarily pursued the fragments of empire as a system of alliances and commercial relations rather than formal imperial domination.

Europe went from being the center of a world empire to being the potential battleground for a third world war. At the heart of the Cold War was the fear that the Soviets, having marched into the center of Germany, would seize the rest of the continent. For Western Europe, the danger was obvious. For the United States, the greatest threat was that Soviet manpower and resources would be combined with European industrialism and technology to create a power potentially greater than the U.S. Fearing the threat to its interests, the United States focused on containing the Soviet Union around its periphery, including Europe.

Two issues converged, setting the stage for the events that will be played out over the next ten years. The first was the question of Germany’s role in Europe, which ever since its nineteenth-century unification had been to trigger wars. The second was the shrinking of European power. By the end of the 1960s, not a single European country save the Soviet Union was genuinely global. All the rest had been reduced to regional powers, in a region where their collective power was dwarfed by the power of the Soviet Union and the United States. If Germany had to find a new place in Europe, Europe had to find its new place in the world.

Empires—1900

The two World Wars and the dramatic reduction of status that followed had a profound psychological impact on Europe. Germany entered a period of deep self-loathing, and the rest of Europe seemed torn between nostalgia for its lost colonies and relief that the burdens of empire and even genuine sovereignty had been lifted from it. Along with European exhaustion came European weakness, but some of the trappings of great-power status remained, symbolized by permanent seats for Britain and France on the United Nations Security Council. But even the possession of nuclear weapons by some of these nations meant little. Europe was trapped in the force field created by the two superpowers.

The German response to its diminished position was in microcosm the European response: Germany recognized its fundamental problem as being that of an independent actor trapped between potentially hostile powers. The threat from the Soviet Union was fixed. However, if Germany could redefine its relationship with France, and through that with the rest of Europe, it would no longer be caught in the middle. For Germany, the solution was to become integrated with the rest of Europe, and particularly with France.

For Europe as a whole, integration was a foregone conclusion—in one sense imposed by the Soviet threat, in another by pressure from the United States. The American strategy for resisting the Soviets was to organize its European allies to defend themselves if necessary, all the while guaranteeing their security with troops already deployed to the continent. There was also the promise of more troops if war broke out, and ultimately the promise to use nuclear weapons if absolutely necessary. The nuclear weapons, however, would be kept under American control. Conventional forces would be organized into a joint command, within the North Atlantic Treaty Organization. This organization created a multilateral, unified defense force for Europe that was, in effect, controlled by the United States.

The Americans also had a vested interest in European prosperity. Through the Marshall Plan and other mechanisms, the United States created a favorable environment in which to revive the European economy while also creating the foundations for a European military capability. The more prosperity was generated through association with the United States, the more attractive membership in NATO became. The greater the contrast was between living conditions in the Soviet bloc and in Western Europe, the more likely that contrast was to generate unrest in the east. The United States believed ideologically and practically in free trade, but more than that, it wanted to see greater integration among the European economies, both for its own sake and to bind the potentially fractious alliance together.

The Americans saw a European economic union as a buttress for NATO. The Europeans saw it as a way not only to recover from the war but to find a place for themselves in a world that had reduced them to the status of regional powers at best. Power, if there was any to be regained, was to be found in some sort of federation. This was the only way to create a balance between Europe and the two superpowers. Such a federation would also solve the German problem by integrating Germany with Europe, making the extraordinary German economic machine a part of the European system. One of the key issues for the next ten years is whether the United States will continue to view European integration in the same way.

In 1992 the Maastricht Treaty established the European Union, but the concept was in fact an old European dream. Its antecedents reach back to the early 1950s and the European Steel and Coal Community, a narrowly focused entity whose leaders spoke of it even then as the foundation for a European federation.

It is coincidental but extremely important that while the EU idea originated during the Cold War, it emerged as a response to the Cold War’s end. In the west, the overwhelming presence of NATO and its controls over defense and foreign policy loosened dramatically. In the east, the fall of the Berlin Wall and the collapse of the Soviet Union found sovereign nations coming out of the shadows. It was at this point that Europe regained the sovereignty it had lost but that it is now struggling to define.

The EU was envisioned to serve two purposes. The first was the integration of western Europe into a limited federation, solving the problem of Germany by binding it together with France, thereby limiting the threat of war. The second was the creation of a vehicle for the reintegration of eastern Europe into the European community. The EU turned from a Cold War institution serving western Europe in the context of east-west tensions into a post–Cold War institution designed to bind together both parts of Europe. In addition, it was seen as a step toward returning Europe to its prior position as global power—if not as individual nations, then as a collective equal to the United States. And it is in this ambition that the EU has run into trouble.

