The Pentagon: A History (4 page)

Read The Pentagon: A History Online

Authors: Steve Vogel

It was not to be. Several months after Pyle’s visit, Congress cut off all further funding for the canal, and the project was shut down. Somervell would have to make his mark elsewhere.

A gleam of light on the horizon

Somervell’s time in Florida was not entirely wasted. Among those he met in Ocala was a slim, somewhat wan former social worker from Iowa whose mild-mannered appearance completely belied the power he bore as confidante and alter ego of the president. Harry Lloyd Hopkins, the impassioned and resilient New Deal high priest leading the largest work-relief effort in the nation’s history, was impressed with Somervell’s performance putting thousands of men to work on the canal. When that enterprise collapsed, Hopkins saw Somervell as the ideal man to straighten the embarrassing New York WPA mess. Somervell cultivated his relationship with Hopkins, recognizing the aide’s tremendous influence with Roosevelt. Somervell’s accomplishments in New York over the next four years solidified a deep bond between the soldier and the social worker. More importantly, Hopkins appreciated what Somervell might still accomplish. Though by then terribly frail from a cancer operation that removed three-fourths of his stomach, Hopkins became Somervell’s great champion.

Somervell needed one. By the summer of 1940, he was agitating to get out of New York, worried he would miss the boat if war came and he was stuck at the WPA. For years, Somervell had believed another war with Germany was inevitable. (“If I hadn’t,” he said, “I would have got out of the Army long before.”) The stunning evacuation of British troops from Dunkirk in late May 1940 convinced him the time was near. Somervell began “frantically pulling wires” to get back on active service, pressing his case with a senior officer on Marshall’s staff.

La Guardia, by now a fervent believer in Somervell’s abilities, twice blocked his efforts to leave the city with appeals to the White House. Somervell used his own White House entrée to appeal directly to Roosevelt in October, arguing that the WPA was running smoothly and that he could better serve the country if he were back on military duty. After FDR promised La Guardia he would appoint a worthy successor, the mayor reluctantly agreed to Somervell’s departure. “It hurts,” a disappointed La Guardia told reporters when the news was announced November 7. Somervell, the mayor said, “leaves here permanent and impressive monuments to his executive skill.”

Leaving New York was only half the battle. Somervell’s performance did not earn him much credit among his peers in the Army, who held a low regard for the WPA and its decidedly unmilitary projects. Somervell spoke briefly with Marshall, asking to be considered for a field command and reminding the general of his highly decorated combat service in World War I. Marshall, though impressed with Somervell’s work building the airport in New York, was noncommittal. To his dismay, Somervell subsequently learned that the chief of engineers, Major General Julian Schley, who viewed Somervell as a bit too ambitious and a bit too shrewd, was assigning him to a respectable but lackluster position as executive officer for a new engineer training center to be established in the Midwest. No location had been selected yet, giving Somervell a reprieve.

Arriving in Washington in November 1940, Somervell began desperately fishing about for a better assignment. He need not have worried. Unknown to Somervell, Stimson and Marshall were watching him with another job in mind. The secretary of war, fretting over the Army’s camp-construction debacle, was impressed with what he saw. After meeting Somervell, Stimson wrote in his diary, “A gleam of light…came into my horizon.”

Waiting in the wings

Brigadier General Charles “Baldy” Hartman, chief of the Army’s Construction Division, had heard the rumors for a week that his head was on the block; stubborn, proud, and a bit nervous, he ignored them and went about his work. He was not surprised when his superior, Major General Edmund Gregory, showed up unannounced at the division headquarters in the Railroad Retirement Building on Capitol Hill early in the afternoon of December 11, 1940. “I knew by the scared look on his face he had bad news for me,” Hartman later said. He was right.

