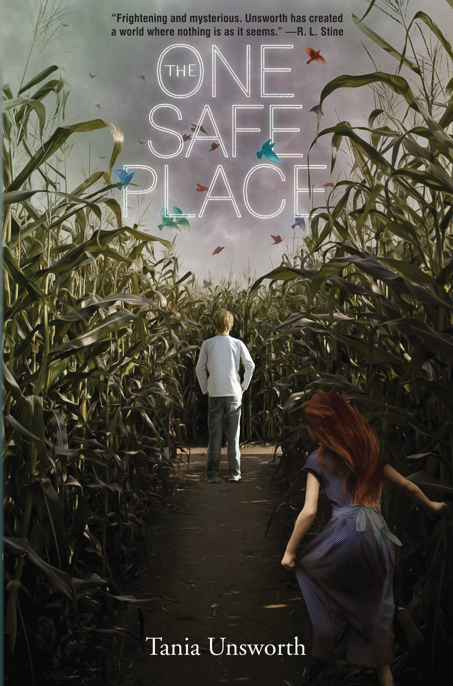

The One Safe Place

Read The One Safe Place Online

Authors: Tania Unsworth

The One Safe Place

Tania Unsworth

ALGONQUIN YOUNG READERS

2014

For Oscar, whom I love the most,

and Joe Ridley, my favorite

Contents

One

IT WAS THREE O’CLOCK

in the afternoon before Devin was done digging the grave. He had really finished it at two, but had carried on for an hour longer, partly to make sure it was good and deep and partly to delay what was coming next. He stood in the bottom of it, resting. The hole was higher than his waist; a rectangle with uneven sides. Devin would have liked to straighten it out. It was too broken up and prickly. But it was the best that he could do.

He threw the shovel over the side of the grave and hauled himself out. There was a slight breeze at the top of the hill, and he stood for a few moments looking out over the valley. In the land beyond, his grandfather had told him, there had once been corn. They used to farm it with machines as wide as houses and it poured like gold, rushing and endless, into vast granaries.

That was more than fifty years ago, before it got hot. It hardly ever rained now except for massive storms that darkened the skies for days. Huge areas of land had become useless, the dry soil swept away by the wind or by sudden, treacherous floods that ripped everything in their path. The change in the weather had started slow, but then it had come fast, faster than anyone expected. But it wasn’t just the weather that had changed, his grandfather said. It was people too. People had scattered. They lost homes and livelihoods, and desperation had turned their hearts as hard as the parched earth itself.

It was different on their small farm. The land was still good, a pocket of richness.

“We’re lucky, then,” Devin had said.

“We’re fortunate,” his grandfather corrected him.

It was important, his grandfather said, to keep to the right meanings of words or else they would be lost; blown away like the soil that had once grown enough corn to feed a nation. Other things also needed to be kept. Manners at table, the shine on the old silver vase. Every day, his grandfather fetched one of their books so Devin could practice his reading. They had five books. One was about farming, how to grow things and raise animals, and one was full of stories with no pictures except the ones the words made in your head. Another one had nothing but pictures, images of people who were dead now and places that were far away, and animals so strange they made Devin laugh.

“No,” his grandfather said when Devin stumbled over his reading. “That’s an

a

, not an

e

.”

“But they’re so hard to tell apart,” Devin complained. “Both so pale they fade into the page . . . and they won’t stop chirping, Granddad.”

“Chirping?”

“Like the swallows,” Devin explained.

When his grandfather smiled, his lips barely moved, as if his smile was another thing to be kept, guarded from view like a treasure. Instead you saw it mostly in his eyes. He reached out and touched Devin’s hand, and the taste on Devin’s tongue was half earthy, half sweet, like roots that had grown to fullness beneath the dark ground.

“Try again, Dev. Try again, my lad.”

Devin hadn’t thought his grandfather was old. He’d thought he was strong, as strong as the barn and the hills. He could labor all day until his shirt was wet through, but he’d never take it off and work naked to the waist because that was yet another thing to be kept: your standards. You had to keep your standards, he said, in such a shifting world. Since he’d been a boy, there’d been a thousand new inventions. You could do almost everything now just with the push of a button. But nothing had solved the problem of the heat, or the greed and hunger that had followed.

“Why not?” Devin had once asked.

His grandfather had squinted up into the blazing sun and pursed his lips.

“Nobody thought about the future, I guess. Too busy with other things.”

