The Oxford History of World Cinema (60 page)

Read The Oxford History of World Cinema Online

Authors: Geoffrey Nowell-Smith

Lang's Metropolis was in its sixth month of production and would take another year to be

ready for release. Pommer went to Hollywood, where he produced two films for

Paramount with former Ufa star Pola Negri. But he had problems adapting to the

Hollywood system, and argued with the studio bosses.In 1928 Ufa's new studio head

Ludwig Klitzsch lured Pommer back to Babelsberg, where his production group was

given top priority to produce sound films. Combining his European and American

experience, he hired the Hollywood director Josef von Sternberg to direct Emil Jannings

in The Blue Angel (Der blaue Engel, 1930): an international film for the world market.

Pommer employed new talents such as the brothers Robert and Kurt Siodmak, and Billie

(later Billy) Wilder. He pioneered the genre of film operetta with films like Erik Charell's

The Congress Dances (Der Kongress tanzt, 1931).When the Nazis took power in 1933

and Ufa ousted most of its Jewish employees, Pommer emigrated to Paris, where he set

up a European production facility for Fox, for which he produced two films - Max

Ophuls's On a volé un homme ( 1933) and Fritz Lang's Liliom ( 1934). After a brief

period in Hollywood he moved to London to work with Korda. In 1937 he founded

Mayflower Pictures with actor Charles Laughton, whom he directed in Vessel of Wrath

( 1938). Hitchcock's Jamaica Inn ( 1939) was their last production before the Second

World War broke out and Pommer went to Hollywood for the third time. He produced

Dorothy Arzner's Dance, Girl, Dance for RKO but his studio contract was cancelled

following a heart attack.In 1946 Pommer (an American citizen since 1944) returned to

Germany as Film Production Control Officer. His tasks were to organize the re-

establishment of a German film industry and the rebuilding of destroyed studios, and to

supervise the denazification of film-makers. But Pommer found his position difficult,

caught between the interests of the American industry and his desire to reconstruct an

independent German cinema. In 1949 his duties on behalf of the Allies ended. He stayed

in Munich, working with old colleagues from Ufa such as Hans Albers, and new talents

such as Hildegard Knef. He produced a few films until the failure of the anti-war picture

Kinder, Mütter und ein General ( 1955) let to the collapse of his Intercontinental-Film. In

1956 Pommer, whose health was declining, retired to California, where he died in 1966.

HANS-MICHAEL BOCKBIBLIOGRAPHY

Bock, Hans-Michael, and Töteberg, Michael (eds.) 1992), das Ufa-Buch.

Hardt, Ursula ( 1993), Erich Pommer: Film Producer for Germany.

Jacobsen, Wolfgang ( 1989), Erich Pommer: Ein Produzent macht Filmgeschichte.

Friedrich Wilhelm Murnau (1888-1931)

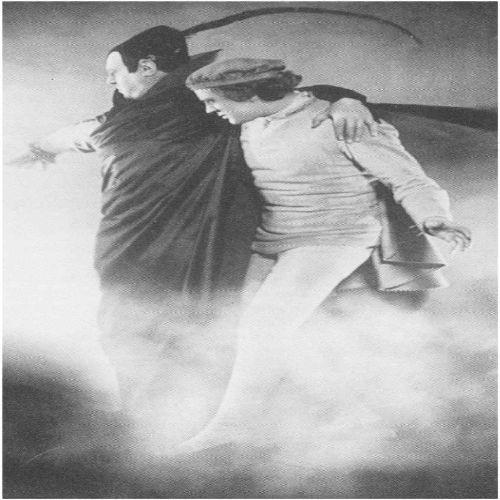

Faust ( 1926)

One of the most gifted visual artists of the silent cinema, F. W. Murnau made twenty-one

films between 1919 and 1931, first in Berlin, later in Hollywood, and finally in the South

Seas. He died prematurely in a car accident in California at the age of 42. Born Friedrich

Wilhelm Plumpe in Bielefeld, Germany, Murnau grew up in a cultured environment. As a

child, he immersed himself in literary classics and staged theatrical productions with his

sister and brothers. At the University of Heidelberg, where he studied art history and

literature, he was spotted by Max Reinhardt in a student play and offered free training at

Reinhardt's school in Berlin. When the war began in 1914, he enlisted in the infantry and

fought on the Eastern Front. In 1916 he transferred to the air force and was stationed near

Verdun, where he was one of the few from his company to survive.

