The Oxford History of World Cinema (15 page)

Read The Oxford History of World Cinema Online

Authors: Geoffrey Nowell-Smith

the shot in which the words were uttered, but by about 1913 cutting in the title just as the

character spoke. This had the effect of forging a stronger connection between words and

actor, serving further to individuate the characters.

If the formal elements of American film developed in this period, its subject-matter also

underwent some changes. The studios continued to produce actualities, travelogues, and

other non-fiction films, but the story film's popularity continued to increase until it

constituted the major portion of the studios' output. In 1907 comedies comprised 70 per

cent of fiction films, perhaps because the comic chase provided such an easy means for

linking shots together. But the development of other means of establishing spatio-

temporal continuity facilitated the proliferation of different genres.

Exhibitors made a conscious effort to attract a wide audience by programming a mix of

subjects; comedies, Westerns, melodramas, actualities, and so forth. The studios planned

their output to meet this demand for diversity. For example, in 1911 Vitagraph released a

military film, a drama, a Western, a comedy, and a special feature, often a costume film,

each week. Nickelodeon audiences apparently loved Westerns (as did European viewers),

to such an extent that trade press writers began to complain of the plethora of Westerns

and predict the genre's imminent decline. Civil War films also proved popular, particularly

during the war's fiftieth anniversary, which fell in this period. By 1911 comedies no

longer constituted the majority of fiction films, but still maintained a significant presence.

Responding to a prejudice against 'vulgar' slapstick, studios began to turn out the first

situation comedies, featuring a continuing cast of characters in domestic settings;

Biograph's Mr and Mrs Jones series, Vitagraph's John Bunny series, and Pathé's Max

Linder series. In 1912 Mack Sennett revived the slapstick comedy when he devoted his

Keystone Studios to the genre. Not numerous, but none the less significant, were the

'quality' films: literary adaptations, biblical epics, and historical costume dramas.

Contemporary dramas (and melodramas), featuring a wide variety of characters and

settings, formed an important component of studio output, not only in terms of sheer

numbers but in terms of their deployment of the formal elements discussed above.

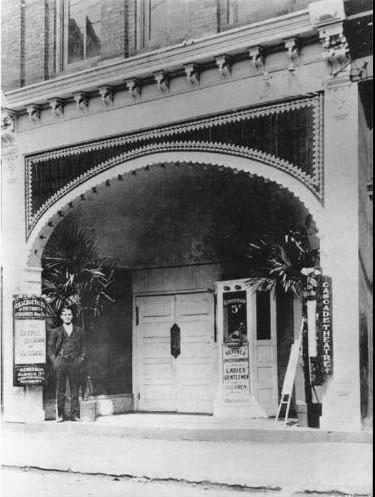

Warner's first cinema, 'The Cascade', in New Castle, Pennsylvania, 1903

These contemporary dramas display a more consistent construction of internally coherent

narratives and credible individualized characters through editing, acting, and intertitles

than do any of the other genres. In these films, producers often emulated the narrative

forms and characters of respectable contemporary entertainments, such as the 'realist'

drama (the proverbial 'well-made' play) and 'realist' literature, rather than, as in the earlier

period, drawing upon vaudeville and magic lanterns. This emulation resulted partially

from the film industry's desire to attract a broader audience while placating the cinema's

critics, thus entering the mainstream of American middle-class culture as a respectable

mass medium. Integral to this strategy were the quality films, which brought 'high' culture

to nickelodeon audiences just at the moment when the proliferation of permanent

exhibition venues and the 'nickel madness' caused cultural arbiters to fear the potential

deleterious effects of the new medium.

Although the peak period of quality film production coincided roughly with the first years

of the nickelodeon ( 1908-9), film-makers had already produced 'high-culture' subjects

such as

Parsifal

( Edison, 1904) and

L'ÉpopÉe napolÉonienne

( PathÉ, 1903-4). In 1908

the French

films d'art

provided a model that would be followed by both European and

American film producers as they sought to attain cultural legitimacy. The SociÉtÉ Film

d'Art was founded by the financial firm Frères Lafitte for the specific purpose of luring

the middle classes to the cinema with prestige productions; adaptations of stage plays or

original material written for the screen by established authors (often members of the

Académie Française), starring wellknown theatrical actors (often members of the

ComédieFrançaise), The first and most famous of the

films d'art, L'Assassinat du Duc de

Guise(The Assassination of the Duke of Guise),

derived from a script written by Académie

member Henri Lavedan. Although based on a historical incident from the reign of Henry

II, the original script constructed an internally coherent narrative intended to be

understood without previous extra-textual knowledge. Reviewed in the

New York Daily

Tribune

upon its Paris première, the film made a major impact in the United States.

Further articles on the

film d'art

movement appeared in the mainstream press, while the

film trade press asserted that the

films d'art

should serve to inspire American producers to

new heights. The exceptional coverage accorded

film d'art

may have served as an

incentive for American film-makers to emulate this strategy at a time when the industry

badly needed to assert its cultural bona fides.

