The Painter's Chair (5 page)

Read The Painter's Chair Online

Authors: Hugh Howard

IN SMIBERT’S TIME, the preparation of

materia pictoria

could be as time-consuming as the act of painting itself.

The canvases were made of woven flax. John Smibert, Merchant, ordered these linen “cloaths” (he also rendered the word “Cloats”)

from his lifelong friend, Arthur Pond, a sometime painter, etcher, and art dealer. Pond shipped them to America from London,

where back-street artisans produced the canvases in quantity. Smibert ordered the larger ones to be “rolled up & put in a

case” (so as to take up less shipping space), whereas the smaller ones arrived already “strained” (stretched).

Like his London peers, John Smibert, Painter, worked on canvases that had already been sized. In preparing a canvas, a London

colourman would have warmed (but not boiled) granules of hide glue (typically rabbit-or pigskin) to a thick liquid the consistency

of honey. The sizing was then spread on a canvas in broad strokes using a palette knife. Once the glue dried, the surface

was sanded smooth with a pumice stone.

The grounding came next. Its composition varied, with common ingredients including plaster, the sediment from a jar of brush-cleaning

oil, or carbon black, as well as the essential linseed oil and white-lead pigment. Smibert preferred a grayish-green or reddish

ground, but whatever the ingredients, the application of the grounding produced a smooth surface, less absorbent than raw

linen but still able to retain some of the fabric’s tooth and flexibility.

As a purveyor of colors, Smibert sold few ready-to-use paints; his trade was in the ingredients used to make them. These included

such vehicles as oils, dryers, turpentine, shellacs and other varnishes, and the all-important pigments.

Most of the pigments Smibert sold were made from earths and minerals that had been processed (usually by firing or cooking),

dried on long boards or stones, and then

levigated

, meaning they were finely ground into powders by a hand mill or with a mortar and pestle. For larger quantities, the tool

of choice was a muller, a stone with one flat side that was held in the palm and worked in circles on a stone slab. Depending

upon their source, iron-rich soils called ochers produced pigments ranging in color from pale yellow to orange and red. Thus

terra di Sienna

, when burned (calcined), produced an orange-red hue called burnt Sienna; a scarlet red was termed Venetian red; the brown-red

was Spanish brown. The mineral copper was used to produce greens (“Distilled Verdigres,” specified one bill of lading from

London). Mercury ore (quicksilver) made cinnabar, a bright red vermilion pigment. Other colors that Smibert ordered from Pond

in London included “French Sap Green” (made from buckthorn berries), “English Saffron” (a tincture of the spice saffron),

and “Prussn. Blew . . . of a fine deep sort.”

9

Prussian blue was the first chemical color of the age, made not from an earth or other natural pigment but from a salt compound

of iron and potassium. The carmine that Smibert ordered (“very fine,” he specified), was highly prized, having actually traveled

across the ocean twice, coming as it did from Mexico or South America via London (it was derived from the eggs and body of

the cochineal insect). The primary white pigment was flake white, made of white lead, favored because it was durable and tough

yet flexible.

Pigments became paints when the fine powders were mixed with oil or another material to help bind the pigment to the canvas.

When small quantities were required, the mixing was done on the palette itself with a thin-bladed palette knife. Larger quantities

could be mixed on a stone or muller. The blended oil and pigment looked uniform, though the tiny grains of pigment were merely

suspended in the liquid, like currants in cake batter. After the paint was applied, it would thicken from a paste to a solid

in a chemical reaction as the oil set (oxidized). A tough film remained, dry to the touch in a matter of hours. Most paints

on the palette needed to be mixed each day, as one day’s batch would dry by the next day.

The painting process itself required several sittings and a gradual buildup of layers of paint in a prescribed order. Sometimes

the painter began with a chalk or graphite sketch, but when the time came to begin a painting, Smibert worked in so-called

dead colors. For this under-painting, he would rough out his first vision of the painting, indicating in dull tones the largest

areas of form and color, perhaps the gentleman’s coat or background drapery. He applied the paint with a “fitch,” a rough,

square-ended brush often made from the hair of the skunklike polecat (or “fitchew”). Once he established the relationship

of the biggest elements, Smibert could refine his pictorial idea, since the neutral tones of the paint enabled him to correct

what he did not like, to exchange darks for lights, to rethink what he had done. By the time he completed the underpainting,

the monochromatic canvas before him was usually a fair representation of the composition as it would appear in the finished

painting.

When he moved on to more detailed work, he employed a good-quality pointed brush called a “street pencil.” Using paints thinned

with turpentine, he could render the hair and other details. He began working with brighter colors and used glazes (tinted

and transparent oily mixes) and thin washes for backgrounds and detail. The tendency was to paint the sitter’s clothing and

surroundings more freely. A thicker, paste-like paint was used for flesh tones. Layers of paint, varying from thin and translucent

to thick and opaque, were built up for visual effect, adding shading or enhancing and deepening the colors beneath. After

the painting was finished, a varnish (a gum resin dissolved in spirits) was usually applied both to protect the painted surface

and to give the finished product a sheen that intensified the contrasting colors. A minimum of several days was required to

allow the layers of paint, glaze, and varnish to dry.

As he neared the end of his life, the infirm and nearly blind Smibert continued to sell casks of paint, pails, jars, and a

wide variety of other supplies. Among the wares he imported from London, in addition to canvases and pigments, were papers,

silver and gold leaf, and the makings for “Fanns” (the painting of fans was a popular ladies’ pastime). For all the goods

that he sold, however, it was his knowledge of painting, as well as the paintings he had made, that proved of inestimable

value. Even in death, Smibert would continue to influence the artistic climate of his adopted city.

