The Paris Architect: A Novel

Read The Paris Architect: A Novel Online

Authors: Charles Belfoure

Copyright © 2013 by Charles Belfoure

Cover and internal design © 2013 by Sourcebooks, Inc.

Cover design by Catherine Casalino

Cover photography © Jitka Saniova/Arcangel Images, riekephotos/Shutterstock, Ala Alkhouskaya/Shutterstock, Alchena/Shutterstock

Sourcebooks and the colophon are registered trademarks of Sourcebooks, Inc.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form or by any electronic or mechanical means including information storage and retrieval systems—except in the case of brief quotations embodied in critical articles or reviews—without permission in writing from its publisher, Sourcebooks, Inc.

The characters and events portrayed in this book are fictitious or are used fictitiously. Any similarity to real persons, living or dead, is purely coincidental and not intended by the author.

Published by Sourcebooks Landmark, an imprint of Sourcebooks, Inc.

P.O. Box 4410, Naperville, Illinois 60567-4410

(630) 961-3900

Fax: (630) 961-2168

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Belfoure, Charles

The Paris architect : a novel / Charles Belfoure.

pages cm

Includes bibliographical references and index.

(hardcover : alk. paper) 1. Architects—France—Paris—Fiction. 2. World War, 1939–1945—Underground movements—France—Paris—Fiction. 3. Jews—France—History—Fiction. 4. France—History—German occupation, 1940–1945—Fiction. 5. Paris (France)—History—1940–1944—Fiction. 6. Historical fiction. I. Title.

PS3602.E446P37 2013

813’.6—dc23

2013017034

Contents

1

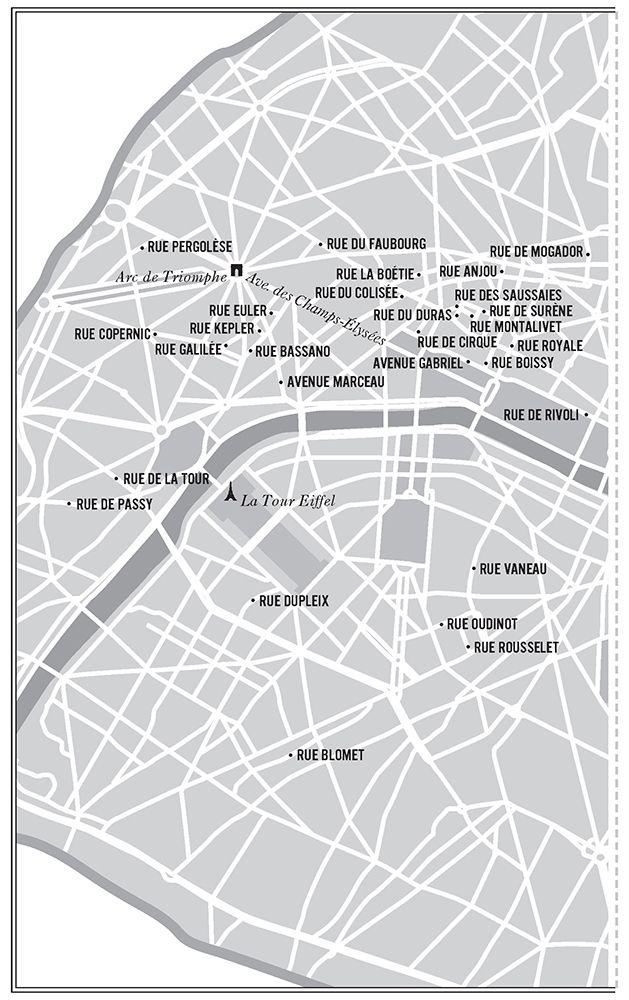

Just as Lucien Bernard rounded the corner at the rue la Boétie, a man running from the opposite direction almost collided with him. He came so close that Lucien could smell his cologne as he raced by.

In the very second that Lucien realized he and the man wore the same scent, L’Eau d’Aunay, he heard a loud crack. He turned around. Just two meters away, the man lay face down on the sidewalk, blood streaming from the back of his bald head as though someone had turned on a faucet inside his skull. The dark crimson fluid flowed quickly in a narrow rivulet down his neck, over his crisp white collar, and then onto his well-tailored navy blue suit, changing its color to a rich deep purple.

There had been plenty of killings in Paris in the two years since the beginning of the German occupation in 1940, but Lucien had never actually seen a dead body until this moment. He was oddly mesmerized, not by the dead body, but by the new color the blood had produced on his suit. In an art class at school, he had to paint boring color wheel exercises. Here before him was bizarre proof that blue and red indeed made purple.