The Motion Picture Patents Company encouraged the production of quality films, and one

of its members, Vitagraph, was particularly active in the production of literary, historical,

and biblical topics. Included in its list of output between 1908 and 1913 were. A Comedy

of Errors, The Reprieve: An Episode in the Life of Abraham Lincoln ( 1908); Judgment of

Solomon, Oliver Twist, Richelieu; or, The Conspiracy, The Life of Moses (five reels)

( 1909); Twelfth Night, The Martyrdom of Thomas à Becket ( 1910); A Tale of Two Cities

(three reels), Vanity Fair ( 1911); Cardinal Wolsey ( 1912); and The Pickwick Papers

( 1913). Biograph, on the other hand, concentrated its efforts on bringing formal practices

in line with those of the middle-class stage and novel, and its relatively few quality films

tended to be literary adaptations, such as After Many Years ( 1908) (based on Ten nyson 's

Enoch Arden) and The Taming of the Shrew ( 1908). The Edison Company, while not as

prolific as Vitagraph, did turn out its share of quality films, including Nero and the

Burning of Rome ( 1909) and Les Misérables (two reels, 1910), while Thanhouser led the

independents in their bid for respectability with titles such as Jane Eyre ( 1910) and

Romeo and Juliet (two reels, 1911).

EXHIBITION AND AUDIENCES

During the early years of film production, the dominance of the non-fiction film, and its

exhibition in 'respectable' venues -- vaudeville and opera-houses, churches and lecture

halls -- kept the new medium from posing a threat to the cultural status quo. But the

advent of the story film and the associated rise of the nickelodeons changed this situation,

and resulted in a sustained assault against the film industry by state officials and private

reform groups. The industry's critics asserted that the dark, dirty, and unsafe nickelodeons

showed unsuitable fare, were often located in tenement districts, and were patronized by

the most unstable elements of American society who were all too vulnerable to the

physical and moral hazards posed by the picture shows. There were demands that state

authorities censor films and regulate exhibition sites. The industry responded with several

strategies designed to placate its critics: the emulation of respectable literature and drama;

the production of literary, historical, and biblical films; self-censorship and co-operation

with government officials in making exhibition sites safe and sanitary.

Sir Herbert Beerbohm-Tree playing the title role in the first US version of Macbeth ( John Emerson, 1916). This was one in a series of

quality dramas, often adaptations of Shakespeare, that BeerbohmTree starred in following the success of the 1910 British film Henry

VIII

Permanent exhibition sites were established in the United States as early as 1905, and by

1907 there were an estimated 2,500 to 3,000 nickelodeons; by 1909, 8,000, and by 1910,

10,000. By the start of 1909, cinema attendance was estimated at 45 million per week.

New York rivalled Chicago for the greatest concentration of nickelodeons, estimates

ranging from 500 to 800. New York City's converted store-front venues, with their

inadequate seating, insufficient ventilation, dim lighting, and poorly marked, often

obstructed exits, posed serious hazards for their patrons, as confirmed by numerous police

and fire department memos from the period. Regular newspaper reports of fires, panics,

and collapsing balconies undoubtedly contributed to popular perceptions of the

nickelodeons as deathtraps. Catastrophic accidents aside, the physical conditions were

linked to ill effects which threatened the community in more insidious ways. In 1908 a

civic reform group reported: 'Often the sanitary conditions of the show-rooms are bad;

bad air, floors uncleaned, no provision of spittoons, and the people crowded closely

together, all make contagion likely.'

There is no accurate information on the make-up of cinema audiences at this time, but

impressionistic reports seem to agree that, in urban areas at least, they were

predominantly working class, many were immigrants, and sometimes a majority were

women and children. While the film industry asserted that it provided an inexpensive

distraction to those who had neither the time nor the money for other entertainments,

reformers feared that 'immoral' films -- dealing with crimes, adultery, suicide, and other

unacceptable topics-would unduly influence these most susceptible of viewers and, worse

yet, that the promiscuous mingling of races, ethnicities, genders, and ages would give rise

to sexual transgressions.

State officials and private reform groups devised a variety of strategies for containing the

threat posed by the rapidly growing new medium. The regulation of film content seemed

a fairly simple solution and in many localities reformers called for official municipal

censorship. As early as 1907, Chicago established a board of police censors that reviewed

all films shown within its jurisdiction and often demanded the excision of 'offensive'

material. San Francisco's censors enforced a code so strict that it barred 'all films where

one person was seen to strike another'. Some states, Pennsylvania being the first in 1911,

instituted state censorship boards.

State and local authorities also devised various ways of regulating the exhibition sites.

Laws prohibiting certain activities on the Christian Sabbath were invoked to shut the

nickelodeons on Sundays, often the wage-earners' sole day off and hence the best day at

the box-office. Authorities also struck at box-office profits through state and local statutes

forbidding the admission of unaccompanied children, depriving exhibitors of a major

source of income. Zoning laws were used to prohibit the operation of nickelodeons within

close proximity to schools or churches. In counter-attacking, the industry attempted to

form alliances with influential state officials, educators, and clergymen by offering

evidence (or at least making assertions) that the new medium provided information and

clean, amusing entertainment for those otherwise bereft of either education or diversion.