The Pentagon: A History (14 page)

Read The Pentagon: A History Online

Authors: Steve Vogel

As for the building in Arlington, Roosevelt said, it was perfectly suited for another pet project of his: He wanted a central home for the old files that now used up space in government offices around Washington. He had millions of records in mind, ranging from the individual files of three million Civil War soldiers to the public-land records charting the development of the great West to obscure State Department consular reports on the history of Mongolian ponies. “So I hope that this new building, when this emergency is over, will be used as a records building for the government,” Roosevelt said.

The controversy over the new War Department building was settled, the president concluded: “Now this takes care of it entirely.”

The whole thing is all up in the air

No one could imagine that Somervell would keep fighting. A round of self-congratulations followed among his opponents. The

Star

called the president’s action “highly gratifying,” and

The Washington Post

likewise claimed a share of victory. “As one of the institutions which joined heartily in the fight against the erection of a monstrosity on the south shore of the Potomac, The Post hails this compromise as a triumph for rational planning,” the paper wrote.

Presumably, Somervell had learned a good lesson, Hans Paul Caemmerer told a colleague. “Since Somervell says he is ‘a bricklayer’…it seems to me it would have been far better if in the beginning he had come…to our Commission or your Committee to ascertain what is appropriate in the way of a building for the National Capital,” the Fine Arts secretary wrote.

That was not the lesson Somervell had drawn. The general reported to the White House that he and Bergstrom had new plans ready for the president. Roosevelt’s uncle, Frederic Delano, and Harold Smith were likewise anxious to see the president to talk about the building. Roosevelt promptly summoned both sides to the White House on August 27, the morning after his press conference, to hash out the final details. Delano and Bergstrom arrived carrying large packages of blueprints and plans, and all four men assembled with the president in the Oval Office for the 11:30 meeting.

Roosevelt briefly reiterated what he had said the day before, that he wanted to put the building on the quartermaster depot site, and at half the size previously envisioned. Rather than a soldier receiving his president’s instructions, Somervell acted as if he were a visiting premier negotiating a treaty. The general staunchly insisted that the War Department should be built on the Arlington Farm site and told Roosevelt that his selection of the quartermaster depot site was unwise. Somervell also argued that the size of the building should not be reduced. Roosevelt seemed amused by Somervell’s persistence. “Of course you understand that I am commander-in-chief of the Army and Navy,” Roosevelt said, laughing as he spoke.

After a few minutes, Roosevelt instructed the men to adjourn to the adjoining cabinet room and iron out their differences among themselves. An hour’s discussion proved fruitless. Somervell would not budge. Somewhat dazed, Fred Delano emerged from the White House and spoke to reporters. “The whole thing is all up in the air,” he said. “The Army is holding on to its original proposal both as to size and location.”

Somervell at first refused comment, but when told of Delano’s statement, he remarked, “That’s a proper way of stating it.” The general then added his favorite stock reply: “But why talk to me about it—I’m just a bricklayer.”

Though the president’s declaration had left him with few cards to play, Somervell managed with bulldog stubbornness to carve out some negotiating room. The talks resumed in the afternoon at Delano’s office in the Interior Building. Delano drafted an agreement that limited the building to 15,000 people. Somervell strongly objected—he wanted space for 35,000—and both sides exchanged angry crossfire.

Delano persuaded Somervell to make a counteroffer on paper. “What would you insist upon?” Delano asked Somervell. “What is your position?”

Somervell sat down for an hour to write out his stipulations in pencil. He was willing to accept the quartermaster depot site but was holding out for a larger building. After three hours of back and forth, they broke for the day.

Consulting with McCloy the next day, Somervell lamented the avalanche of “unfortunate” publicity that had accompanied his defiance of Roosevelt. The general continued his talks with Delano that afternoon, agreeing to come down from his 35,000 figure. The two negotiated the language of the agreement—practically a treaty—working until late to have it ready for the president the following morning. At first glance, the three-page memorandum looked like a defeat for Somervell, as it provided for a building for twenty thousand workers on the quartermaster depot site.

But the language in the agreement was curious. It said the “general area” of the quartermaster depot site was acceptable as a home for the War Department, leaving Somervell quite a bit of wiggle room as to exactly where he put the building.

As for the size of the building, Somervell arranged even more leeway. The agreement said “the office personnel space should be limited to that for 20,000 persons at 125 square feet per person until it has been demonstrated that traffic facilities are sufficient to handle a greater number of employees.” While the language meant that the building would initially have 2.5 million square feet of office space, it did not mean that Somervell could not build a significantly larger building and later convert additional area into office space. Nor did it specify who would determine when the roads and bridges were sufficient to handle more than twenty thousand people.

In deference to Roosevelt’s wishes, the agreement stipulated that “the solution proposed is not advanced as a permanent location of the War Department, but one dictated by requirements of space and speed in the present emergency. The solution proposed does not exclude in any way the return of War Department personnel to the District of Columbia after the emergency, in which case the proposed building can be used for other offices, archives and activities if so desired.”

The agreement—with spaces awaiting the signatures of Stimson, Delano, and Smith—was presented to Roosevelt the morning of August 29. “It is a compromise,” Delano told reporters. “The Army will get some of the things it wanted and we will get some of the things we wanted. It is up to the president.”

For his part, the president was exasperated by the drawn-out battle. “I am going out to look at it,” Roosevelt announced that morning. He would examine the quartermaster depot site himself later that day, accompanied by the warring parties, and make the final decision.

I’m still commander-in-chief

The president’s limousine was waiting behind the White House, its top down. The weather on the late summer day was unseasonably mild, splendid for an open-air afternoon jaunt to Virginia to look over the real estate.