Devin couldn’t delay any longer. He picked up the shovel and turned back down the hill, toward the farmhouse. The basket of apples was still there where he’d dropped it, the fruit scattered all over the yard. His grandfather was still there too, lying on the porch with his eyes wide open and his long arms flung out. For half a second Devin thought he saw the fingers of one hand move and he scrambled up the stairs, falling to his knees as he grabbed for it.

But the hand was as cold as ice.

Tears of grief and panic rose in Devin’s eyes. But he couldn’t cry. There was nobody left to be strong except for him. He shoved his palms into his eyes, pressing back the tears.

“I dug it the best I could,” he told his grandfather. “It’s good and deep. The coyotes won’t find you. You’ll be safe.”

Devin stayed by his grandfather’s side for a long while. The shadows were growing long when he finally rose to his feet. He went into the bedroom and took the sheet off the bed and spread it wide and white on the porch. Then he half pushed, half rolled his grandfather onto it, his hands shaking and his breath coming fast. His horse, Glancer, named for her shy, sideways look, nickered softly from the orchard, and Devin hesitated. Then he covered his grandfather with the sheet and began to sew the sides together as quickly as he could.

When he was finished, he fetched Glancer, hitched her to the low wagon and brought her round to the front of the house. His grandfather’s heels banged on the porch stairs as Devin dragged him down, and each thud was like a blow to his heart. It took a long time to get the body into the wagon, but at last it was done and Devin slowly led Glancer up the hill, taking the shovel with him.

It was nearly dark and his grandfather was just a dim shape at the bottom of the grave, the sheet covering him as pale as the wing of a moth. After the struggle to move the body, Devin thought filling in the grave with earth would be easy. But it wasn’t. It felt like the hardest thing he had ever had to do. He stood holding the first shovelful of dirt, unable to move.

Burying his grandfather felt so final. And when it was done, he would be quite alone.

Although it was late, it was still hot. Devin put down the shovel and wiped the sweat from his face, catching the scent of rosemary on his fingers. It made a long, sighing sound, and a flash of blue, very bright and clean, shot for a second behind his eyes. The herb grew wild here on the top of the hill. Devin’s grandfather had pointed out the wiry plants, explaining that rosemary was the toughest of herbs, able to survive almost anywhere.

“Smells good, doesn’t it?” He’d held out a sprig for Devin to sniff. “A long time ago, people used to place it in graves for remembrance.”

Devin turned away now, searching in the gloom for the familiar plant. He found a bush and tugged a small branch free. For a second or two, he held it to his face, breathing in the scent, and then he tossed it into the grave and began shoveling in dirt as quickly as he could. “I’m sorry,” he told his grandfather. “I love you, I’m sorry.” He was crying now, his tears mingling with the dusty clods.

“I won’t forget you. I never will, no matter what.”

When the grave was all filled in, Devin collected rocks and placed them in a circle on top. Circles rang clear and they were always gold.

“Like the corn,” he told his grandfather. “Remember you told me you saw it? When you were a boy?”

It was a comfort knowing he could talk to his grandfather, even though he was dead. And if he closed his eyes, he could even imagine that his grandfather was talking right back to him.

But that night, alone in his bed, he couldn’t imagine his grandfather saying anything at all.

Devin woke before dawn and rose to do his chores. The chickens had to be fed and the wood collected and the cow watered and led out into the little field. He went as fast as he could, the bucket of water from the spring banging painfully against his shins as he stumbled across the yard.

The hay needed to be cut. It normally took him and his grandfather a full day and a half. Devin fetched his scythe and stood still for a moment, staring at the meadow. It suddenly seemed enormous. But he bent his head and set to work, not knowing what else to do, his arms moving automatically. By midday his hands were blistered and his breath was ragged with panic.

The grass was barely a quarter cut.

Leave a job undone, his grandfather always said, and it will just get bigger.

But Glancer’s stall needed to be cleaned out and the vegetable patch weeded, and the apples were still lying in the orchard . . . Devin worked all day and into the night, every hour a little further behind.

Midnight found him setting traps in the field for rabbits, his fingers trembling with fatigue. What if he actually caught one? What then? He had never killed a rabbit before. His grandfather always did it, his big hands quick and merciful. Devin had grown a lot in the last year, but there were still many things he couldn’t do.

His grandfather had gone before he could teach Devin everything. Perhaps like everyone else, his grandfather hadn’t thought enough about the future. He had been too busy with other things. Devin dropped his head and wept, too exhausted even to wipe his face.

The next day was worse than the one before, because his grandfather was right, jobs left undone just grew bigger and bigger. He ate the last of the cornbread and some raw carrots; there was nothing warm to eat because he hadn’t had time to fill the stove and light it. Despair began to creep over him.