THE PARTLY CLOUDY PATRIOT (9 page)

Read THE PARTLY CLOUDY PATRIOT Online

Authors: Sarah Vowell

So how could Gore have become more likable and yet remained true to his wonky self? By taking a few cues from the Willow character on

Buffy.

Willow is not a self-hating nerd. She is a self-deprecating nerd. While Gore, like Giles, is the butt of other people’s dork jokes, Willow, a postmodern nerd, peppers her cerebral monologues with one-liners that make light of her own book learning. For instance, substitute-teaching a computer science class she said, “For next time read the chapter on information grouping and binary coding. I bet you’ll think coding is pretty cool. If you find two-digit multi-stacked conversions and primary number clusters a big hoot.” See what she did there? She neither hid her knowledge nor annoyed anyone. She made knowing arcane specifics seem funny and fun.

When I was talking to Doug the

Buffy

writer about how Gore had missed out on the usefulness of the postmodern nerd’s self-deprecating impulse, I couldn’t put my finger on what to call it. But at the end of the conversation, I mentioned that I had just finished watching all the

Revenge of the Nerds

movies on videotape. (If you want to up the nerd ante, watch those films and take notes.)

Revenge of the Nerds II

is the one where the nerd fraternity attends a frat convention in Florida and all the jock frats want to get rid of the nerds. The jocks dress up as Seminole Indians to try to scare the nerds away. One of the nerds, Poindexter, shouts some gibberish at the “Indians,” but nothing happens. He turns to his nerd friend and says, “I don’t think those guys are Indians. When I said ‘bite my crank’ in Seminole, no one responded.”

I told Doug, “I was sitting there taking notes and actually yelled at my television, ‘Hey, there’s no such language as Seminole! The Seminole speak two dialects—Creek and Miccosukee!’”

Doug reflects on this admission for a moment, then asks, “Did you notice that when you told me that story, you did a voice? See? You even did it to yourself. You used the nerd voice!”

The nerd voice. That’s what it should be called, that self-deprecating impulse that Gore lacks. Doug’s right. I apologized for being a nerd, even when talking privately to another nerd. It was organic, unconscious, I didn’t know I was doing it. According to Doug, that’s how he and the other

Buffy

writers fashion Willow’s nerd voice dialogue. He says there’s not “a lot of conscious thought behind it, like, ‘Let’s put in a disclaimer here.’ I think that’s just the way we talk. I think everyone on the staff is a recovering nerd. When you declare your genuine passion for something, you are so setting yourself up. You just automatically take the shot before anyone else does. It’s this preemptive mockery.”

While the preemptive mockery software is automatically included in most nerd brains under the age of forty, it still needs to be installed in Gore. Self-deprecation is not standard baby boomer operating procedure—they were the most aggressive self-aggrandizing generation of the twentieth century and aren’t particularly good at making fun of themselves.

Any politician tricky enough to get elected to the House, not to mention the vice presidency, must necessarily have the kind of postmodern mind which thinks simultaneously about both what he is saying and the way he is saying it. As a national Democrat, Gore has had to frame his arguments about, say, energy policy, remembering that his support base includes both the United Auto Workers and members of the Sierra Club. So he already has the cerebral capability required to give a proper name-heavy speech about the China conundrum followed by an icebreaking wisecrack about not going to the prom. It’s silly, demeaning, and time-consuming, for sure, but for a nerd, what part of driving a tank or pulling on cowboy boots is not?

Any person who wants any job, who knows he would be good at the job, knows he has to fake his way through the dumb job interview before he’s actually allowed to roll up his sleeves. I asked Doug what he thought would have happened in the campaign if, instead of donning khakis and cowboy boots and French-kissing his wife on TV, Gore had been truer to himself and said what he thought and knew and believed using the nerd voice. Doug didn’t hesitate: “Oh my God, he’d be president for life.”

I wish it were different. I wish that we privileged knowledge in politicians, that the ones who know things didn’t have to hide it behind brown pants, and that the know-not-enoughs were laughed all the way to the Maine border on their first New Hampshire meet and greet. I wish that in order to secure his party’s nomination, a presidential candidate would be required to point at the sky and name all the stars; have the periodic table of the elements memorized; rattle off the kings and queens of Spain; define the significance of the Gatling gun; joke around in Latin; interpret the symbolism in seventeenth-century Dutch painting; explain photosynthesis to a six-year-old; recite Emily Dickinson; bake a perfect popover; build a shortwave radio out of a coconut; and know all the words to Hoagy Carmichael’s “Two Sleepy People,” Johnny Cash’s “Five Feet High and Rising,” and “You Got the Silver” by the Rolling Stones. After all, the United States is the greatest country on earth dealing with the most complicated problems in the history of the world—poverty, pollution, justice, Jerusalem. What we need is a president who is at least twelve kinds of nerd, a nerd messiah to come along every four years, acquire the Secret Service code name Poindexter, install a

Revenge of the Nerds

screen saver on the Oval Office computer, and one by one decrypt our woes.