Being chief of construction was the culmination of a quarter-century of dedicated service for Hartman. He was a West Point graduate who had been one of the Army’s youngest colonels in World War I, and he was beloved by his staff for his honesty and modesty. But his timing was bad. He was appointed to the job in March 1940, just weeks before the national emergency prompted by the fall of France overwhelmed the Construction Division. “The Lord Himself could not meet the construction timetables and cost estimates,” reported a construction expert sent to assess the situation for the government. But that did not matter. Angered by the delay in the Army’s mobilization, Marshall’s staff complained that Hartman was “making a complete mess of the construction program.” Baldy, one critic said cuttingly, was a “nice old gentleman who was used to being bawled out by colonels’ wives over furnaces.” It was a cruel judgment, unfairly smearing an officer who in ordinary times would have been a fine construction chief. But Hartman’s best was not good enough, not now.

Marshall had come to Stimson’s office the morning of December 11 to tell the secretary he intended to replace Hartman with Somervell. Stimson felt a bit queasy about axing Hartman, despite his deep dissatisfaction with construction progress. “It is a pathetic situation because Hartman has been a loyal and devoted man,” he wrote in his diary that day. “…But he apparently lacks the gift of organization and he has been running behind in the work.” Stimson approved the change.

The pressure had been building for weeks. The White House had threatened to take the construction program away from the Army and put it under civilian control. Momentum for the move waned as soon as Army officials let the White House know that Somervell would be put in charge. That satisfied the critics. Harry Hopkins, in particular, gave Somervell an “enthusiastic” endorsement.

Gregory, who was the Army’s quartermaster general and who in theory should decide who would head the Construction Division, still balked at the switch, not out of loyalty to Hartman, but because he did not in the least trust Somervell, whom he considered “brilliant, but slick.” Marshall’s deputy chief of staff, Major General Richard C. Moore, warned Gregory that unless he accepted Somervell, the entire construction program would be stripped from the Quartermaster Corps.

Gregory finally saw the light. Arriving in Hartman’s office, he wasted no time with pleasantries and informed Baldy that he was relieved at once from the Construction Division. “I did not give him the courtesy of a reply,” Hartman later said. He closed his desk and left his office.

Somervell was waiting in the wings. “Somervell walked in one door, and Hartman walked out the other,” Hartman’s secretary later recalled. Somervell had been eagerly preparing since November, when a Stimson adviser had asked if he would be interested in the position; before the job was even his, Somervell had launched a “whirlwind” four-state inspection tour and produced a fourteen-page report criticizing the construction program.

Somervell’s appointment was announced to the press December 13; reporters were told the construction delays “had no bearing” on the change of command. Hartman checked himself into Walter Reed Army Hospital, on the verge of a nervous breakdown. It was curiously reminiscent of the fate that had befallen Somervell’s predecessor at the WPA. The War Department announced he had entered the hospital “for observation and treatment following a long period of overwork.” In part, it was a convenient fiction, Stimson noted in his diary, “designed to protect poor old Hartman, who has been as faithful as could be and has broken down under the task, from being unjustly criticized.” Hartman was indeed broken, as was his heart. He soon suffered coronary problems, retired, and cut off contact with old friends.

The deed done, it was soon forgotten, as Stimson was much enamored of his new construction chief. “Somervell was like a breath of fresh air,” the secretary recorded after the two talked the job over. Stimson proudly showed off his new construction chief at a press conference December 19, an appearance that had the desired effect: “I think the sight of Somervell was enough to show the point to the Press that progress was being made.”

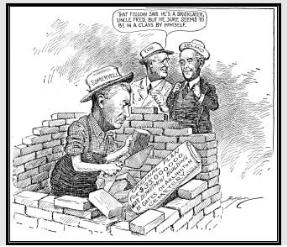

Clifford Berryman cartoon in the Washington

Evening Star,

August 29, 1941.

I will just move

The officers of the Army’s Construction Division filled a government auditorium near the division’s Capitol Hill headquarters on the morning of February 22, 1941. Though 120 had been invited and 150 chairs set out, the officers spilled over into the aisles. No one, it seemed, dared miss hearing the new chief speak about his principles of organization.

