The Origin of Humankind (11 page)

Read The Origin of Humankind Online

Authors: Richard Leakey

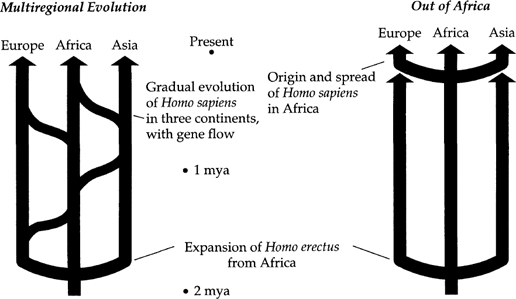

Instead of being the product of an evolutionary trend throughout the Old World, modern humans are seen in the alternative model as having arisen in a single geographical location (see

figure 5.2

). Bands of modern

Homo sapiens

would have migrated from this location and expanded into the rest of the Old World, replacing existing premodern populations. This model has had several labels, such as the “Noah’s Ark” hypothesis and the “Garden of Eden” hypothesis. Most recently, it has been called the “Out of Africa” hypothesis, because sub-Saharan Africa has been identified as the most likely place where the first modern humans evolved. Several anthropologists have contributed to this view, and Christopher Stringer, of the Natural History Museum, London, is its most vigorous proponent.

Two views of modern human origins. The multiregional model, left, states that

Homo erectus

populations expanded out of Africa close to 2 million years ago and became established throughout the Old World. Genetic continuity was maintained throughout the Old World by gene flow between local populations, so that the evolutionary trend toward modern

Homo sapiens

occurred in concert wherever populations of

Homo erectus

existed. The “Out of Africa” model, right, states that modern

Homo sapiens

evolved in Africa recently and quickly expanded into the rest of the Old World, replacing existing populations of

Homo erectus

and archaic

Homo sapiens

.

The two models could hardly be more different: the multiregional-evolution model describes an evolutionary trend throughout the Old World toward modern

Homo sapiens

, with little population migration and no population replacement, whereas the “Out of Africa” model calls for the evolution of

Homo sapiens

in one location only, followed by extensive population migration across the Old World, resulting in the replacement of existing premodern populations. Moreover, in the first model, modern geographical populations (what are known as “races”) would have deep genetic roots, having been essentially separate for as much as 2 million years; in the second model, these populations would have shallow genetic roots, all having derived from the single, recently evolved population in Africa.

The two models are also very different in their predictions of what we should see in the fossil record. According to the multiregional-evolution model, anatomical characteristics that we see in modern geographical populations should be visible in fossils in the same region, going back almost 2 million years, when

Homo erectus

first expanded its range beyond Africa. In the “Out of Africa” model, no such regional continuity over time is expected; indeed, modern populations should share African characteristics, if anything.

Milford Wolpoff, the strongest proponent of the multi-regional-evolution hypothesis, told an audience at the 1990 gathering of the American Association for the Advancement of Science that “the case for anatomical continuity is clearly demonstrated.” In northern Asia, for instance, certain features, such as the shape of the face, the configuration of the cheekbones, and the shovel shape of the incisor teeth, can be seen in fossils 750,000 years old; in the famous Peking Man fossils, which are a quarter of a million years old; and in modern Chinese populations. Stringer acknowledges this, but he notes that these features are not confined to northern Asia and therefore cannot be taken as evidence of regional continuity.

Wolpoff and his colleagues make a similar argument for Southeast Asia and Australia. But, as Stringer points out, the supposed sequence of continuity is built on fossils dated at only three time points: 1.8 million, 100,000, and 30,000 years ago. This paucity of reference points, says Stringer, weakens the case in the extreme.

These examples illustrate the problems anthropologists face. Not only are there differences of opinion over the significance of important anatomical features, but, Neanderthals aside, the fossil record is much slimmer than most anthropologists would like (and than most nonan-thropologists believe). Until these impediments are overcome, a consensus on the larger question may remain out of reach.

We can assess fossil anatomy from a different perspective, however. Neanderthals appear to have been stocky individuals with short limbs. This stature is an appropriate physical adaptation to the cold climatic conditions that prevailed throughout much of their range. The anatomy of the first modern humans in the same part of the world, however, is very different. These people were tall, slightly built, and long-limbed. A lithe body stature is much more suited to a tropical or temperate climate, not the frozen steppes of Ice Age Europe. This puzzle would be explicable if the first modern Europeans were descendants of migrants from Africa rather than having evolved in Europe, and the “Out of Africa” model therefore derives some support from this observation.

It receives further support from another direct observation of the fossil record. If the multiregional-evolution hypothesis is correct, then we would expect to find early examples of modern humans appearing more or less simultaneously throughout the Old World. That’s not what we see. The earliest-known modern human fossils probably come from southern Africa. I say “probably” because not only are these fossils fragmentary parts of jaws but there is a degree of uncertainty about their true age. For instance, the fossils from Border Cave and Klasies River Mouth Cave, both in South Africa, are thought to be a little more than 100,000 years old, and are adduced as support by proponents of the “Out of Africa” hypothesis. However, the modern human fossils from the caves of Qafzeh and Skhul are also close to 100,000 years old. It is possible, therefore, that modern humans first arose in northern Africa or the Middle East, and then migrated from there. Most anthropologists favor a sub-Saharan origin, however, based on the overall weight of the evidence (see

figure 5.3

).

