The Pentagon: A History (37 page)

Read The Pentagon: A History Online

Authors: Steve Vogel

An aerial photo from 1944 shows the finished Pentagon. (U.S. Army)

Hundreds of soldiers sort through Army personnel records in one large basement office in this 1950 photograph. (U.S. Army)

Messengers use special tricycle carts to navigate the seventeen miles of Pentagon corridors. (U.S. Army)

Visitors check in with receptionists at big desks in the concourse. “The girls are selected for their good looks, brains, tact, and just ordinary horse sense, and many a male lingers at the counter,” a newspaper reported. (U.S. Army)

Groves was moving fast with the Manhattan Project, yet he was not done with the Pentagon. At their meeting September 17, he and Styer agreed that Groves would retain personal control of the Pentagon’s construction until the building was finished. The Pentagon project had such a high profile and “was of such great importance” to the Army that he could not drop it, Groves later wrote. “The impact on the reputation of the War Department and of the Corps of Engineers was tremendous.”

In part, keeping Groves in charge of the Pentagon was a security measure to avoid drawing attention to his assignment to the secret Manhattan Project. “My sudden disappearance from the work on the Pentagon would attract much more notice than would my absence from other Army construction activities,” Groves wrote.

The second reason was that the Pentagon project was “full of political dynamite,” and Groves was needed to handle Congress. “It would be better for me to continue to carry the responsibility for that job than to pass it on to someone else who was unfamiliar with its past problems and their many political ramifications,” Groves wrote. Another way of putting it is that Groves knew better than anyone where the skeletons lay at the Pentagon.

Somervell “very heartily approved” of keeping Groves in charge of the project. “I just told him bluntly that there was nobody there that I thought could handle Congress as well as I could, which he knew,” Groves later said.

They would not have to wait long to put Groves’s services to work.

One of the worst blunders of the war

The whole Pentagon project looked fishy to Albert Engel. He summoned Renshaw to his office on Capitol Hill on the morning of September 22 to explain various discrepancies he had uncovered, including how the $8.6 million for access roads and parking included in earlier progress reports had mysteriously disappeared by August. That figure, Engel calculated, should be added to the $49.2 million for the building proper, the $9.5 million being spent by the Public Roads Administration on access highways and bridges to reach the building, and $2.4 million being spent on landscaping. The public should be advised that they were pouring $70 million into a project of “doubtful value” instead of the $35 million initially promised, Engel told Renshaw. He was further incensed that the reports were all stamped confidential.

Engel had also homed in on the sweetheart deal with the two Virginia contractors. McShain was supplying more than 90 percent of the manpower for the job while Doyle & Russell and Wise had insignificant roles. It was obvious, Engel told Renshaw, that the Virginia contractors were on the project “purely for political reasons.”

Renshaw could barely get a word in edgewise. “Engel talked at me for two hours this morning,” Renshaw complained after the meeting. He raised the alarm at Construction Division headquarters that Engel was on a rampage.

For some reason, Groves had seemed “sort of disinterested” in construction business over the last few days, noted his aide, Major Matthias, who, like most officers in the Construction Division, knew nothing yet of the Manhattan Project assignment. However, the news about Engel got Groves’s attention in a hurry. “Groves is very much concerned about this,” Matthias told Renshaw that afternoon.

Renshaw replied that it would do no good to cover up the costs anymore. Engel, he had concluded, was “smart enough to know if you’re trying to withhold anything.”

Groves thought differently. He wanted the money being paid for outside architects and engineers—now about $1.6 million, or six times higher than estimated—deducted from the next Pentagon progress report. “He doesn’t think anybody will pick that up,” Matthias told Renshaw.

But it was too late for Groves’s number games. Representative Lane Powers, a New Jersey Republican Appropriations Committee member and Somervell confidant, spoke with Engel on the afternoon of September 22, trying to head off disaster. “Why don’t you give Bill Somervell a ring and sit down with him?” Powers suggested.

“I don’t owe Somervell a goddamned thing,” Engel replied.

Immediately after his conversation with Engel, Powers warned Renshaw that Engel was going to go public on the floor of the House with his investigation. “I think he’s going to probably get a half hour some day, and get up and just blow the whole thing,” Powers told Renshaw over the telephone. “[O]f course he can yank the thing around where it’ll make a hell of a good newspaper story.”

He was right about that. On Thursday, October 1, the congressman took the floor of the House, a shock of gray hair standing on end. In grim tones over the next forty minutes he outlined his findings: The Pentagon project would cost $70 million, twice what Congress had authorized, and the building had grown to a staggering six million gross square feet. The Virginia contractors, he continued, had done little to earn their fee of more than $200,000. The War Department had used censorship to cover up a “shameful squandering” of money.