“Stay where you are!”

A German officer holding a steel-blue Luger ran up alongside him, followed by two tall soldiers with submachine guns, which they immediately trained on Lucien.

“Don’t move, you bastard, or you’ll be sleeping next to your friend,” said the officer.

Lucien couldn’t have moved if he’d wanted to; he was frozen with fear.

The officer walked over to the body, then turned and strolled up to Lucien as if he were going to ask him for a light. About thirty years old, the man had a fine aquiline nose and very dark, un-Aryan brown eyes, which now stared deeply into Lucien’s gray-blue ones. Lucien was unnerved. Shortly after the Germans took over, several pamphlets had been written by Frenchmen on how to deal with the occupiers. Maintain dignity and distance, do not talk to them, and above all, avoid eye contact. In the animal world, direct eye contact was a challenge and a form of aggression. But Lucien couldn’t avoid breaking this rule with the German’s eyes just ten centimeters from his.

“He’s not my friend,” Lucien said in a quiet voice.

The German’s face broke out into a wide grin.

“This kike is nobody’s friend anymore,” said the officer, whose uniform indicated he was a major in the Waffen-SS. The two soldiers laughed.

Though Lucien was so scared that he thought he had pissed himself, he knew he had to act quickly or he could be lying dead on the ground next. Lucien managed a shallow breath to brace himself and to think. One of the oddest aspects of the Occupation was how incredibly pleasant and polite the Germans were when dealing with their defeated French subjects. They even gave up their seats on the Metro to the elderly.

Lucien tried the same tack.

“Is that your bullet lodged in the gentleman’s skull?” he asked.

“Yes, it is. Just one shot,” the major said. “But it’s really not all that impressive. Jews aren’t very athletic. They run so damn slow it’s never much of a challenge.”

The major began to go through the man’s pockets, pulling out papers and a handsome alligator wallet, which he placed in the side pocket of his green and black tunic. He grinned up at Lucien.

“But thank you so much for admiring my marksmanship.”

A wave of relief swept over Lucien—this wasn’t his day to die.

“You’re most welcome, Major.”

The officer stood. “You may be on your way, but I suggest you visit a men’s room first,” he said in a solicitous voice. He gestured with his gray gloved hand at the right shoulder of Lucien’s gray suit.

“I’m afraid I splattered you. This filth is all over the back of your suit, which I greatly admire, by the way. Who is your tailor?”

Craning his neck to the right, Lucien could see specks of red on his shoulder. The officer produced a pen and a small brown notebook.

“Monsieur. Your tailor?”

“Millet. On the rue de Mogador.” Lucien had always heard that Germans were meticulous record keepers.

The German carefully wrote this down and pocketed his notebook in his trouser pocket.

“Thank you so much. No one in the world can surpass the artistry of French tailors, not even the British. You know, the French have us beat in all the arts, I’m afraid. Even we Germans concede that Gallic culture is vastly superior to Teutonic—in everything except fighting wars, that is.” The German laughed at his observation, as did the two soldiers.

Lucien followed suit and also laughed heartily.

After the laughter subsided, the major gave Lucien a curt salute. “I won’t keep you any longer, monsieur.”

Lucien nodded and walked away. When safely out of earshot, he muttered “German shit” under his breath and continued on at an almost leisurely pace. Running through the streets of Paris had become a death wish—as the poor devil lying facedown in the street had found out. Seeing a man murdered had frightened him, he realized, but he really wasn’t upset that the man was dead. All that mattered was that

he

wasn’t dead. It bothered him that he had so little compassion for his fellow man.

But no wonder—he’d been brought up in a family where compassion didn’t exist.

His father, a university-trained geologist of some distinction, had had the same dog-eat-dog view of life as the most ignorant peasant. When it came to the misfortune of others, his philosophy had been tough shit, better him than me. The late Professor Jean-Baptiste Bernard hadn’t seemed to realize that human beings, including his wife and children, had feelings. His love and affection had been heaped upon inanimate objects—the rocks and minerals of France and her colonies—and he demanded that his two sons love them as well. Before most children could read, Lucien and his older brother, Mathieu, had been taught the names of every sedimentary, igneous, and metamorphic rock in every one of France’s nine geological provinces.

His father tested them at suppertime, setting rocks on the table for them to name. He was merciless if they made even one mistake, like the time Lucien couldn’t identify bertrandite, a member of the silicate family, and his father had ordered him to put the rock in his mouth so he would never forget it. To this day, he remembered bertrandite’s bitter taste.