The novels, romances, and memoirs of Alphonse Daudet (2 page)

Read The novels, romances, and memoirs of Alphonse Daudet Online

Authors: 1840-1897 Alphonse Daudet

W. P. TRENT.

Pagb

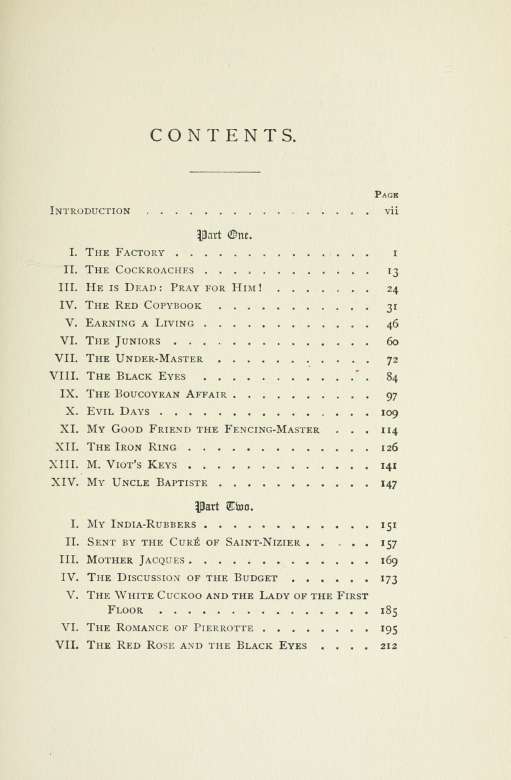

"VIII. A Reading at the Passage du Saumon . . . 225

IX. You Must Sell China 244

X. Irma Borel 259

XL The Sugar Heart 270

XII. Tolocototignan '. 285

XIII. The Escape 297

XIV. The Dream 310

XV. The Dream 323

XVI. The End of the Dream . 334

Prom Drawings by H. Laurent-Desrousseaux.

"' Little-What's-his-Name is going to drink some

toasts' " Frontispiece

'• In the Arbor" 128

" Irma Borel and ' Little-What s-his-Name ' " ... 287

PART I. CHAPTER I.

THE FACTORY.

I WAS born on the 13th of May, 18—, in a town of Languedoc, where, as in all Southern towns, there is a great deal of sunshine, not a little dust, a Cap melite convent, and a few Roman remains.

My father, M. Eyssette, who was at this time engaged in the silk industry, had, at the gates of the city, a large factory, in a part of which he had built himself a commodious dwelling-house shaded by plane-trees, and separated from the work-rooms by a large garden. It was there that I came into the world, and passed the first, the only happy years of my life. So it is that my grateful memory has kept an imperishable remembrance of the garden, the factory and the plane-trees; and when, after the ruin of my parents, it became necessary to leave these things, I really regretted them as if they had been human beings.

I must say, in the first place, that my birth brought no good luck to the Eyssette household.

Old Annou, our cook, has often told me since, how my father, then on a journey, received simultaneously the news of my appearance in this world, and that of the disappearance of one of his customers from Marseilles, who had gone off with more than forty thousand francs of his: so that M, Eyssette, pleased and pained at the same time, was naturally in doubt whether to weep over the disappearance of the customer from Marseilles, or to smile at the happy arrival of little Daniel. — You should have wept my dear M, Eyssette, you should have wept doubly.

It is true that I was my parents' unlucky star. From the very day of my birth, incredible misfortunes assailed them from all quarters. First, there was the customer from Marseilles, then two fires in one year, then the strike among the warpers, then our quarrel with my Uncle Baptiste, next a very costly lawsuit with our color-merchants, and, finally, the Revolution of i8—, which gave us the finishing stroke.

From this moment the factory was crippled; little by little the work-rooms became deserted; every week one more loom put by, every month one stamping-table the less. It was sad to see the life leaving our house, as if it were a sick body, slowly, a little day by day. At one time we stopped using the second story, and at another the back courtyard was given up. This lasted for two years; for two years the factory was dying. At last, one day, the workmen did not come; the factory bell did not ring, the wheel of the well

stopped squeaking, the water of the large pool in which the fabrics were washed remained motionless, and soon in the whole factory there were left only M. and Mme. Eyssette, old Annou, my brother Jacques and I; and away in the farther corner, the porter Colombe who remained to take care of the work-rooms, and his son little Rouget.

