The Oxford History of World Cinema (8 page)

Read The Oxford History of World Cinema Online

Authors: Geoffrey Nowell-Smith

bridge between the distinctive modes of early cinema and those which came later.

Broadly speaking, the early cinema is distinguished by the use of fairly direct

presentational modes, and draws heavily on existing conventions of photography and

theatre. It is only in the transitional period that specifically cinematic conventions really

start to develop, and the cinema acquires the means of creating its distinctive forms of

narrative illusion.

INDUSTRY

Various nations lay claim to the invention of moving pictures, but the cinema, like so

many other technological innovations, has no precise originating moment and owes its

birth to no particular country and no particular person. In fact, one can trace the origins of

cinema to such diverse sources as sixteenth-century Italian experiments with the camera

obscura, various early nineteenth-century optical toys, and a host of practices of visual

representation such as dioramas and panoramas. In the last decade of the nineteenth

century, efforts to project continuously moving images on to a screen intensified and

inventors/entrepreneurs in several countries presented the 'first' moving pictures to the

marvelling public: Edison in the United States; the Lumière brothers in France; Max

Skladanowsky in Germany; and William Friese-Greene in Great Britain. None of these

men can be called the primary originator of the film medium, however, since only a

favourable conjunction of technical circumstances made such an 'invention' possible at

this particular moment: improvements in photographic development; the invention of

celluloid, the first medium both durable and flexible enough to loop through a projector;

and the application of precision engineering and instruments to projector design.

In spite of the internationalization of both film style and technology, the United States and

a few European countries retained hegemony over film production, distribution, and

exhibition. Initially, French film producers were arguably the most important, if not in

terms of stylistic innovation, an area in which they competed with the British and the

Americans, then certainly in terms of market dominance at home and internationally.

Pride of place must be given to the Lumière brothers, who are frequently, although

perhaps inaccurately, credited with projecting the first moving pictures to a paying

audience. Auguste and Louis Lumière owned a photographic equipment factory and

experimented in their spare time with designing a camera that they dubbed the

Cinématographe. It was first demonstrated on 22 March 1895 at a meeting of the

Société

d'Encouragement à l'Industrie Nationale.

Subsequent to this prestigious début, the

Lumières continued to publicize their camera as a scientific instrument, exhibiting it at

photographic congresses and conferences of learned societies. In December 1895,

however, they executed their most famous and influential demonstration, projecting ten

films to a paying audience at the Grand Café in Paris.

Precisely dating the first exhibition of moving pictures depends upon whether 'exhibition'

means in private, publicly for a paying audience, seen in a Kinetoscope, or projected on a

screen. Given these parameters, one could date the first showing of motion pictures from

1893, when Edison first perfected the Kinetoscope, to December 1895 and the Lumières'

demonstration at the Grand Café.

The Lumières may not even have been the 'first' to project moving pictures on a screen to

a paying audience; this honour probably belongs to the German Max Skladanowsky, who

had done the same in Berlin two months before the Cinématographe's famed public

exhibition. But despite being 'scooped' by a competitor, the Lumières' business acumen

and marketing skill permitted them to become almost instantly known throughout Europe

and the United States and secured a place for them in film history. The Cinématographe's

technical specifications helped in both regards, initially giving it several advantages over

its competitors in terms of production and exhibition. Its relative lightness (16 lb.

compared to the several hundred of Edison's Kinetograph), its ability to function as a

camera, a projector, and a film developer, and its lack of dependence upon electric current

(it was hand-cranked and illuminated by limelight) all made it extremely portable and

adaptable. During the first six months of the Lumières' operations in the United States,

twenty-one cameramen/projectionists toured the country, exhibiting the Cinématographe

at vaudeville houses and fighting off the primary American competition, the Edison

Kinetograph.

The Lumières' Cinématographe, which showed primarily documentary material,

established French primacy, but their compatriot Georges Mélièlis became the world's

leading producer of fiction films during the early cinema period. Mélièlis began his career

as a conjurer, using magic lanterns as part of his act at the Théâtre RobertHoudin in Paris.

Upon seeing some of the Lumières' films, Mélièlis immediately recognized the potential

of the new medium, although he took it in a very different direction from his more

scientifically inclined countrymen. Mélièlis's Star Film Company began production in

1896, and by the spring of 1897 had its own studio outside Paris in Montreuil. Producing

hundreds of films between 1896 and 1912 and establishing distribution offices in London,

Barcelona, and Berlin by 1902 and in New York by 1903, Mélièlis nearly drove the

Lumières out of business. However, his popularity began to wane in 1908 as the films of

the transitional cinema began to offer a different kind of entertainment and by 1911

virtually the only Mélièlis films released were Westerns produced by Georges's brother

Gaston in a Texas studio. Eventually, competitors forced Mélièlis's company into

bankruptcy in 1913.

Chief among these competitors was the Pathé Company, which outlasted both Mélièlis

and the Lumières. It became one of the most important French film producers during the

early period, and was primarily responsible for the French dominance of the early cinema

market. PathéFrères was founded in 1896 by Charles Pathé, who followed an aggressive

policy of acquisition and expansion, acquiring the Lumières' patents as early as 1902, and

the Mélièlis Film Company before the First World War. Pathé also expanded his

operations abroad, exploiting markets. ignored by other distributors, and making his

firm's name practically synonymous with the cinema in many Third World countries. He

created subsidiary production companies in many European nations: Hispano Film

( Spain); Pathé-Russe ( Russia); Film d'Arte Italiano; and PathéBritannia. In 1908 Pathé

distributed twice as many films in the United States as all the indigenous manufacturers

combined. Despite this initial French dominance, however, various American studios,

primary among them the Edison Manufacturing Company, the American Mutoscope and

Biograph Company of America (after 1909 simply the Biograph Company), and the

Vitagraph Company of America (all founded in the late 1890s) had already created a solid

basis for their country's future domination of world cinema.