III.

1751–1795 . . . Smibert’s Painting Room . . . Queen Street

T

HE LEGACY SMIBERT left to his wife included “The easterly half of the House and Land in Queen Street,” which was valued at

446 pounds, 13 shillings, 4 pence. As prepared in February 1752, his probate inventory also listed a fourteen-acre farm on

the city’s outskirts (£186.13.4), silver plate (£36.6.4), linens (£34.4.5), feather Beds and Bedsteads (£29.6.8), as well

as Chests, five Looking Glasses, a slave named Phillis, and other goods. He had become a man of considerable means.

After the house, the second most valuable item was the inventory of Smibert’s shop, principally the “Colours & Oyls,” with

an estimated value of 307 pounds, 16 shillings, and 5 pence. Further down the list appeared entries for objects that, despite

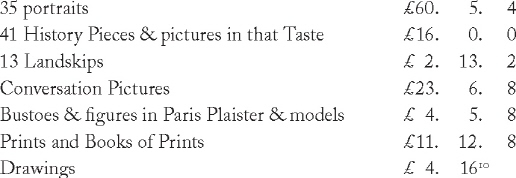

lesser monetary worth, would prove of surprising importance. They included the following:

Some of these were the same works of art with which Smibert had begun Boston’s aesthetic education back in 1730. He had also

held a sale in 1734 at which, on Monday, March 27, he offered for purchase “A Collection of Valuable PRINTS [and] . . . a

Collection of Pictures in Oil Colours.”

11

Some prints and frames had been sold but the majority of his collection remained in his studio, and it had become a regular

stop for visitors to Boston. One out-of-towner who came to look at the “fine pictures” was Dr. Alexander Hamilton, a fellow

Scotsman then residing in Annapolis. He was so taken by what he saw during his summer call in 1744 that he visited Mr. Smibert’s

again a few days later. After the second survey he recorded in his

Itinerarium

, “I . . . entertained myself an hour or two with his paintings.”

12

After Smibert’s will had been filed and probated, surprisingly little changed. His widow, Mary, and a nephew, John Moffatt,

continued to operate the color shop. One flight up, the dead painter’s art collection remained unsold and available for study.

The Painting Room, its walls lined with green baize, provided a suitable backdrop for the works themselves, which amounted

to something of a summary of the painter’s life. It was a mingling of Smibert portraits and landscapes, together with the

Old Master copies dating from his Italian sojourn. It would prove to be another of Mr. Smibert’s firsts, as this well-lit

room was soon to become a place of pilgrimage. Smibert’s Painting Room was, in effect, America’s only art museum in the days

before the Revolution.

P

ETER PELHAM, ANOTHER aging English émigré, also died in Boston in 1751. Though he and Mary Copley had been married barely

three years, in that time Pelham had introduced her son, John, to a world the boy had not previously known.

John Singleton Copley had spent his first ten years living over the family tobacco shop on Long Wharf before moving to his

stepfather’s home on Lindal’s Row near the upper end of King Street. Though less than a half a mile away, Boston’s commercial

center seemed very different from the maritime bustle of the old neighborhood, with its transient population of sailors and

the ceaseless coming-and-going of ships. On King Street, the nearby Town House was a commanding presence, the center of government

in Boston. John Smibert resided in this new neighborhood, too, which was dominated by merchants, shop keepers, and craftsmen.

Mary Copley advertised her wares in the

Boston Gazette

, proclaiming hers “the best

Virginia

Tobacco, Cut, Pigtail and spun, of all Sorts, by Wholesale or Retail, at the cheapest Rates.”

13

To supplement his income, her new husband drew upon his English education, offering his colonial neighbors the chance to improve

themselves. Peter Pelham taught reading, writing, and arithmetic and gave instruction in etiquette, needlework, and dancing.

The adolescent John Singleton Copley absorbed everything he could from Pelham, a former Londoner who had arrived in Boston

with the urban savvy of a man who had spent his first thirty-two years negotiating the teeming streets of Eu rope’s largest

city.

Among the lessons the boy learned from his stepfather was the wizardry of the mezzotint. As the first to engrave a mezzotint

in the colonies, Pelham had great skill with the essential tool of his trade, the

burin

, which was used to scrape a pitted copper plate to allow areas, rather than just lines, to be inked. The technique produced

prints with subtle tones that conveyed the illusion of human skin and delicate fabrics, making the medium well suited to portraiture.

Although he was a competent painter in oils upon his arrival in America in 1727, Pelham set aside his brushes after John Smibert

brought his superior skills to Boston. The two men had become collaborators, and Pelham’s prints of ministers and other worthies

of the day, many of them copied from Smibert’s original oils, helped establish a local market for prints.

Not long after Pelham’s death, his young stepson—Copley was going on sixteen—tried his hand at the mezzotint. After the death

of a prominent Boston minister in 1753, Copley chose a plate his stepfather had made ten years before after a Smibert portrait.

Using the burnisher, he obliterated part of the Smibert–Pelham likeness of another minister, leaving the clerical collar,

coat, and cape in place. He substituted a new head, reworking the copper so that it bore the bewigged visage of the just-deceased

reverend. Pleased with his work, the young artisan also changed the inscription, replacing the names of the original painter

and engraver with

“J.S. Copley pinx

t

et fecit.”