The Pentagon: A History (26 page)

Read The Pentagon: A History Online

Authors: Steve Vogel

More than in previous American wars, command would be directed from Washington. In World War I, much of the War Department general staff had been headquartered in France, relatively near the action. This war, with American forces spread around the world, would be different, Marshall told Marvin McIntyre, a White House aide. “Today, due to the fact that we have a number of overseas theatres and are engaged in a colossal program of military material

for our Allies,

all of the responsibilities of the War Department of the first World War…have all centered here,” Marshall wrote.

“We have got to a point where we are actually impeded in our war effort due to the fact that the offices of the War Department are so widely scattered,” assistant secretary of war McCloy warned eight weeks after Pearl Harbor.

In late January, Roosevelt asked White House aide Wayne Coy to check with the War Department about progress of the Pentagon building. Somervell’s pre-Christmas demand that one million square feet be ready by April 1 seemed now to be an April fool’s joke. The time lost because of the design changes, the debate over bomb-protection—the sheer impossibility of the goal in the first place—led to some recalculations. Renshaw was willing to promise that a larger amount of space—1.3 million square feet—would be ready, but not until June 1. Groves altered the prediction, promising 500,000 square feet by early May, which was what Somervell had originally promised when work started. Word was relayed to the president. “The first part of the building will be ready for occupancy in early May,” Coy reported to Roosevelt. The entire building would be finished by November 15.

It would not be a moment too soon. Predictions were that the War Department, which now numbered 25,000 workers, would have 50,000 employees in Washington by July 1. Big as Somervell was building the Pentagon, it was not going to be big enough.

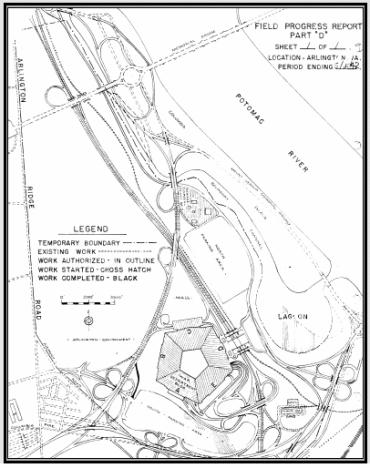

Construction field progress report, May 1942.

An overwhelming task

The concrete edifice rising from the low ground to the east could be seen plainly through the dreary winter morning light, and the percussion from the pile drivers floated up the hillside to the gravesite at Arlington National Cemetery. Somervell had personally chosen the location, about a hundred yards down the hillside from L’Enfant’s tomb and the Lee mansion. It was a lofty spot, benefiting from the magnificent vista that had been spared when Franklin Roosevelt ordered Somervell to build his headquarters downriver. Shortly before noon on Tuesday, January 27, 1942, an Army burial team carried the casket with the remains of his wife, Anna Purnell Somervell, to the grave awaiting in the wet ground.

Connie Somervell, fifteen, watching with her father and two older sisters, tried to stop crying but could not. Down at St. Margaret’s, the boarding school she attended in the Tidewater area of Virginia, Connie had known little—only that the illness that had slowed her mother over Christmas had taken a grave turn. First it was thought to be a bad cold. Pinned down with work in January and spending his nights at his apartment in Washington, the general fretted about his wife, suffering with no one to care for her at the tobacco farm in southern Maryland. He arranged to check her into Walter Reed Army Hospital in Washington, where doctors found she was suffering from a staph infection that had developed into blood poisoning. “I used to write her everyday, then my older sister said, ‘Don’t bother writing mother, she can’t read your letters,’” Connie Somervell Matter recalled. “When you’re fifteen, you don’t believe your parents are going to die. I was distressed, but I presumed she was going to get well.” On Sunday night, January 25, Anna Somervell died at Walter Reed at age fifty-seven.

General Marshall was informed the following morning and sent a note to Somervell at the tobacco farm: “I just learned a moment ago that Mrs. Somervell died last night, and I want you to know that you have my deep sympathy…. The fact that I have burdened you with an overwhelming task at a time when you were suffering a personal tragedy, makes me feel all the more solicitous of your welfare.” A few days later, Henry Stimson personally awarded Somervell the Oak Leaf Cluster for his Distinguished Service Medal, this time honoring his work as chief of the Construction Division. Somervell had overseen “the greatest building program of modern times” and done it in “record-breaking time,” the citation noted. “I am very glad that this trifle of encouragement and recognition of his superb services has come to him at this time,” Stimson noted in his diary.

The loss of the Red Cross volunteer he had brought home from Germany after World War I, a doting and graceful mother who adored her husband, profoundly saddened Somervell. “He was devastated,” Connie Somervell recalled. Yet it slowed him not in the least. In the days before and after his wife’s death, Somervell was busy engineering another rise to power. Unlike his machinations the previous summer and fall, this effort would prove more fruitful.

