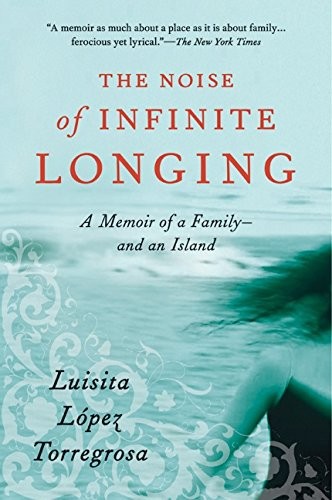

The Noise of Infinite Longing

Read The Noise of Infinite Longing Online

Authors: Luisita Lopez Torregrosa

-

HarperCollins e--books

The Noise of Inf inite Longing

The Noise of Infinite Longing

#

A Memoir of a Family— and an Island

Luisita López Torregrosa

This book is for my sisters, Angeles, Carmen, Sara, and Olga, and my brother, Amaury.

In memory of our mother.

“I am not certain as to how the pain of learning what is lost is transformed into light at last.”

—W. S. Merwin, “Testimony”

Contents

Epigraph

Prologue:

Texas, 1994, a Reunion

~

1

Part One

In the Beginning

One: An Island of Illusions

~

9

Two: Amor de Loca Juventud

~

35

Three: A City of Pyramids

~

55

Part Two

A Childhood in Pieces

Four: Playing in the Fields

~

71

Five: The Doctor’s Town

~

91

Six: Turning Points

~

119

Seven: In the Land of Snow

~

147

Eight: The Crackup

~

171

Part Three

A Scattering of Dreams

Nine: A Boy and His Drums

~

192

Ten: The Visionary

~

214

Eleven: A Raw Passion

~

Twelve: San Juan,

2001,

246

“This Sea, These Long Waves”

~

274

Acknowledgments

~

28

6

About the Author Credits

Cover Copyright

About the Publisher

Prologue

Texas,

1994,

a Reunion

T

he day my mother died, I was standing at the butcher-block counter of my kitchen, the sunlight harsh against the window- panes, and in my ear, on the telephone, my sister was shouting. She didn’t make it. She’s gone. I looked into the sun, blinded. Sara was sobbing into the phone. I heard my voice, deepening, slowing, as if my voice alone could rise against that flood and stop it. I wanted the details, the hour, the place, the last minutes. She was in the car, on the way to the post office, Sara said. Suddenly she grabbed her chest and said, It hurts, and then she was dead. None of it made sense to me. A car, a country road, mother on a stretcher, medics trying to revive her, the sirens. She was declared dead on arrival. But why did she die? I kept asking.We don’t know, Sara said. She spoke in bursts,

in little cries, incoherent.

I was standing inside the spread of sunlight that burned through the panes, leaning hard against the kitchen counter. My sister’s words seemed muffled, as if they were coming from an immense dis- tance, farther and farther, until I could barely hear her, her words becoming unintelligible. The room, the spot on the terra-cotta tiles where I stood holding the phone, became brighter, lighter. I could hear the birds in my garden, swooping down and out of the limbs of the old tree that leaned over the back fence.

They are all coming today, she said.

Tomorrow, I said, I’ll come tomorrow.

I hadn’t seen my mother in two years, the years when her hair had finally begun to gray and her voice had become thinner, tremu- lous. Her face, in her seventies, had become her own mother’s face, the cheeks sunken, her eyes deep sockets, still dark and opaque, stonewashed black. The crook of her nose was now more pro- nounced, like her mother’s, with her nostrils widened. But the skin of her face had almost no lines, without the indentations of her years. In the last pictures taken of her, at a candlelit dinner in New Orleans a month before her death, she was wearing her dangling emerald earrings, a short black sheath, and black sheer hose that showed off the calves she was so proud of. Her fine hair had been freshly trimmed, straight and feathery around her face. She looked ten years younger than her age.

Now she was gone, just like that. Later I would snap my fingers to remind myself, like a broken twig.

Angeles is already on her way, Sara was saying. She was coming from Tegucigalpa, flying over a thousand miles, believing that our mother was still alive. She would arrive in her snap-on sunglasses, smoking her unfiltered Honduran Camels, wearing those comfort- able sandals with the heels worn down. She was careless with her appearance, like women who were beautiful when they were very young.When we were teenagers I envied her looks, her femaleness, her cheekbones, her eyes so black, large, and unknowable—the ones keeping the secrets. She was a year younger than I, but from the time we were young girls she seemed fully shaped, nearly a complete woman. Now her beauty had aged, but it had deepened, the flavor fuller, thicker. She wore the marks of a life lived with abandon. She was Ava Gardner after Sinatra, after the high life.

My brother, Amaury, was flying in from NewYork, and he would arrive with his eyes bloodshot, heavy from crying. He had a mus-

tache, thick bristles that shadowed lips that were like my mother’s. His voice was loud, either mocking or angry like our father’s. He would arrive half drunk, his hands trembling, laughing and crying out of the same pain.

My younger sisters were coming, too. Olga, the youngest, who had in her blood the combustion of my parents’ temperament, was flying up from New Orleans with her husband and their two boys; and Car- men was driving in from West Texas, where her life was tennis and card games with the other ladies and raising perfect children, and the big house with the swimming pool. My aunt, Angela Luisa, was flying in from San Juan, coming all that way to see her only sister be buried in a countryside cemetery in a rural town in East Texas.