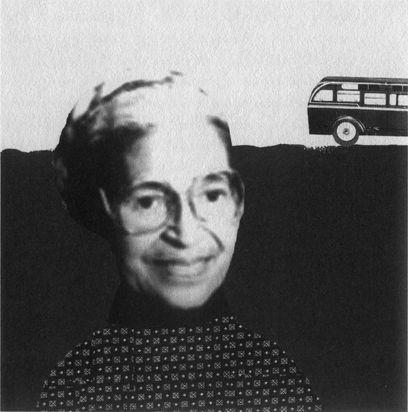

Rosa Parks,

C’est Moi

A

ccording to Reuters, on January 20, 2001 in Washington, the special guest at the Florida state inaugural ball was introduced by the country singer Larry Gatlin. He said, “In France it was Joan of Arc; in the Crimea it was Florence Nightingale; in the Deep South there was Rosa Parks; in India there was Mother Teresa, and in Florida there was Katherine Harris.”

I leave it to my Indian, Crimean, and French colleagues to determine how the Florida secretary of state is or is not similar to Teresa, Florence, or St. Joan. As for Rosa Parks, Katherine Harris can get in line. Because people around here can’t stop comparing themselves to Parks. To wit:

The mayor of Friendship Heights, Maryland, has proposed an outdoor smoking ban because, according to

The Washington Post

, citizens “with asthma or other illnesses ‘cannot have full access’ to areas where smokers are doing their evil deed. The mayor compares this horrific possibility to Rosa Parks being sent to the back of the bus.”

A California dairy farmer protesting the government’s milk pricing system poured milk down a drain in front of TV cameras, claiming that he had to take a stand, “just like Rosa Parks had to take a stand.”

A street performer in St. Augustine, Florida, is challenging a city ordinance that bans him from doing his act on the town’s historic St. George Street. The performer’s lawyer told

The Florida Times-Union

, “Telling these people they can exercise their First Amendment rights somewhere other than on St. George is like telling Rosa Parks that she has to sit in the back of the bus.” (Which is, coincidentally, also the argument of another Florida lawyer, this one representing adult dancers contesting Tampa’s ordinance outlawing lap dancing.) I would also like to mention the rocker, marksman, and conservative activist Ted Nugent, who in his autobiography,

God, Guns and Rock ’n’ Roll

, refers to himself as “Rosa Parks with a loud guitar.” That’s so inaccurate. Everyone knows he’s more like Mary Matalin with a fancy deer rifle.

Call me picky, but breathing secondhand smoke, being subject to unfair dairy pricing, and not being able to mime (or lap dance), though they are all tragic, tragic injustices, are not quite as bad as the systematic segregation of

public

transportation based on skin color. And while fighting for your right to lap dance and mime and breathe just the regular pollution is a very fine, very American idea, it is not quite as brave as being a middle-aged black woman in Alabama in 1955 telling a white man she’s not giving him her seat despite the fact that the law requires her to do so. And, oh, by the way, in the process, she gets arrested, and then sparks the Montgomery bus boycott, which is the seed of the civil rights movement as we know it. The bus boycotters not only introduced a twenty-six-year-old pastor by the name of Martin Luther King, Jr., into national public life but, after many months of car pools, walking, and court fights against bus segregation, got the separate but equal doctrine declared illegal once and for all.

It’s not just people on the right like Katherine Harris and Ted Nugent who seem especially silly being likened to Parks. I first cringed at this analogy trend at the lefty Ralph Nader’s October 2000 campaign rally in Madison Square Garden. Ever sit in a coliseum full of people who think they’re heroes? I was surrounded by thousands of well-meaning, well-fed white kids who loved it when the filmmaker Michael Moore told them they should, like Rosa Parks, stand up to power, by which I think he meant vote for Nader so he could qualify for federal matching funds. When Nader himself mentioned abolitionists in Mississippi in 1836 and asked the crowd to “think how lonely it must have been,” he was answered, according to my notes, with a “huge, weird cheer.” I think I’m a fine enough person—why, the very next morning I was having people over for waffles. But I hope I’m not being falsely modest by pointing out that I’m no Harriet Tubman. And I’m certainly no Rosa Parks. As far as I’m concerned, about the only person in recent memory who has an unimpeachable right to compare himself to Parks is that Chinese student who stared down those tanks in Tiananmen Square.