Somervell’s rise was perhaps inevitable, once peacetime niceties were cast aside. War had a way of bringing his like to the fore. Four days after Pearl Harbor, Stimson, concerned about the “tremendous burdens” on Marshall’s shoulders, privately advised the chief of staff that “it was time to pick out young men [with] outstanding brains and character and bring them forward.” Somervell was one of three names Stimson mentioned; Marshall agreed.

Marshall, fed up with an archaic administrative system that divided much of the Army into fiefdoms, already had in mind a radical reorganization to streamline the War Department headquarters. His ability to make quick decisions was crippled by the need to consult with myriad bureaus and commands that tended to jealously guard their prerogatives. Seizing on the opportunity presented by the shock of Pearl Harbor, Marshall moved quickly to do away with much of the headquarters apparatus, cutting the number of officers who had direct access to the chief of staff from more than sixty to six.

Learning in January of Marshall’s intention, Somervell immediately got to work influencing developments. He advanced his own plan in February to create a unified supply command, combining disparate bureaus and agencies into one organization that controlled all equipment, construction, supply, and transportation. It fit perfectly with Marshall’s vision. Somervell was not shy about suggesting he was the logical choice to head this massive new command. Marshall and Stimson agreed.

On February 28, Roosevelt signed an executive order reorganizing the War Department and dividing the Army into three major commands. Lieutenant General Leslie J. McNair was appointed commander of all Army ground forces, Lieutenant General Henry “Hap” Arnold, commander of all Army air forces, and Somervell, newly promoted to lieutenant general, commander of all Army supply forces. In effect, all of the Army not directly involved with combat now reported to Somervell. Training of troops, communications, military justice, chaplains, quartermasters, engineers, and ordnance, among many other areas, were now part of Somervell’s domain. To Somervell fell the task of supplying eight million soldiers scattered across the globe with weapons, bullets, food, shoes, uniforms, medical care, and transportation. “In military annals not even Napoleon’s quartermaster could approach the magnitude of the job he had to do,”

The New York Times

wrote.

“I will say this for General Somervell,” a wary Harry Truman told fellow senators, “he will get the stuff, but it is going to be hell on the taxpayer.” Truman was right on both counts.

At the suggestion of Marshall, who wanted him “handy,” Somervell moved from his tobacco farm into Quarters Two at Fort Myer, a stately redbrick home next to Quarters One, the home reserved for the chief of staff. Somervell’s eldest daughter, Mary Anne, a chemist with the Bureau of Standards, moved in with her father and ran the household, planning menus and seeing that her father’s uniforms were pressed. She would breakfast with him at seven o’clock—the eighteenth-century oval mahogany table set with gold-rimmed service plates bearing the Somervell family crest, and a pot of tea at the general’s place—before he rushed out the door.

Somervell soared to national prominence. Within weeks, he was on the cover of

Life

magazine, and soon after that,

Time.

He spoke to war workers around the country and with typical flair braced Americans for the sterner realities of war. “Hitler and the Japs aren’t interested in the forty-hour, fifty-hour, or sixty-hour week,” he told two thousand cheering factory workers in Yonkers.

In little over a year, Somervell had risen from lieutenant colonel to three-star general, a climb surpassed in speed only by a few, among them Eisenhower. In the process, he had leapfrogged in rank over dozens of more senior officers. (He was only forty-nine, but, knowing Marshall’s penchant for younger generals, Somervell played it safe and did not tell the chief of staff he would turn fifty in May.) Major General Reybold, who as chief of engineers held the job Somervell had so desperately coveted, was now below Somervell in his new command. Likewise Major General Gregory, the quartermaster general who had taken quiet pleasure at Somervell’s comeuppance, now found himself reporting to his former subordinate.

Somervell was again directing all Army construction, now from a much higher level. Hundreds of camps, airfields, and depots needed to be built across the country and around the globe, so many as to make the tremendous $2 billion effort he directed the previous year look like a pittance. From December 7, 1941, until the end of February 1942, the Corps of Engineers was launching construction projects costing an unheard-of $200 million a week. In March, when Somervell assumed his new post, the figure reached $250 million a week.

“The undertaking was truly gigantic, dwarfing those previous great endeavors, the building of the Panama Canal and the emergency construction programs of 1917–18 and 1940–41,” Fine and Remington wrote in their official account of Army construction in World War II. “In urgency, complexity, and difficulty, as in size, it surpassed anything of the sort the world had ever seen. The speed demanded, the sums of money involved, the number and variety of projects, the requirements for manpower, materials, and equipment, and the problems of management and organization were unparalleled. So formidable was the enterprise that some questioned whether it was possible.” It would be, as Somervell immodestly but perhaps not incorrectly later called it, “the most brilliant chapter in world construction history.”

