The Penguin Book of Card Games: Everything You Need to Know to Play Over 250 Games (3 page)

Read The Penguin Book of Card Games: Everything You Need to Know to Play Over 250 Games Online

Authors: David Parlett

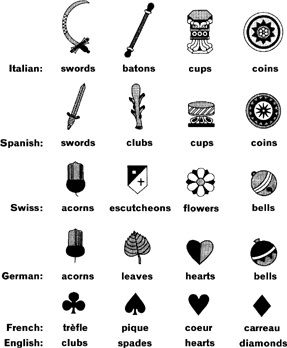

Six basic types of European playing-card systems are shown in

the accompanying table. You don’t have to learn them in order to

use this book, as al wil be explained as and when necessary. But

you may find the fol owing notes of interest.

The word spade probably represents the Old Spanish spado,

‘sword’, while club is a direct translation of basto, implying that

Spanish suits were used in England before the French ones were

invented (around 1490). The bel s of German and Swiss cards are

hawk-bel s. The situation is complicated by the fact that some

German games are played with French-suited cards but of a German

design and with German names ( = Kreuz, = Pik, = Herz,

= Karo, with courts of König, Dame, Bube).

The oldest court cards were al male. Cabal o and caval o mean

‘horse’, but, as they refer to their riders, are bet er termed cavaliers.

Ober/Over and Unter/Under are taken to mean, respectively, a

superior and inferior of icer, but original y referred to the position

of the suitmark. It has often been pointed out that Latin suits and

courts are military, Germanic ones rustic, and Anglo-French ones

courtly in nature.

Above Major European suit systems showing probable lines of

evolution from earliest and most complex to latest and simplest.

Below Each system has its own courts (face cards) and range of

numerals. Packs often appear in a shortened version (omit ed

numerals in brackets).

nation

length courts

numerals

Italian

52, 40 King Cavalier Soldier (10 9 8) 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

Spanish

48, 40 King Cavalier Valet (9 8 7) 6 5 4 3 2 1

Swiss

48, 36 King Over Under

Banner 9 8 7 6 (5 4 3) 2

German

36, 32 King Ober Unter

10987(6)2

French

52, 32 King Queen Valet

10 9 8 7 (6 5 4 3 2) A

International 52

King Queen Jack

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 A

The numerals are not complete in al traditions. Most French

The numerals are not complete in al traditions. Most French

games are played with 32 cards (formerly 36), Spanish and Italian

with 40, sometimes 48, rarely 52. Most Spanish and Italian games

omit the Tens, and the Ten is replaced by a Banner in Swiss games.

Aces are merely Ones in Spanish and Italian games. The Swiss

equivalent of an Ace, although so cal ed, is actual y a Deuce, as it

bears two suit-signs.

Plan of attack

I have made a heap of all I have found.

Nennius, Historia Brittonum

Most of the games are accompanied by a ‘working description’,

which means enough of a description to enable you to play the

game in its most basic form.

This is not the same as the so-cal ed ‘of icial rules’ of play. For

one thing, such rules include detailed instructions on how cards

should be shuf led and cut, what to do if someone deals out of turn

or exposes a card while dealing, etc., and there isn’t enough room

to be fussy about such niceties. For another, most games are played

informal y and are not equipped with of icial rules. Of icial rules

are drawn up for games played at tournament level, and should be

regarded as the of icial rules of the appropriate governing body, not

the of icial rules of the game itself. The vast majority of card games

are not book games but folk games. As such, they are played

informal y, without reference to books, by schools of players who

are quite able and wil ing to make up rules to fit whatever disputes

may arise (referring, if necessary, to the local oldest inhabitant as a

final arbiter), and to inject new ideas into the game that may, with

time, eventual y cause it to evolve into something else. The proper

time, eventual y cause it to evolve into something else. The proper

function of a card-game observer and col ector lies in describing

how games are played rather than in prescribing how they should

be played. Far too many card-game books have been perpetrated

by writers who, being primarily Bridge-players, imagine that the

only true way of playing every other card game is to fol ow what

was writ en about it in a book whose original text may be a

hundred years out of date. (And that’s no exaggeration. Nearly al

descriptions of Brag published in the twentieth century describe

only the nineteenth-century game.)

Since many games are played in dif erent ways by dif erent

schools, or even by the same school at dif erent times, I have

restricted my descriptions to the most basic form, and have marked

additional or alternative items as variations.

In some cases I have given a sample deal and made suggestions as

to skilful play, but this is not the primary function of the book,

which is designed to be extensive rather than intensive in its

coverage. I have preferred to devote space to introductory notes on

the historical and ethnic background of the game in question, since,

unlike skilful play, this is not something you can pick up for

yourself as you go along.