I was reminded of those Naderites watching a rerun of the sitcom

Sports Night

on Comedy Central. Dan, a television sportscaster played by Josh Charles, has been ordered by his network to make an on-air apology to viewers because he said in a magazine interview that he supports the legalization of marijuana. He stands by his opinion and balks at apologizing. His boss, Isaac (Robert Guillaume), agrees but tells him to do it anyway “because it’s television and this is how it’s done.” Dan replies, “Yeah, well, sitting in the back of the bus was how it was done until a forty-two-year-old lady moved up front.” A few minutes later Isaac looks Dan in the eye and tells him, “Because I love you I can say this. No rich young white guy has ever gotten anywhere with me comparing himself to Rosa Parks.” Finally, the voice of reason, which of course was heard on a canceled network TV series on cable.

Analogies give order to the world—and solidarity. Pointing out how one person is like another is reassuring, less lonely. Maybe those who would compare their personal inconveniences to the epic struggles of history are just looking for company, and who wouldn’t want to be in the company of Rosa Parks? On the other hand, perhaps people who compare themselves to Rosa Parks are simply arrogant, pampered nincompoops with delusions of grandeur who couldn’t tell the difference between a paper cut and a decapitation.

In defense of Ted Nugent, the street performer, the mayor, the dairy farmer, the lap dancers, the Naderites, and a fictional sportscaster, I will point out that Katherine Harris is the only person on my list of people lamely compared to a civil rights icon who, at the very moment she was being compared to a civil rights icon, was actually being sued for “massive voter disenfranchisement of people of color during the presidential election”—by the NAACP.

Tom Cruise Makes Me Nervous

D

uring the three-plus hours I sat in the dark watching Paul Thomas Anderson’s ensemble epic

Magnolia

, I found myself wanting something I’d never wanted before. More Tom Cruise. As a white, middle-class American moviegoer who graduated from high school during the Reagan administration and subscribes to more than one cable film channel, I’ve seen every film Tom Cruise ever made, some many more than once, without even trying. Like a Tom Petty or a Jim Lehrer, Cruise falls into that category of competent if ubiquitous public figures that have never won my love or hate and therefore never truly caught my eye. Except for his memorably baroque turn as Lestat in

Interview with the Vampire

, which I, like the rest of the country, blame on his curdled blond hair. But somehow, Cruise’s work in

Magnolia

, as the male prowess guru Frank T. J. Mackey, so seized my curiosity that I walked straight out of the theater to go rent his 1983 film

Risky Business.

Tom Cruise is a mystery in plain sight. If one sets out to explain his appeal, all the normal movie star reasons melt away. For starters, his looks. Cruise has never been a breathtaking beauty. The shock of

Risky Business

, especially if your head’s full of the flawless teens currently steaming up the television, is how ordinary Cruise looks. He’s a regular, awkward kid, to the extent that I doubt he’d be cast in the lead now. Cruise’s face is too angular to be sensual. Whoever said that there are no straight lines in nature never bought a ticket to

The Firm.

His face reminds me more of a math problem than a love poem, the nose and chin right out of high school geometry, hard vectors of flesh. Picasso might have liked to paint him, though it would have been too easy—turning breasts and lips into rectangles is more of a challenge than making a box like Cruise boxier. Even his hair is drawn on with a ruler. Check out his short and sporty coif in

Mission: Impossible;

every individual strand is a line parallel to the y-axis. Which might explain a little of the

Magnolia

draw. Cruise’s longer locks in that picture do make his face look a little softer, or as soft as it’s possible for a man to look while swaggering around a stage inciting other men to date rape proclaiming, “Respect the cock!”

I’d never given Tom Cruise’s cock much thought before. If I had been asked to draw a nude Tom Cruise before seeing the bulge protruding out of his white underwear as he strips in

Magnolia

, I probably would have given him the smooth anatomy of a Ken doll. Where Tom Cruise sticks his privates has been the subject of rumors and lawsuits, but I never gave Cruise’s sexuality much truck one way or the other. Because, watching his movies over the past couple of weeks, I am constantly surprised when Cruise is in the same room with another person, much less the same bed. He strikes me as utterly, quintessentially, fundamentally alone. Of course Stanley Kubrick wanted Cruise to play the doctor in his

Eyes Wide Shut.