Among many other responsibilities, Somervell was officially back in charge of the Pentagon construction. Of course, he had never really relinquished control of the project, but now the chain again led directly to him, and he wasted no time exercising his authority.

On March 25, Somervell sent a short memo to Reybold that the chief of engineers, knowing Somervell as he did, could only have read as ominous. “The occupancy of the new War Department must be assured at the earliest possible date,” Somervell wrote. “I am counting on your personal efforts to see that this is done and in any event that occupancy may be begun on May 1.”

The next day, Colonel Frederick Strong, a veteran engineer and trusted aide to Somervell, passed the message on to Groves. “General Somervell and I discussed your ‘big building,’” Strong told Groves. There could be no retreat from the deadline: “On account of commitments made to the President and the Chief of Staff, the above schedule will have to be carried out despite all obstacles.”

Just when it looked as if winter was over and that McShain and Renshaw could count on some decent weather, a Palm Sunday storm on March 29 dumped eighteen inches of snow on Washington. The blizzard left whole sections of the city blacked out, paralyzed the region’s roads, and slowed work at the job site, but it did not stop Somervell from showing up at his office first thing the following morning and sourly looking over his staff with a gimlet eye: “Which one of you sons of bitches remarked that spring was here?”

From the bottom of the Potomac River

Slipping past Alexandria and looking upriver, the captain of the night tug noticed with a start that the dome of the Capitol was blacked out. It had been darkened ever since Pearl Harbor several months earlier, but after fifteen years working the Potomac River, he was still shocked every time he saw the familiar beacon was missing.

Inside the dark pilothouse, the captain gently turned the wheel. A light drizzle began falling, further darkening the night and blurring the remaining lights on the inky shore. Upriver, the captain could see the flashing green buoy at Hains Point, where the Anacostia River flowed into the Potomac. He noted the location with a cross in his mind. “Cross marks spot where the battle begins tonight,” the captain muttered.

The tug was pulling two barges, both heavily laden with gravel. The captain wanted to deliver the gravel upriver to a concrete plant in Georgetown, where he knew it would fetch good money. Builders were desperate for concrete to finish half-built apartments, roads, and houses all around Washington. But the War Department was buying almost every ounce of gravel dredged from the Potomac, feeding the insatiable appetite for concrete to build the Pentagon. The captain would have to get past McShain’s concrete batching plant in the old airport lagoon, where Army officers kept a keen eye on the river, ready to motor out in a launch to intercept any load of gravel that—by virtue of wartime materiel priorities—they could claim.

The captain had ordered his crew to darken the tug as much as possible. Lanterns were kept off the deck and the portholes blacked out. The doors to the engine room were shut. It was futile, perhaps, since he had to keep his green-and-red navigation lights on. But every little bit might help. This could be the night he slipped past, the captain thought, but then he stopped himself. “Oh, I always think that.”

On board the tug listening to the captains was Charles E. Planck, a forty-four-year-old Kentucky native, an aviation writer with a keen eye who had taken a job with the Civil Aeronautics Administration as an information officer. Planck watched as the captain swung wide around the buoy at Hains Point, calculating his turn with an expert eye, and then braced himself for the final run up the river. “All the trip had led up to this one ten minutes,” Planck wrote in an account of the unnamed captain’s journey.

“He watched the southern shore,” Planck continued. “He wished his navigation lights could be doused. He wished his engine would breathe a little more quietly. He even wished that little gray launch which represented defeat to him might suddenly lose a bottom plank from stem to stern and sink in two minutes.”

The tug slipped under the 14th Street Bridge, just below the lagoon. There was no sign yet of the launch, and for a moment the captain again had hope. Then he spotted a small, dark-gray vessel nosing out from the mouth of the lagoon. “He could see the faint white plume of its wake as it headed straight for him,” Planck wrote. “Soon he heard the little bump as it came alongside and then the officer’s shoes hit the deck. He gritted his teeth as he heard the man’s feet on the ladder rungs and saw his face dimly as it came up into the pilot house.”

The officer’s genial greeting broke the silence. “Howdy, captain,” the officer said. “Guess we can use these two loads.”

The War Department could indeed use it. The need was inexhaustible. Concrete was being poured on a scale never seen for a building—410,000 cubic yards would be required for the Pentagon compared to 62,000 for the Empire State Building.

The location chosen to construct such a building was a wise one, from the standpoint of the basic ingredients needed. Just south of the site, beneath the waters of the Potomac and below a layer of soft mud, lay a boundless supply of sand and gravel. The melting of glaciers when the Ice Age ended fifteen thousand years ago had turned the Potomac into a vast waterway carrying enormous volumes of both materials. The glacier melt left gravel deposits up to eighty feet deep beneath the bed of the Potomac near where National Airport was built, giving the area its name, Gravelly Point.