It was all over, we were ruined,

I was then six or seven years old. As I was very frail and sickly, my parents had not been willing to send me to school. My mother had taught me only how to read and write, and in addition, a few words of Spanish and two or three airs on the guitar, by the aid of which I had acquired in my family the reputation of a little prodigy. Thanks to this system of education, I never went away from home, and was a witness of the death of the house of Eyssette in all its details. I confess I was left unmoved by the spectacle; I found even that our ruin had its pleasant side, since I could frolic all over the factory at my own sweet will, and this I had been able to do only on Sunday when the workmen were there. I said gravely to little Rouget:

" Now the factory is mine; they have given it to me to play in." And little Rouget believed me. He believed in all I told him, little fool.

At home, however, everybody did not take our downfall so easily. All at once, M. Eyssette became very ill-tempered; his disposition was habitually irritable and fiery in the extreme; he loved shouting, violence and fury; but at the bottom he

was an excellent man, except that his hand was quick to strike, his voice loud, and that he felt an imperious need of making all those about him tremble. Ill fortune, instead of depressing him, incensed him. From morning till night, he was in a fearful rage, and, not knowing whom to attack, found fault with everything, with the sun, the mistral, Jacques, old Annou, and the Revolution, oh! above all, the Revolution! To hear my father, you would have sworn that this Revolution of i8— which had brought us to grief, was specially directed against us. So I beg you to believe that the Revolutionists were not in the odor of sanctity in the Eyssette household, God knows what we said of those gentlemen at that time. Even now, when old Papa Eyssette (whom God preserve to us) feels an attack of gout coming on, he stretches himself painfully on his sofa, and we hear him saying ! " Oh ! those Revolutionists ! "

At the time I am speaking of, M, Eyssette had no gout, and the sorrow of finding himself ruined had made him a terrible man whom nobody dared approach. He had to be bled once a week. Everybody about him was silent; we were afraid of him, and at table we asked for bread in a low voice. We did not dare even cry in his presence ; therefore, as soon as he had turned his back, there was but one sob from one end of the house to the other; my mother, old Annou, my brother Jacques, and my eldest brother, the Abbe, when he came to see us, all took part in it. My mother, of course, cried because she saw M. Eyssette unhappy; the Abb^

and old Annou cried because they saw Mme. Eyssette cry; as to Jacques, who was still too young to understand our misfortunes, — he was hardly two years older than I was, — he cried out of necessity, for the pleasure of it.

My brother Jacques was a strange child; he had the gift of tears. As far back as I remember, I can see him with red eyes and streaming cheeks. Morning, noon and night, at school, at home and out walking, he cried without ceasing, he cried everywhere. When anybody asked him : " What is the matter?" he answered sobbing: "Nothing is the matter; " and the most curious part of it is that there was nothing the matter. He cried just as people blow their nose, only oftener, that is all. Sometimes M. Eyssette was exasperated, and said to my mother: "That child is absurd; look at him! He is a river." Then Mme. Eyssette would answer in her sweet voice: " What can you expect, my dear? He will get over it as he grows up; at his age I was like him." In the meantime Jacques grew; he grew a great deal even, yet he did not get over it. On the contrary, the capacity this singular child had for shedding torrents of tears without any reason, increased daily, and so it was that the wretchedness of our parents was great good fortune to him. Once for all, he gave himself over to sobbing at his ease for whole days without anybody's asking him what the matter was.

In short, for Jacques as well as for me, our ruin had its pleasant side.

As to me, I was very happy. Nobody paid any more attention to me and I profited by this to play all day with Rouget in the empty work-rooms, where our steps echoed as if in a church, and in the great deserted courtyards, already overgrown with grass. Rouget, the son of Colombe the porter, was a big boy, about twelve years old, as strong as an ox, as devoted as a dog, as silly as a goose, and above all, remarkable for his red hair, to which he owed his nickname of Rouget. Only, I must tell you that Rouget for me was not Rouget: he was by turns my faithful Friday, a tribe of savages, a mutinous crew, or anything that was required of him. And at that time my name was not Daniel Eyssette; I was that extraordinary man, clad in the skins of beasts, whose adventures had been given to me, Master Crusoe himself. Sweet folly \ In the evening, after supper, I read over my Robinson Crusoe, I learned it by heart; in the daytime, I acted it, acted it madly, and enrolled in my comedy all the things that surrounded me. The factory was no longer the factory ; it was my desert island, oh, indeed a desert island! The pools served for the ocean, the garden was a virgin forest, and in the plane-trees there were quantities of crickets which were included in the play although they knew nothing of it.

Rouget, too, never suspected the importance of his r61e. If he had been asked who Robinson Crusoe was, he would have been much puzzled; still I must say that he discharged his duties with the fullest conviction, and that there was nobody

equal to him in imitating the roars of savages. Where had he learned this? I cannot tell, but it is nevertheless true that those great savage roars he brought out of the depths of his throat, as he shook his thick red hair, would have made the bravest tremble. Even I, Robinson himself, was sometimes frightened, and was obliged to say to him in a whisper: "Not so loud, Rouget; you make me afraid."

