Authors: Hugh Ambrose

Tags: #United States, #World War; 1939-1945 - Campaigns - Pacific Area, #Pacific Area, #Military Personal Narratives, #World War; 1939-1945, #Military - World War II, #History - Military, #General, #Campaigns, #Marine Corps, #Marines - United States, #World War II, #World War II - East Asia, #United States., #Biography & Autobiography, #Military, #Military - United States, #Marines, #War, #Biography, #History

The Pacific (14 page)

The next day it was announced that they were headed for New Zealand, a journey that would take nineteen days because the convoy would have to zigzag as a precaution against submarines. The groans and grimaces accompanying the news came from most of the 2/1, who had decided after twenty- four hours that no place they had ever been rivaled

Elliott

for discomfort. Overcrowding made it difficult to sleep, eat, stand, or use the head. Discomfort gave way to disgust whenever the mess served chipped beef on toast, also known as shit on a shingle. When the ventilators went off in the holds, the marines blamed malicious swabbies. At the ship's store, the swabbies served the swabbies first, leaving their guests with few leftovers. Announcements over the ship's PA system blared commands frequently; each began with a loud "Now hear this . . ." The experience left the marines sputtering words like "rust bucket" and "African slaver."

Within a few days Sid found himself on a work detail, chipping the paint off the interior surfaces of the ship. As had been discovered during the attack on Pearl Harbor, the years of accumulated paint burned very well. The paint had to be removed for the safety of the ship. To Sid and the fifty others who had to do it, however, it felt like make-work and they cursed it heartily. One morning a massive sailor, the chief bosun's mate, came up to Sid as he was chipping paint and ordered him to follow.

"I am going to give you one of the best jobs available," the chief said, leading him to a large bathroom. Sid had just become the captain of the Officers' Head. "You are going to thank me in a few days." One deck below the ship's bridge, the head held six porcelain sinks, toilets, and urinals. Six shower stalls lined one wall. As he was instructed on how to keep all of the porcelain spotless, he thought of the long troughs of running seawater the men used for toilets downstairs. Here, he would be one of the few enlisted men with access to fresh water for bathing and washing his clothes. The tall bosun had been absolutely right.

Crossing the equator offered some relief from the days of washing the head and watching the flying fish. On July 1, the ship's crew observed the navy tradition of initiating the pollywogs into shellbacks, "into the solemn mysteries of the deep." The lieutenants of the 2/1 got the worst of it, getting their hair greased with oil by the order of Neptunus Rex, Ruler of the Raging Main. The ceremony lightened the mood on a ship on which men had been ordered not to toss their cigarette butts over the side, lest they leave a trail for an enemy submarine to follow. Crossing the equator also meant sitting out on deck in the warm night air, watching

Elliott

churn a long bright ribbon of phosphorescence behind it. A stargazer, Sid was excited to at last see the famed Southern Cross, only to be disappointed when he found it so "irregular." Sid and Deacon admitted, "We really are tired of salt water."

When land hove into view ten days later, though, the warmth of the equator had fallen far astern. July was winter in the Southern Hemisphere.

Elliott

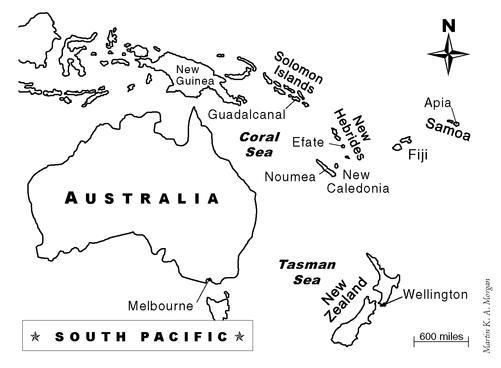

sailed into the harbor at Wellington, ringed with high mountains and busy with ships from all of the allied countries. As usual, a fair amount of waiting around preceded the moment when the enlisted men stepped off the ship into the cold and rain. Sid and Deacon went walking to take it all in--signs for Milk Bars, distinctive trams gliding by, cars with right-hand drives. Deacon observed that the city, although much larger than Mobile, looked "twenty years behind the times."