THE CRISIS OF THE EU

In the late eighteenth century, when thirteen newly liberated British colonies formed a North American confederation, it was as a practical solution to economic and political issues. But the United States of America, as that confederation came to be known, was also seen as a moral mission dedicated to higher truths, including the idea “that all men are created equal and that they are endowed by their creator with certain inalienable rights.” The United States was also rooted in the idea that with the benefits of liberal society came risks and obligations. As Benjamin Franklin put it, “They who can give up essential liberty to obtain a little temporary safety, deserve neither liberty nor safety.” In the United States, with such sentiments at its core, the themes of material comfort and moral purpose went hand in hand.

The United States was also created as a federation of what might be called independent countries, sharing a common language but profoundly different in other ways. When those differences led to secession, most of the remaining states of the United States waged war to preserve the Union. That willingness to sacrifice would have been impossible unless the United States was seen as a moral as well as a practical project.

In the United States, the Civil War established that the federal government was sovereign, and absolutely sovereign in foreign affairs. The federal victory put to rest the claims of the Confederate states that sovereignty rested with each of them individually.

In the European Union, by contrast, the confederate model is still in place, and sovereignty rests with each individual nation-state. Even at the level of its most basic premise, then, the European Union sets severe limits on its claims to authority and its right to command sacrifice. This union is stranger still, in that not all Europe is part of it. Some of its members share a currency; others don’t. There is no unified defense policy, much less a European army. Moreover, each of the constituent nations has its own history, unique identity, and individual relationship to the idea of sacrifice. The military authority to act internationally, an indispensable part of global power, is also retained by the individual states. The EU remains an elective relationship, created for the convenience of its members, and if it becomes inconvenient, nations can leave. There is no bar on withdrawal.

Fundamentally, the EU is an economic union, and economics, unlike defense, is a means for maximizing prosperity. This limitation means that sacrificing safety for a higher purpose is a contradiction in terms, because the European Union has conflated safety and well-being as its moral purpose. There is simply no basis for the kind of inspiring rhetoric that could induce anyone to fight and die to preserve the ideals of the European Union.

As we look toward the decade ahead, the delicate balance of power established to contain Germany is coming apart—not because Germany wants it to, but because circumstances have changed dramatically.

The dissolution started during the financial crisis of 2008. Germany had been one of the leading economic powers since the 1960s, when the western portion successfully emerged from the devastation of World War II. The collapse of communism in 1989 forced the prosperous west to assimilate the impoverished east, an economic liability. While this was painful, over the next decade Germany absorbed its poor remnant and remained the most powerful country in Europe, content with the economic and political arrangements of the EU. Germany was its leading power, yet still one of many. It had no appetite for further dominance, nor any need for it.

When the financial crisis of 2008 hit, Germany suffered, as did others, but its economy was robust enough to roll with the shock. The first wave of devastation was most severe in eastern Europe, the region that had only recently emerged from Soviet domination. The banking system of many of the countries there had been created or acquired by western European countries, particularly banks in Austria, Sweden, and Italy, but also by some German banks. In one country, the Czech Republic, the banking system was 96 percent owned by other European countries. Given that the EU had accepted many of these countries—the Czech Republic, Poland, Slovakia, Hungary, Romania, and Bulgaria, as well as the Baltic nation-states of Latvia, Lithuania, and Estonia—there seemed to be no reason to be troubled by this. But although these eastern European countries were part of the EU, they still had their own currencies. Those currencies were not only weaker than the euro, they also had higher interest rates.

In an earlier chapter we discussed the problem created by the housing boom and eastern European mortgages denominated in euros, Swiss francs, and even yen. Banks in other EU countries owned many of the eastern European banks. Those banks in western Europe used euros and were under the financial oversight of the European Central Bank and the EU banking system. The eastern European countries were in the strange position of not owning their domestic banking systems. Rather than simply being supervised by their own governments, their banks were under foreign and EU supervision. A nation that doesn’t control its own financial system has gone a long way to losing its sovereignty. And this points to the future problem of the EU. The stronger members, like Germany, retained and enhanced their sovereignty during the financial crisis, while the weaker nations saw sovereignty decline. This imbalance will have to be addressed in the decade to come.