Engel ridiculed the War Department’s claim that the amount of office space in the building was a military secret. “If there is going to be any bombing, the Japs certainly are not going to come over here and measure a building that covers 42 acres of ground before they start any bombing,” he said. “They are going to bomb it whenever they can and wherever they can.”

Engel placed the blame for the whole matter squarely on two men: Franklin D. Roosevelt and Brehon B. Somervell. “There is no evidence that the President has taken one step…to prevent some of the shameful waste of the taxpayers’ and bondbuyers’ money,” Engel declared. As for Somervell, Engel said, the general had “violated the mandate” of Congress by ignoring the cost limits.

Somervell’s reliable ally, Clifton Woodrum of Virginia, rose to defend the general and the president, as well as the Virginia contractors. But Engel gave no quarter. “He is known as a two-fisted, forthright debater, and yesterday he was unsparing in his denunciation of the Administration for the expenditures in connection with the War Department Building,” the

Washington Times-Herald

reported.

At Somervell’s order, Groves coordinated the response to Engel’s attack. Groves conferred with Renshaw and McShain to figure ways of refuting the claims. To his relief and amusement, Engel had not criticized him; indeed his speech praised Groves for his management of the project and said the building was well-constructed. Engel had figured out a lot but never realized Groves’s role in trying to hide the costs of the Pentagon.

Groves monitored the newspaper coverage, a key barometer of how much damage they had sustained. On the bright side, the New York papers largely ignored the affair. “The ‘New York Times’ gave but scant attention to the matter, on an inside page,” Groves informed Somervell. But all the Washington newspapers gave Engel prominent, front-page coverage, some with screaming headlines that the War Department had squandered millions of dollars and tried to squelch Engel’s investigation.

The day after Engel’s speech, Somervell—aided by Groves—composed a letter stoutly refuting the charges. It was quickly delivered to Woodrum, who rose in the House that afternoon brandishing the letter, declaring that it vindicated Somervell.

“I cannot agree that the War Department failed to keep faith with the Congress in respect to this building,” Somervell wrote. The letter noted that the general had warned from the start that moving the building from his preferred site at Arlington Farm would increase the $35 million cost. Further, Pearl Harbor had necessitated a bigger building. Somervell had informed the Appropriations Committee in May that the price of the building would be $49 million. Including the Virginia contractors had been necessary owing to the “size and complexity of the undertaking.” As for the secrecy that had surrounded the project, Somervell wrapped himself in a cloak of national security. “An alert enemy, and our enemies are alert, gains valuable information from the disclosure of facts not generally recognized as military secrets,” he wrote.

Finally, no one could now argue that the Pentagon was unnecessary. “The wisdom of the Congress in providing this building has been proven by the events of the past year,” Somervell concluded. “The efficiency of the War Department has been tremendously increased.”

Engel declared himself unimpressed. “He’ll have to do better than that to convince me I’m wrong,” he said. Somervell, Engel said, had displayed “an utter disregard” and “contempt” for Congress.

Yet there was no demand in Congress for further inquiry, nor did Engel request any action—for the time being, at least. Engel, Groves later wrote, “was a peculiar man. He enjoyed the respect of his colleagues in the House as a man of complete honesty, but he was also known as a man who started many things with a flourish and then abandoned them once his publicity had been achieved.”

Somervell’s response to Engel’s charges, also given front-page play, muted some but not all the public criticism. “It is to be doubted if Congress would have approved the building, had these costs been known then,” the

Evening Star

commented.

It was not just the price tag that was shocking. Everyone had known the Pentagon was big, of course. But until now, few had understood that Somervell had built a headquarters even larger than what had been proposed a year earlier. “The public was led to believe that the size of the building had been scaled down,”

The Washington Post

lamented in an editorial. “…Actually, however, the size of the building was enlarged even beyond its inflated proportions…. Congress was not asked to authorize this enlargement of the project. It has merely been informed of a

fait accompli.

”

This was entirely true. The newspapers were further shocked when Engel announced a few days after his speech that a fifth floor was being added to the Pentagon. Though that work had been under way since July and was now nearing completion, this was the first the press or public had heard of it. The War Department, after all, had labeled the space “fourth floor intermediate.”

It was all cause for heartburn. “Washington has many reasons to regret the construction of the gigantic War Department Building,” the

Post

editorialized. “…All our enemies know, of course, that the War Department has located a magnificent target just south of the Potomac.” The editorial included this prediction: “If the finished project is now to cost 70 million dollars, as Representative Engel charges, it may easily stand out as one of the worst blunders of the war period.”

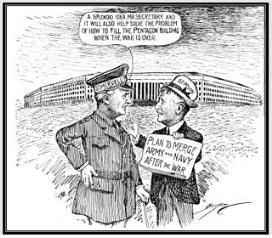

Clifford Berryman cartoon from the Washington

Evening Star,

April 1944.