The New Zealanders welcomed the marines. At church one afternoon, Sid and Deacon met an older woman named Florence who invited them to her home for tea. Up the narrow streets they walked, wet and cold, carrying her groceries. Tall buildings had antiaircraft guns on them. All the windows were blacked out. Inside, they met Flo's invalid father and discovered her home did not have an icebox.

The escape from duty, however, ended quickly. All the privates of the 2/1 became members of working parties.

Elliott

was going to be combat- loaded immediately. In a ship loaded for combat, the equipment and supplies are organized to sustain men in combat efficiently. In other words, the equipment and supplies on the ship would now be unloaded so as to be reloaded. Although officially the word was that they were preparing for a three-month jungle training exercise, the speed and execution of the entire process made everyone aware that something big was going on. All the ships of the First Marines were unloading and loading. The Fifth Marine Regiment, which had arrived in Wellington before them, left their camps, came down to the docks, and began to load their ships. In the rain, night and day, at high speed, simultaneously, the process turned the docks into a chaotic mess.

For ten days, Sid worked four hours on and four hours off. He and the others hefted heavy boxes of ammunition from every weapon: 155mm, 105mm, 75mm, 90mm, 81mm, 37mm, 60mm, 20mm, .50 caliber, .30 cal, .45. The green boxes of .30-caliber ammunition had no handles, the mortar shells came in a peculiar cloverleaf packaging, and there were no gloves available to help with the spools of barbed wire. Cardboard boxes held all of their rations. The cardboard disintegrated in the rain, and soon the working parties stomped through a thick mush of wrappings and wasted food sprinkled with shiny tin cans.

With all of its hatches open, the ship could not be heated. The officers and NCOs observed the work; not one deigned to help. The Wellington dockworkers had gone on strike. Even some of the Yankees of How Company appeared adept at shirking. Sid cursed them all as a marine should, as his Rebel Squad of #4 gun put their backs into the job. Sailors manned the cranes and marines drove the trucks. When they loaded goodies like rations of chocolate, they stuffed some into their pockets. When they handled clothing, they stole some sweaters to keep warm and helped themselves to a clean pair of pants. A few other guys noticed and tried it, but got caught, much to the joy of Sid's squad.

Most days, Sid and the other members of #4 gun used their break to get off the dock and into the city. They bought lots of fruit, had a decent meal, or just got out of the weather by taking in a movie.

A Yank in the R.A.F.

was playing.

l

They met some New Zealand soldiers and compared weapons, emblems, and duties. The marines thought they learned a lot about the locals, including the use of "bloody" in most sentences, the preference for U.S. Marines over the U.S. Army, and the "heavenly ambition" of the young New Zealand women "to marry an American in the hopes of getting to the States." It surprised them to learn that the locals did not like to be called British, just as the people they met insisted on referring to Sid and Deacon as Yanks.

More ships arrived in the bay around them, including a dozen of the navy's big battleships and cruisers. When the work ended on July 20, #4 gun slipped off to have tea and meat pies at the Salvation Army. Afterwards, all of the 2/1 went on a conditioning hike in the hills. Hiking seemed like a relief after the drudgery of loading; at least it came with a view. That evening, Sid and Deacon, having heard they would be shipping out soon, bought two pounds of candy to take with them and were surprised at the glares of disgust they received from the locals. When the next morning brought no sergeants demanding work, everyone knew they were headed for "the real thing," which sounded like a destination. That evening

Elliott

got under way. The long convoy of troop transports, including the Fifth Marines and a number of battleships, sailed north. Announcements about "maneuvers" fooled few. Deacon spoke of the destiny before them being God's Will. Sid asked for his old job back, as captain of the Officers' Head. The silly title made him smile, but the rights and privileges improved life aboard the rust bucket.