In Nosferatu ( 1921), Murnau creates some of the most vivid images in German

expressionist cinema. Nosferatu's shadow ascending the stairs towards the woman who

awaits him evokes an entire era and genre of filmmaking. Based on Bram Stoker's

Dracula, Murnau's Nosferatu is a 'symphony of horror' in which the unnatural penetrates

the ordinary world, as when Nosferatu's ship glides into the harbour with its freight of

coffins, rats, sailors' corpses, and plague. The location shooting used so effectively by

Murnau was rarely seen in German films at this time. For Lotte Eisner ( 1969), Murnau

was the greatest of the expressionist directors because he was able to evoke horror outside

the studio. Special effects accompany Nosferatu, but because no effect is repeated exactly,

each instance delivers a unique charge of the uncanny. The sequence that turns to negative

after Nosferatu's coach carries Jonathan across the bridge toward the vampire's castle is

quoted by Cocteau in Orphé and Godard in Alphaville. Max Schreck as Nosferatu is a

passive predator, the very icon of cinematic Expressionism.

The Last Laugh (Der letzte Mann, 1924), starring Emil Jannings, is the story of an old

man who loses his job as doorman at a luxury hotel. Unable to face his demotion to a

menial position, the man steals a uniform and continues to dress with his usual ceremony

for his family and neighbours, who watch him come and go from their windows. When

his theft is discovered, his story would end in tragedy were it not for an epilogue in which

he is awakened, as if from a dream, to news that he has inherited a fortune from an

unknown man he has befriended. Despite the happy ending required by the studio, this

study of a man whose self-image has been taken away from him is the story of the

German middle class during the ruinous inflation of the mid-1920s. Critics around the

world marvelled at the 'unbound' (entfesselte), moving camera expressing his subjective

point of view. Murnau used only one intertitle in the film, aspiring to a universal visual

language.

For Eric Rohmer, Faust ( 1926) was Murnau's greatest artistic achievement because in it

all other elements were subordinated to mise-en-scène. In The Last Laugh and Tartüff

( 1925), architectural form (scenic design) took precedence, Faust was the most pictorial

(hence, cinematic) of Murnau's films because in it form (architecture) was subordinated to

light (the essence of cinema). The combat between light and darkness was its very

subject, as visualized in the spectacular 'Prologue in Heaven'. 'It is light that models form,

that sculpts it. The film-maker allows us to witness the birth of a world as true and

beautiful as painting, the art which has revealed the truth and beauty of the visible world

to us through the ages' ( Rohmer 1977 ). Murnau's homosexuality, which was not

acknowledged publicly, must have played a role in a aestheticizing and eroticzing the

body of the young Faust.

Based on the phenomenal success of The Last Laugh, Murnau was invited to Hollywood

by William Fox. He was given complete authority on Sunrise ( 1927), which he shot with

his technical team in his accustomed manner, with elaborate sets, complicated location

shooting, and experiments with visual effects. Sunrise: A Song of Two Humans is about

sin and redemption. A femme fatale from the city (dressed in black satin like the arch-

tempter Mephisto in Faust) comes to the country, where she seduces a man and nearly

succeeds in getting him to drown his wife before he recovers himself and tries to recreate

the simplicity and trust of their lost happiness. Sunrise overwhelmed critics with its sheer

beauty and poetry, but its costs far exceeded its earnings and it was to be the last film

Murnau made within a production system which allowed him real control. His subequent

films for Fox, Four devils and City Girl, were closely supervised by the studio. Murnau's

decisions could be overridden by others, and in his eyes both films were severely

damaged. None the less, City Girl should be appreciated on its own terms as a moral fable

in which the landscape (fields of wheat) is endowed with exquisite pastoral beauty that

turns dark and menacing, as in Nosferatu, Faust, and Tabu.In 1929 Murnau set sail with

Robert Flaherty for the South Seas to make a film about western traders who ruin a

simple island society. Wanting more dramatic structure than Flaherty, Murnau directed