Over the phone I could hear the commotion in Sara’s house—in the background of her words, the slamming of refrigerator doors and the footfalls of people coming and going, people crying out, shouting. Her husband was calling out questions to her, making arrangements—did they have enough cars to take everyone back and forth from Dallas to my mother’s house some fifty miles away; who was going to sleep where; who was arriving when at the airport— the mundane logistics that come with a sudden death.

Then the phone connection was abruptly scrambled. Sara had to take another call, and she hung up in mid-sentence. And now there was only silence. I held on to the phone, still hearing my sister’s first words. She didn’t make it. She’s gone.

I was trembling head to foot, shaking uncontrollably, and at one in the afternoon, in the torpor of that Saturday in September, a time of year that was almost tropical in all that sunlight of late summer, I poured myself two fingers of gin, splashed the tonic, and squeezed the lime. I called the only person in the world who I thought could make sense of this for me, and she said, crying before I could, I’ll be right there. She came over and found me sitting tearless on a patio

chair in my garden. She picked up the hose and watered the droop- ing bamboo stalks and the withered azaleas, and we drank all after- noon.

T

hat night in my empty apartment, now emptier, I lay in my bed, dead myself. The walls seemed higher and whiter and empty of shadows. I left the bed and went to my living room and sat up all night, eyes grained, stinging, dry, as if I were waiting for some- body to come and tell me that it wasn’t true, that she was not dead,

not at all.

At five in the morning, when the sky was beginning to break free of night, I pulled the duffel bag off the top shelf of my closet. Slowly, counting the minutes and wanting to stop them at the same time, I took one shirt, then another, off their hangers and folded them carefully into the bag. I went through the mental list of travel, a list I knew from my years flying from one magazine assignment to another, and I was done in no time at all. I called up a taxi, and it showed up too soon, before I could make my rounds, locking doors, turning off lamps.

The taxi’s lights beamed on the still street.The driver opened the door for me, and I heard a click as it closed, loud in that silence of dawn. The airport terminal was already crowded. Lines formed at the ticket counters, bags pressed against me. People on holiday, peo- ple on urgent errands. I didn’t notice their faces.

At the counter, the clerk punched the computer keyboard, found my name. I blurted out, before I could stop myself, my mother is dead, I’m going to her funeral. The clerk’s face turned to me, eyes softening. She had heard this before, and her hand patted mine. I knew I would drink all the way to Dallas.

Sara was at the airport, waiting for me. I hadn’t seen her in four,

five years. She was taller than I remembered. Her light, long hair fell around a face that seemed gaunt to me, full of mourning, no, not yet, full of shock. Her eyes found me, and when I held her I could feel her bones, her long hands clasping my back. She was the next to the last of my parents’ six children, and when she was a child, when she was burned by scalding water and we believed she would die, even then she had a smile the rest of us didn’t have, a light about her that made her the only one of us who had what people call a good nature. In the car, driving to my mother’s house an hour away, she was valiantly trying to distract me, retelling the details, the funeral plans, the sleeping arrangements. She was the first among us to learn that mother was dead. She lived only an hour away and in those last years had become very close to mother. Telling me about mother’s last moments alive, details she had heard from mother’s husband, Sara’s voice, always high-pitched, was hitting higher notes, like a broken chord on a violin. Her light brown eyes had darkened with loss,

pitched dark like black screens.

We are going to mother’s house, she said.They are waiting for us.

I looked out the window at dry, flat land, the road straight and long. She talked all the way.

She is at the mortuary, she said.They embalmed her, her coffin is open, you may see her tonight.

No. I shook my head. I’m not looking at her. I don’t want to see her embalmed.

But she looks very good, Sara said. No, I said. She’s dead.

I blew smoke out the window.

Part One

In the Beginning

“The truth which I intend to set forth here is not particularly scandalous, or is so only to the degree that any truth creates a scandal.”

—MargueriteYourcenar,

Memoirs of Hadrian

Chapter One

An Island of Illusions

T

he box lay on my lap. I did not want to open it. Angeles sat across from me, in the torn leather chair in the room in Edge- wood, Texas, where my mother had kept her books, her photo albums, and the trinkets she had picked up in her travels. I had arrived just a few hours before and had walked around the house as if it were a church, slowly, gazing up at the pictures my mother had chosen to hang on the walls, looking at her bed, at her bottles of Arpège and her felt-lined jewelry box, staring unbelievingly at her

faded red robe still hanging on the back of the bathroom door.

My mother’s room had not been touched.The bed was made, the rose-colored bedspread smoothed around it, not a wrinkle in it, the way she had left it. Beside her bed, on her night table, she had a framed picture of my grandmother, a picture I had always loved, my grandmother in a gray and white housedress with dark stripes. Her face was powerful, nothing frail about it. It was the face of Spanish doñas, those Goya faces, smileless, almost ruthless, eyes long lost in some past. Next to the picture was a paperback edition of Toni Mor- rison’s

Beloved,

a book I had recommended to her. It lay there as if it had just been bought, no pages turned. Closest to the bed and my mother’s pillow was her latest crossword puzzle, which she had clipped from a newspaper. It was unfinished. I wanted to take it but didn’t dare touch it. I couldn’t touch any of it.