THEIR LEAVES ENDED AFTER A WEEK AND THE PILOTS ALL REPORTED BACK TO Ford Island. Ensign Micheel noticed that most of the senior pilots, the old hands like his skipper, Gallaher, had disappeared. They had rotated home to train new squadrons and had, when they received their orders, departed before anyone changed their mind. Their haste seemed perfectly reasonable. Micheel and some of the other ensigns of Scouting Six were told to report to the commanding officer of Bombing Six at Naval Air Station Kaneohe. Mike's gunner, J. D. Dance, however, was not coming with him to the new squadron. The Aviation Radioman Third Class had requested flight training. Mike had happily written a recommendation, and Dance had been accepted.

The new members of Bombing Six found a warm welcome at NAS Kaneohe. A band played and cold beers were proffered to pilots and airmen as they stepped from their planes.

30

Located on the western edge of the island of Oahu, Kaneohe had only recently been constructed. The barracks, officers' club, and other buildings did not have air-conditioning, so the rooms grew pretty warm until the breeze came up in the late afternoon. A light rain usually followed. Unlike the airfields on the big island, Kaneohe sat well out of the flight traffic patterns, so there was little in the way of air traffic control. Life was easy.

Bombing Six had lost a lot of its veterans to reassignments. Lieutenant Ray Davis, the new skipper, had flown with a

Hornet

squadron at Midway. None of the dive-bombers off

Hornet

had sighted the enemy's carriers. Davis reviewed the files of his new men before interviewing them. In Ensign Micheel's personnel file, Scouting Six's skipper, Gallaher, had described him as "an enthusiastic and industrious young officer." For his service during the Battle of Midway, Lieutenant Gallaher had recommended that Ensign Vernon Micheel receive the Distinguished Flying Cross. Recommendations did not come stronger than that. When Lieutenant Davis asked Micheel in his interview to name his preferred duty, Mike said he wanted to continue to serve aboard a carrier in the Pacific. His voice was calm, his eyes steady. Ray saw something he liked in the blond- haired, blue-eyed ensign and designated him the squadron's flight officer. The administrative job, to be performed in addition to flight duties, did not mean as much to Mike as Ray's attitude. As Bombing Six began its regime of practice at NAS Kaneohe, Ensign Micheel discovered he was "one of the fellas."

SHIELDED FROM THE SUN AND ABLE TO GET ENOUGH CLEAN WATER, THE POWS in Bilibid Prison stopped suffering. They noticed their prison held men who had been incarcerated before the war as prominent Filipinos loyal to the United States. Bilibid also held anyone who was white, since the Japanese assumed Caucasians must be either American or British. One of the cells contained a German. He spoke English well enough to tell all of them of his devotion to the Nazi Party and Adolf Hitler. The Americans took to calling him Heine. For lack of something better to do, Shofner and his friends began to needle Heine, whose wonderful country had an alliance with the empire. "All you have to do is go see the Japanese commander and he would release you. After all, you are an ally of the Japs and you shouldn't be in here with us. You should be getting the royal treatment." Heine agreed and demanded to see the commandant, the prison warden, or whoever ran the prison. He came back bruised and beaten. He had no identification or proof, but that had not been the issue. The guards had not cared.

Heine could not understand why his country had allied with such an ignorant people. True Germans should have nothing to do with them. Shofner could not resist. "You saw the wrong man," he said. Heine demurred. But the prisoners had nothing but time in the jail and Captain Shofner was losing at poker, so he pressed on. "Heine, it's up to you to clear this matter up. You should go up and explain it again . . . the interpreter fouled it up some way . . ." Shifty and others amused themselves by egging him on. At last Heine's pride got the better of him and he went again. He returned bloodied once more, much to the amusement of all.

The guards came for the Filipinos first. A few days later, they selected a group of senior officers and took them away. Soon, the guards loaded a group of a few hundred men onto trucks every few days. Shofner, who was keeping a journal, knew that it was June 26 when he and about two hundred other prisoners bid Heine farewell. Many of the men were too weak to climb onto the trucks. They were driven to the Manila railroad station and loaded into steel railway boxcars. The guards crammed them in, approximately eighty men to each car, until there was not enough room for all the men to sit down. So the prisoners took turns standing and sitting. Those who sat had to sit between each other's legs. Six hours later, they arrived at a small station, where they boarded trucks. It turned out to be a short drive to Prisoner of War Camp Number One, Cabanatuan.

31