Unfortunately, if Rouget imitated the cries of savages very well, he knew still better how to repeat the coarse words of street children, and to take the Lord's name in vain. In playing with him, I learned to do as he did, and one day at table, somehow or other, a formidable oath escaped me. There was general consternation. " Who taught you that ? Where did you hear it ?" It was an event. M. Eyssette spoke immediately of putting me in a house of correction ; my eldest brother the Abbe said that first of all I should be sent to confession, since I had come to years of discretion. So they sent me to confession, and a great affair it was! I had to search through all the corners of my conscience to pick up a mass of old sins that had been lying about there for seven years. I could not sleep for two nights, there was such a heap of these devilish sins; I had put the smallest ones on top, but in spite of this the others could be seen; and when, kneeling in the little oaken wardrobe, I had to show them all to the Cur6 of the Recollets, I thought I should die of fear and confusion.

It was all over, I did not wish to play with Rou-get any longer; I knew now, for Saint Paul said it, and the Cure of the Recollets repeated it to me, that the devil is eternally wandering to and fro about us like a lion, qucsrens qiiem devoret. Oh, that qiiCBrens quem devoret, what an impression it made upon me ! I knew, too, that intriguing Lucifer takes all the shapes he wishes to tempt us; and you could not have cured me of the idea that he had hidden himself in Rouget to teach me how to take God's name in vain. So on returning to the factory, my first care was to inform Friday that he was to stay at home henceforward. Unfortunate Friday! This edict broke his heart; but he acquiesced without a murmur. Sometimes I saw him standing at the door of the porter's lodge, near the work-rooms; he was waiting sadly, and when he saw I was looking at him, the poor boy attempted to move my pity by roaring terribly, and shaking his flaming mane; but the more he roared, the farther away I kept from him. I thought he was like the famous lion qiicerens. I screamed to him: " Go away! I cannot endure you."

Rouget persisted in roaring thus for some days; then, one morning his father grew tired of hearing his roars at home, and sent him off to roar in an apprenticeship, and I saw him no more.

My enthusiasm for Robinson Crusoe did not cool for an instant. Just about this time my Uncle Baptiste suddenly became bored by his parrot and gave it to me. The parrot took the place

of Friday. I installed him in a pretty cage, in the inside of my winter dwelling; and there I was, more like Robinson Crusoe than ever, spending my days alone with this interesting bird, trying to make him say: "Robinson, poor Robinson!" But can you understand how it was that the parrot Uncle Baptiste had given me so as to be rid of its eternal chatter, persevered in not speaking as soon as he belonged to me? No more " Poor Robinson " than anything else; I could get nothing out of him. Nevertheless, I loved him very much, and took the greatest care of him.

We were living together, the parrot and I, in the most austere solitude, when one morning, a truly extraordinary thing happened to me. On that day, I had left my cabin early, and, armed to the teeth, was making explorations across my island. Suddenly I saw coming toward me a group of three or four persons who were speaking loud, and gesticulating with animation. Good Heavens ! Men in my island! I had only time to throw myself, down on my face, if you please, behind a cluster of oleanders. The men passed near me without seeing me; I thought I distinguished the voice of Colombe, the porter, and this reassured me a little; but, as soon as they were at a distance, I came out of my hiding-place and followed them afar off, to see what was going to come of all this.

The strangers stayed long in my island. They examined all its details from one end to the other. I saw them enter my grottoes, and sound the

lo Little What 's-His-Name.

depths of my oceans with their canes. From time to time they stopped and shook their heads. All my fear was, lest they should come and discover my dwellings. O God ! what would have become of me ! Luckily, this did not happen, and, at the end of half an hour, the men went away without even suspecting that the island was inhabited. As soon as they were gone, I rushed to shut myself up in one of my cabins, and spent the rest of the day in wondering who the men were and what they had come to do.

I was soon to know.

In the evening at supper M. Eyssette solemnly announced to us that the factory was sold, and that in a month we should leave for Lyons, where we were to live henceforward.

It was a terrible blow. It seemed to me that the sky was falling. The factory sold ! What! My island, my grottoes, my cabins !

Alas! M. Eyssette had sold the island, the grottoes, and the cabins; we had to leave everything. O God ! How I wept!

For a month, while at home they were packing the mirrors and the dishes, I walked, sad and lonely, about my dear factory. I had no heart to play, as you may imagine, oh, no! I sat down in all the corners, and looking at the objects about me, spoke to them as if they were people ; I said to the plane-trees : " Good-bye, my dear friends !" and to the pools: " It is all over, we shall never see each other any more." At the end of the garden there was a fine pomegranate-tree, with