No fossils of modern humans of this age have been found anywhere else in the rest of Asia or Europe. If this reflects evolutionary reality and is not simply the perennial problem of a lamentably incomplete fossil record, then the “Out of Africa” hypothesis does look reasonable.

The majority of population geneticists support this hypothesis as being the most biologically plausible. These scientists study the genetic profile within species, and how it might change through time. If populations of a species remain in geographical contact with each other, genetic changes that arise through mutation may spread throughout the entire region, by means of interbreeding. The genetic profile of the species will alter as a result, but overall the species will remain genetically unified. There is a different outcome if populations of a species have become geographically isolated from each other, perhaps because of a change in the course of a river or the opening of a desert. In this case, a genetic change that arises in one population will not be transferred to other populations. The isolated populations may therefore steadily become genetically different from one another, perhaps eventually becoming different subspecies, or even different species altogether. Population geneticists use mathematical models to calculate the rate at which genetic change may occur in populations of various sizes, and can therefore offer suggestions about what might have occurred in ancient times. Most population geneticists, including Luigi Luca Cavalli-Sforza, at Stanford, and Shahin Rouhani, of University College, London, who have commented extensively on the debate, are skeptical of the feasibility of the multiregional-evolution model. They note that the multiregional model requires extensive gene flow across large populations, linking them genetically while allowing evolutionary change to turn them into modern humans. And if new dates for Java Man fossils, announced early in 1994, are correct,

Homo erectus

expanded its range beyond Africa almost 2 million years ago. Therefore, not only would gene flow have to be maintained over a large geographical area, according to the multiregional-evolution model, it would also have to be maintained over a very long period of time. This, conclude most population geneticists, is simply unrealistic. With premodern populations spread across Europe, Asia, and Africa, there is a greater likelihood of producing geographical variants (such as we indeed see among archaic

sapiens)

than a cohesive whole.

A map of fossils. The map shows the location (and age in thousands of years) of fossils that relate to the origin of modern humans. The Neanderthals were restricted to the shaded area. The earliest specimens of modern humans have been found in sub-Saharan Africa and the Middle East.

We’ll leave fossils aside for a while, and turn to behavior, by which I mean its tangible products, tools and art objects. We have to remember that the vast preponderance of human behavior in technologically primitive human groups is archeologically invisible. For instance, an initiation ritual led by a shaman would involve the telling of myths, chanting, dancing, and body decoration—and none of these activities would enter the archeological record. Therefore we need to keep reminding ourselves, when we find stone tools and carved or painted objects, that they give us only the narrowest of windows onto the ancient world.

What we would like to identify in the archeological record is some kind of signal of the modern human mind at work. And we would like that signal to throw some light on the competing hypotheses. For example, if the signal appeared in all regions of the Old World more or less simultaneously, we could say that the multiregional-evolution model describes the most likely manner in which modern humans evolved. If, instead, the signal appeared first in an isolated location and then gradually spread to the rest of the world, this would give weight to the alternative model. We would hope, of course, that the archeological signal would coincide with the pattern from the fossil record.

We saw in

chapter 2

that the appearance of the genus

Homo

coincides roughly with the beginning of the archeological record, some 2.5 million years ago. We saw, too, that the increased complexity of stone-tool assemblages 1.4 million years ago, moving from the Oldowan industry to the Acheulean, followed soon upon the evolution of

Homo erectus

. The link between biology and behavior is therefore very close: simple tools were made by the earliest

Homo;

a jump in complexity occurred with the evolution of

Homo erectus

. That link is seen again with the appearance of archaic

sapiens

, some time after half a million years ago.

After more than a million years of relative stasis, the simple handaxe industry of

Homo erectus

gave way to a more complex technology fashioned on large flakes. And where the Acheulean industry had perhaps a dozen identifiable implements, the new technologies comprised as many as sixty. The biological novelty we see in the anatomy of the archaic

sapiens

, including the Neanderthals, is clearly accompanied by a new level of technological competence. Once the new technology had become established, however, it changed little. Stasis, not innovation, characterized the new era.

When change did come, however, it was dazzling—so dazzling that we should be aware that we might be blind to the reality behind it. About 35,000 years ago in Europe, people began making tools of the finest form, fashioned from delicately struck stone blades. For the first time, bone and antler were used as raw material for toolmaking. Tool kits now comprised more than one hundred items, and included implements for fashioning rough clothing and for engraving and sculpting. For the first time, tools became works of art: antler spear throwers, for example, were adorned with lifelike animal carvings. Beads and pendants appear in the fossil record, announcing the new practice of body decoration. And—most evocative of all—paintings on the walls of deep caves speak of a mental world we readily recognize as our own. Unlike previous eras, when stasis dominated, innovation is now the essence of culture, with change being measured in millennia rather than hundreds of millennia. Known as the Upper Paleolithic Revolution, this collective archeological signal is unmistakable evidence of the modern human mind at work.