The 'invention' of the moving picture is often associated with the name of Thomas Alva

Edison, but, in accordance with contemporary industrial practices, Edison's moving

picture machines were actually produced by a team of technicians working at his

laboratories in West Orange, New Jersey, supervised by the Englishman William Kennedy

Laurie Dickson. Dickson and his associates began working on moving pictures in 1889

and by 1893 had built the Kinetograph, a workable but bulky camera, and the

Kinetoscope, a peep-show-like viewing machine in which a continuous strip of film

between 40 and 50 feet long ran between an electric lamp and a shutter. They also

developed and built the first motion picture studio, necessitated by the Kinetograph's size,

weight, and relative immobility. This was a shack whose resemblance to a police van

caused it to be popularly dubbed the 'Black Maria'. To this primitive studio came the

earliest American film actors, mainly vaudeville performers who travelled to West Orange

from nearby New York City to have their (moving) pictures taken. These pictures lasted

anywhere from fifteen seconds to one minute and simply reproduced the various

performers' stage acts with, for example, Little Egypt, the famous belly-dancer, dancing,

or Sandow the Strongman posing.

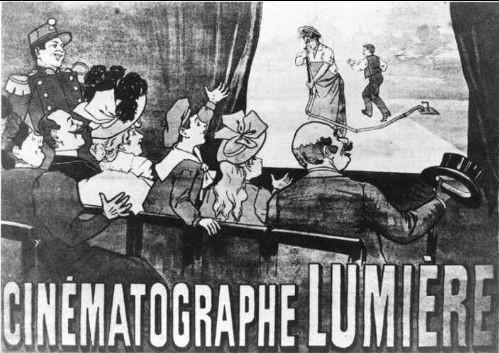

An early poster for the 'Cinématographe' with, on screen, the Lumière film Watering the Gardener (

L'Arroseur arrosé,

1895)

As with the Lumières, Edison's key position in film history stems more from marketing

skill than technical ingenuity. His company was the first to market a commercially viable

moving picture machine, albeit one designed for individual viewers rather than mass

audiences. Controlling the rights to the Kinetograph and Kinetoscope, Edison

immediately embarked upon plans for commercial exploitation, entering into business

agreements that led to the establishment of Kinetoscope parlours around the country. The

first Kinetoscope parlour, a rented store-front with room for ten of the viewing machines

each showing a different film, opened in New York City in April 1894. The new technical

marvel received a promotional boost when the popular boxing champion Gentleman Jim

Corbett went six rounds against Pete Courtney at the Black Maria. The resulting film

gained national publicity for Edison's machine, as well as drawing the rapt attention of

female viewers, who reportedly formed lines at the Kinetoscope parlours to sneak a peek

at the scantily clad Gentleman Jim. Soon other Kinetoscope parlours opened and the

machines also became a featured attraction at summer amusement parks.

Until the spring of 1896 the Edison Company devoted itself to shooting films for the

Kinetoscope, but, as the novelty of the Kinetoscope parlours wore off and sales of the

machines fell off, Thomas Edison began to rethink his commitment to individually

oriented exhibition. He acquired the patents to a projector whose key mechanism had

been designed by Thomas Armat and C. Francis Jenkins, who had lacked the capital for

the commercial exploitation of their invention. The Vitascope, which projected an image

on to a screen, was advertised under Edison's name and premièred in New York City in

April of 1896. Six films were shown, five produced by the Edison Company and one,

Rough Sea at Dover, by the Englishman R. W. Paul. These brief films, 40 feet in length

and lasting twenty seconds, were spliced end to end to form a loop, enabling each film to

be repeated up to half a dozen times. The sheer novelty of moving pictures, rather than

their content or a story, was the attraction for the first film audiences. Within a year there

were several hundred Vitascopes giving shows in various locations throughout the United

States.

In these early years Edison had two chief domestic rivals. In 1898 two former

vaudevillians, James Stuart Blackton and Albert Smith, founded the Vitagraph Company

of America initially to make films for exhibition in conjunction with their own vaudeville

acts. In that same year the outbreak of the Spanish-American War markedly increased the

popularity of the new moving pictures, which were able to bring the war home more

vividly than the penny press and the popular illustrated weeklies. Blackton and Smith

immediately took advantage of the situation, shooting films on their New York City

rooftop studio that purported to show events taking place in Cuba. So successful did this

venture prove that by 1900 the partners issued their first catalogue offering films for sale

to other exhibitors, thus establishing Vitagraph as one of the primary American film

producers. The third important American studio of the time, the American Mutoscope and

Biograph Company, now primarily known for employing D. W. Griffith between 1908

and 1913, was formed in 1895 to produce flipcards for Mutoscope machines. When W. K.

L. Dickson left Edison to join Biograph, the company used his expertise to patent a

projector to compete with the Vitascope. This projector apparently gave betterquality

projection with less flicker than other machines and quickly replaced the Lumières as