Much of the movie requires the doctor to walk the streets of New York by himself at night, and when a director needs alone-in-a-crowd, he calls Tom Cruise. The running gag about his title character in

Jerry Maguire

was that Jerry hates to be alone, but he also can’t connect with anyone. In that sense,

Jerry Maguire

is the perfect fable of America’s relationship with Tom Cruise. Basically, we think he’s a stuck-up phony and we want to see him hit bottom, have his love interest notice for once that he isn’t paying any attention to her, and then we want to see him humanized, i.e., cry. Cruise’s first two Oscar nominations—for

Jerry Maguire

and

Born on the Fourth of July—

display the public’s deep desire to see him put through a ringer. We want him to get his legs cut off

(July)

, and we want to see him lose for a while to the even slicker, if that’s possible, Jay Mohr

(Maguire)

because we want to punish him. Because I think the only reason seemingly every man, woman, and child in America goes to see his movies is not that he blinds us with beauty or talent or emotion. We can’t take our eyes off him because he makes us a little nervous. Not too nervous—that’s why we invented Dennis Hopper. Cruise makes us stealth nervous, just jittery enough to keep us awake.

Watch Barry Levinson’s

Rain Man

again and I guarantee you that the discomfort of Dustin Hoffman’s shticky autism does not compare to the heebie-jeebies of Cruise’s performance. Hoffman can dodder on about missing

Jeopardy!

every thirteen seconds and he’s fresh air, but Cruise, closed off and angry, is a twitch fest. When Huffman’s Raymond throws a fit as Cruise tries to give him a hug, the viewer more than understands. While autism is the most natural thing in the world, an embrace from Cruise defies the laws of nature. When the cute little kid in

Jerry Maguire

gave Cruise a hug, my first reaction was parental. I wanted to grab the child away, scolding, “We don’t do that. We don’t touch burning stoves, strangers’ candy, and we do not touch Tom Cruise.” Because Cruise is not, as the French say, good in his skin. Even in his most flawless, most affable performance, as Lt. Daniel Kaffee in

A Few Good Men

, Cruise seems the most comfortable on the softball field, having conversations with Demi Moore through a fence. Because Tom Cruise is the most talented actor of all time at keeping his distance.

Like most screen icons, Tom Cruise is not of us. Us, with our faces lumped together out of concentric circles versus his straight-edge mug. Us with our nerves and fears and him with his lieutenant-lawyer cockiness. Him with his choreographed cocktails and us dripping gin on our carpets as olives splash on the floor. But that’s where Tom Cruise stops—better than. There’s no further inspiration to be gained. Like every time I see

To Kill a Mockingbird

I take one look at Gregory Peck’s Atticus Finch and resolve to become more dignified. Even seeing Rene Russo in the remake of

The Thomas Crown Affair

made me vow to dress better, which, if not a moral for our times, is at least some little something. Cruise’s best line in

Magnolia

comes when his character is asked by the reporter interviewing him why he’s stopped talking. “I’m quietly judging you,” he seethes, and that might be just what we’re afraid of with regards to Tom Cruise.

The mark of a great performance is that it obliterates distance, gets under our skin. It’s simply harder for an icon to do that. But possible.

Magnolia

is the first time Cruise even comes close. It is far and away his most physical performance. If only because I’d never heard him breathe. About half of Cruise’s on-screen time is taken up with Mackey’s rooster struts—again, alone—across a darkened stage. His entrance, a ridiculous backlit pose to the strains of “Also Sprach Zarathustra,” isn’t his only Elvis move. His debauched bumps and grinds as he speaks, often fucking the air, punctuate his hilarious pigspeak with a new earthiness. He’d never seemed more human—which is to say funnier, more vulnerable—than playing a man without the self-awareness to know that barking the words “you are gonna give me that cherry pie sweet mama baby” might make him come off dopey, pathetic, and sad. We’ve never seen Cruise this lewd, and thus we’ve never really seen him get his hands dirty, dirty with the dopiness of desire. As my upstanding mother said when she called last night to tell me why she’d walked out of “that horrible, horrible

Magnolia”

and wanted me to explain what’s wrong with movies today, she sighed, “I’ll never be able to look at Tom Cruise again.” I didn’t have the heart to tell her that I feel like I’ve seen him for the first time.