The col ection is divided into two dozen chapters, each covering

a group of similar or related games. This has necessitated classifying

card games according to their various methods of play, which may

be introduced and explained as fol ows.

Trick-taking games

The vast majority of European card games are based on the

principle of trick-play. Each in turn plays a card to the table, and

whoever plays the best card wins the others. These cards constitute

a trick, which the winner places, face down, in a winnings-pile

before playing the first card to the next trick. The ‘best’ card is

usual y the highest-ranking card of the same suit as the card led –

that is, of the first card played to it. Anyone who fails to ‘fol ow suit

to the card led’ cannot win it, no mat er how high a card they play.

to the card led’ cannot win it, no mat er how high a card they play.

Winning a trick is therefore doubly advantageous, since you not

only gain material but also have free choice of suit to lead next. If

you lead a suit which nobody else can fol ow because they have

none of it left, you wil win that trick no mat er how low a card

you play.

The trick-playing principle can be varied in several ways. The

most significant is by the introduction of a so-cal ed trump or

‘triumph’ suit, superior in power to that of the other three, the non-

trump or ‘plain’ suits. If, now, somebody leads a plain suit of which

you have none, you can play a trump instead, and this wil beat the

highest card of the suit led, no mat er how low your trump card is.

Trick-games vary in many dif erent ways, and in this book are

arranged as fol ows.

Plain-trick games Trick-taking games in which the object is to

win as many tricks as possible, or at least as many tricks as you bid,

or (rarely) exactly the number of tricks you bid.

1. Whist, Bridge, and related partnership games with al cards

dealt out. Most are games of great skil .

2. Solo Whist and other games resembling Whist-Bridge but

played without fixed partnerships, so everyone finishes with a

score of their own.

3. Nap, Euchre and others in which not al cards are dealt out, so

that only three or five tricks are played. Many of these are

gambling games.

4. Hearts, and relatives, in which the object is to avoid taking

tricks – or, at least, to avoid taking tricks containing penalty

cards.

5. Piquet, and other classic games in which the aim is both to

win tricks and to score for card-combinations.

6. Pitch, Don, Al Fours, and other members of the ‘High-low-

Jack-game’ family.

7. A miscel any of point-trick games including Manil e, Tresset e

and Trappola.

8. Skat, Schafkopf and other central European games of the ‘Ace

8. Skat, Schafkopf and other central European games of the ‘Ace

11, Ten 10’ family.

9. Marriage games. These are ‘Ace 11’ games that give an extra

score for matching the King and Queen of the same suit, the

best-known being Sixty-Six.

10. Bezique, Pinochle, and other ‘Ace 11’ games in which scores

are made not only for marriages but also for the out-of-

wedlock combination of a Queen and Jack of dif erent suits.

11. Belote, Jass and other marriage games in which the highest

trumps are the Jack and the Nine.

12. An eccentric family of northern European games derived from

a medieval monstrosity cal ed Karnof el.

13. Tarot games, in which trumps are represented by a fifth suit

of 21 pictorial cards. Tarots were original y invented as

gaming materials, not fortune-tel ing equipment, and

hundreds of games are stil played with them in France,

Germany, Italy, Austria and other European states.

There is room here only for a smal but representative selection.

Non-trick games

Games based on principles other than taking tricks are arranged as

fol ows.

Card-taking games Games in which the aim is to col ect or

capture cards by methods other than trick-taking.

14. Cassino, Scopa and other so-cal ed Fishing games, inwhich

cards lying face up on the table are captured by matching them

with cards played from the hand.

15. A variety of relatively simple capturing games such as Gops,

Snap, and Beggar-my-Neighbour, of which some (but by no means

al ) are usual y regarded as children’s games.

Adding-up games

16. Games in which a running total is kept of the face-values of

cards played to the table, and the aim is to make or avoid making

cards played to the table, and the aim is to make or avoid making

certain totals. The most sophisticated example, Cribbage, also

includes card-combinations.

Shedding games These are games in which the object is to get rid

of al your cards as soon as possible.

17. Newmarket, Crazy Eights and others, in which the aim is to

be the first to shed al your cards.

18. Durak, Rol ing Stone and others, in which it is to avoid being

the last player left with cards in hand.

Col ecting games Games in which the aim is to col ect sets of

matched cards (‘melds’).

19. Rummy games, and others, in which the aim is to be the first

to go out by discarding al your cards in matched sets.

20. Rummy games of the Canasta family, in which it is to keep