Gilmore Clarke had received a phone call at his office in New York that morning, August 29, asking him to report to the White House by four o’clock that afternoon. The Commission of Fine Arts chairman flew to Washington, hurried to the White House, and was directed to the back, where he found Smith and Somervell waiting.

Clarke introduced himself to Smith and then looked at Somervell, who gazed at his shoes and pointedly offered no greeting. Clarke had the gloating air of a teacher’s pet picked to sit at the head of the class. “General, you’re acting kind of childish, aren’t you?” he said.

Somervell studiously ignored the Fine Arts chairman. “Well, I thank my lucky stars I’m not in uniform, of a rank lower than you are, or I’d probably be behind bars,” Clarke continued. Somervell’s glowering intensified.

Shortly after finishing a two-hour cabinet meeting, Roosevelt rolled out the back of the White House in his wheelchair. Fala, FDR’s black terrier, trotted behind. The president, sporting a new plaid tie, headed toward his waiting open-air car, where two Secret Service agents lifted him from his wheelchair into the back seat in the right-hand corner. Fala hopped into a jump seat in front of the president. Roosevelt beckoned Clarke to sit next to him. Somervell climbed into the back on the other side, while Smith took the front passenger seat. Delano, unable to attend, sent Jay Downer as his representative, and the consultant boarded a second car with Bergstrom and Pa Watson, Roosevelt’s military aide.

At 4:25, the party left the White House grounds. Roosevelt, eager to see traffic conditions for himself, had chosen the height of the evening rush hour for the excursion. The limousine passed along the Tidal Basin, where John McShain’s crews had almost finished the Jefferson Memorial. Clarke had been steadfast in his biting criticism of the memorial, but Roosevelt could not resist proudly pointing out the pantheon design he had personally approved.

“Gilmore…don’t you like it?” the president asked.

“No sir,” replied Clarke, ever the scold. “I don’t like it. It’s a disappointment to all of the members of the commission.”

“I don’t know what we’re going to do with you fellows,” Roosevelt sighed.

As the entourage took the 14th Street Bridge across the Potomac, Somervell made a final appeal to the president for the Arlington Farm site, speaking across Clarke as if the commissioner were not even in the car. Moving the War Department building from Somervell’s favored site would delay the project and add millions to the cost, the general reminded the president.

Roosevelt’s face flushed with annoyance as Somervell spoke. “My dear general,” he said, leaning in front of Clarke and addressing Somervell. “I’m still commander-in-chief of the Army!”

This time, Roosevelt did not seem to be joking. Somervell retreated into silence.

They arrived at the site. It was known locally as Hell’s Bottom, and it looked it, a tawdry neighborhood of shacks, dumps, beat-up factory buildings, railroad yards, and pawnshops. Roosevelt liked it just fine. The car stopped at a spot on the southern edge of the property, and Secret Service agents jumped out and surrounded the car. Roosevelt pointed north to the site. “Gilmore, we’re going to put the building over there, aren’t we?” the president asked Clarke.

“Yes, Mr. President,” Clarke dutifully replied.

“Did you hear that, general?” Roosevelt continued. “We’re going to locate the War Department building over there.”

Somervell had no choice but to acquiesce.

When Clarke asked about the language in the congressional bill specifying the Arlington Farm site, Roosevelt dismissed the concern, confident his solution legally circumvented the law. “Never mind, we’re not going to pay any attention to that, we’re going to put it over here,” he said.

Inspecting the site at close range, Roosevelt pronounced it excellent. To get a better perspective on the eighty-seven-acre tract, the party continued to a high bluff along Arlington Ridge Road overlooking the site.

Even from up high, it was not a pretty sight. “It was pointed out that the industrial slums along Columbia Pike would mar the environment of the new building, and the President said they ought to be acquired,” Downer reported to Delano. Looking to the south of Columbia Pike, Roosevelt asked what could be done about the old brickyards and other properties in that area. Somervell said he was confident the Army could secure the authority for cleaning up the south side to a depth of several hundred feet. It was also agreed that what Downer called “slum dwellings”—actually a respectable black neighborhood known as Queen City—in a triangle of land framed by Columbia Pike and Arlington Ridge Road would be condemned for highway improvements.

Roosevelt wanted to know about the size of the building. Somervell replied that the gross area of the new building would be about four million square feet, or about four-fifths the size originally proposed. But in keeping with the agreement hashed out with Delano and Smith, Somervell promised the president it would hold no more than twenty thousand workers until it was demonstrated that the highways and bridges could handle more.

The entourage rode through Arlington Cemetery, past the Tomb of the Unknown Soldier, and back down toward Memorial Bridge, not even slowing as they passed the stately Arlington Farm site where Somervell had come so close to constructing the building. They drove back onto the White House grounds about an hour after departing. As the car came to a stop, Roosevelt again addressed Somervell: “General, you’re going to show the plans for this proposed building to the Commission of Fine Arts, are you not?”

Somervell had no intention of doing this, and told the president so. The general insisted the new location—certainly not part of L’Enfant’s monumental Washington—was outside the commission’s jurisdiction.

Irritated, Roosevelt waited until Somervell had finished. “Well, General, you show the plans to the Commission of Fine Arts and, when they’ve approved of them, show them to me.” Clarke listened delightedly. Once that caveat was met, FDR added, the project should “go ahead at full speed.”

With that, the president rolled back into the White House for a cocktail.

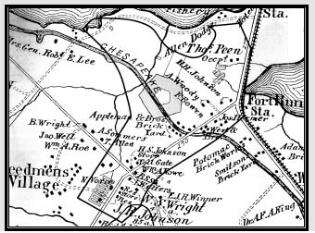

1878–79 Hopkins map showing the Lee mansion and environs, with overlay of modern Pentagon military reservation.