Tabu ( 1931) alone. It begins in 'Paradise', where young men and women play in lush,

tropical pools of water. Reri and Matahi are in love. Nature and their community are in

harmony. Soon after, Reri is dedicated to the gods and declared tabu. Anyone who looks

at her with desire must be killed. Matahi escapes with her. 'Paradise Lost' chronicles the

inevitability of their ruin, represented by the Elder, who hunts them, and by the white

traders, who trap Matahi with debt, forcing him to transgress a second tabu in defying the

shark guarding the black pearl that can buy escape from the island. In the end, Matahi

wins against the shark but cannot reach the boat carrying Reri away. It moves across the

water as decisively as Nosferatu's ship, its sail resembling the shark's fin. Murnau died

before Tabu's premiére.JANET BERGSTROMFILMOGRAPHY Note: Starred titles are

no longer extant.* Der Knabe in Blau (Der Todessmarged) ( 1919); * Satanas ( 1919); *

Sehnsucht ( 1920); * Der Bucklige und die Tänzerin ( 1920); * Der Januskopf ( 1920); *

Abend-Nacht-Morgen ( 1920); Der Gang in die Nacht ( 1920); * Marizza, genannt die

Schmugglermadonna ( 1921); Schloss Vogelöd ( 1921); Nosferatu: Eine Symphonie des

Grauens ( 1921); Der brennende Acker ( 1922); Phantom ( 1922); * Die Austreibung

( 1923); Die Finanzen des Großherzogs ( 1923); Der letzte Mann (The Last Laugh)

( 1924); Herr Tartüff / Tartüff ( 1925); Faust ( 1926); Sunrise: A Song of Two Humans

( 1927); * Four Devils ( 1928); City Girl ( 1930); Tabu ( 1931)

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Eisner, Lotte ( 1969), The Haunted Screen.

-- ( 1973), Murnau.

Göttler, Fritz, et al. ( 1990), Friedrich Wilhelm Murnau.

Rohmer. Eric ( 1977), L'Organisation de l'espace dans le 'Faust' de Murnau.

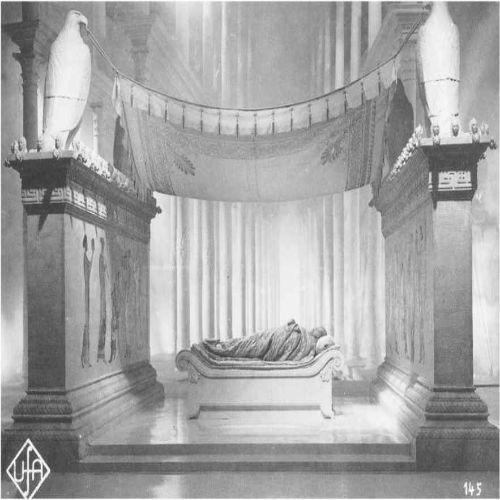

Robert Herlth (1893-1962)

Set design by Robert Herlth for the Ufa production Amphitryon ( 1935), directed by

Reinhold Schünzel

Robert Herlth, the son of a brewer, studied painting in Berlin before the First World War.

Drafted into the army in 1914, he was befriended by the painter and set designer Hermann

Warm, who helped his spend the last two years of the war at the army theatre in Wilna

and away from the front.

After the War, Warm became head of the art department at Erich Pommer's Decla-

Bioscop, and in 1920 he invited Herlth to join his team. Together with Walter Reimann

and Walter Röhrig, Warm had just created the 'expressionist' décors of Das Cabinett des

Dr Caligari ( 1919). When working on F. W. Murnau's Schloss Vogelöd ( 1921) and the

Chinese episode of Fritz Lang's Destiny ( Der müde Tod, 1921). Herlth was introduced to

Röhrig, and the two were to form a team lasting nearly fifteen years, mainly at the Decla-

Bioscop studios that were expanded by Ufa into the most important production centre in

Europe.

This was the time when, under the guidance of producer Erich Pommer, teams of set

designers and cinematographers laid the foundations on which the glory of Weimar

cinema was based.

The oppressive, dark, medieval interiors for Pabst's Der Schatz ( 1922-3) were among the

first collaborations of Herlth and Röhrig, who went on to design three films that form the

peak of German film-making in the 1920s; Murnau's The Last Laugh (Der letzte Mann,

1924), Tartüff ( 1925), and Faust ( 1926). They were involved with the productions from