Brigadier General Brehon Somervell commanded the floor. “Napoleon used to say—I’m very glad he said it because I have repeated it two or three hundred times—‘There aren’t any poor regiments; there are only poor colonels.’” Somervell then drove home the point, in case anyone had missed it: “Everybody here is a colonel, in a sense.”

Doubtlessly, many officers shifted uncomfortably in their seats. After waiting a decade and a half during the slow interwar years to make lieutenant colonel in 1935, Somervell had jumped two ranks to brigadier general in January 1941, and he was not the least bit shy about using his new power. Since taking command of the Construction Division a little over two months earlier, Somervell had purged the organization, sweeping out Hartman loyalists, older officers who had lost their steam, incompetents, fools, or anyone else he concluded was not up to the job. It had become known as the Somervell Blitz.

“I will not talk…,” Somervell told Brigadier General Eugene Reybold, the Army’s chief of supply, a week after taking command. “I will just move.”

That he had done. The new construction chief filled key positions with his own men, bringing in engineers from his days at the New York WPA and the Florida Canal. With Marshall’s blessing, he raided other War Department staffs, trolling for the most aggressive officers and the smartest operators. Somervell streamlined the division, reducing it from eleven branches to five. “If he continued any of Hartman’s policies, it was purely coincidental,” a division officer later said.

The Somervell Blitz was more than a bloodletting. It was accompanied by record-breaking construction. Somervell pressed forward as if the nation were already at war, calling the Construction Division “the shock troops of preparedness.” He drove his staff relentlessly, seven days a week, leaving officers exhausted. “We members of the Construction Division in Washington had a major campaign under our belts before the shooting war for Americans got underway,” said Major Gar Davidson.

The first battle was to get the Army’s stalled mobilization moving. Dozens of camps were needed to house troops across the county by the spring. Workers fought bad weather and material shortages but quickly finished fifty major camps and twenty-eight troop reception centers. By spring 1941, they had finished enough facilities to accommodate the entire Army, now one million strong.

“The new Army is housed,” Somervell boasted in a press release. The tally under construction by the summer also included nine hospitals, forty-five munitions plants, fifty-two harbor facilities, ten chemical-warfare plants, and twenty-one storage depots. “In terms of speed it represents the most remarkable achievement in rapid large scale construction in the annals of this or any other army,” the War Department claimed.

A new story emerged, replacing the image of bumbling quartermasters from the previous fall. In this, Somervell took his cue from one of his heroes, Theodore Roosevelt. The Rough Rider had known the value of publicity, and so did Somervell. In his first week on the job, he created a new section in the Construction Division—public relations—and immediately hired a veteran newspaperman, George S. Holmes, a former Washington correspondent for the Scripps-Howard chain, to run it. Somervell ordered every construction office in the country to put public relations men on their staffs and supply the local press with regular stories about construction projects. They were instructed to send Holmes progress reports and photographs every Friday via airmail.

Holmes and his staff were soon putting out an “exuberant” flood of press releases extolling the accomplishments of the Construction Division and, by extension, Somervell. The effort paid off with national publicity, including a seventeen-page layout in

Fortune

magazine that told how “half horse, half alligator” quartermasters had “conjured forty-six cantonments and tent camps out of prairie mud or pine barrens or rocky defiles.” Somervell distributed thousands of copies of a forty-four-page booklet saluting “the greatest Army building program of all time.” He appeared at groundbreakings and construction-industry conventions around the country and wrote articles for industry publications saluting “this unparalleled achievement.”

Somervell handled congressional relations with equal aplomb. Hartman, his predecessor, had let congressmen cool their heels in the hallway when they came visiting. But anytime congressmen came calling, Somervell would sweep out anyone who happened to be in his office and usher in the legislators.

The support Somervell had from the top was more than Hartman could have imagined. Somervell, according to Quartermaster General Gregory, had a “pipeline to General Marshall,” and thus did not pay any attention to his nominal chain of command—including Gregory. The quartermaster general watched sullenly as his subordinate was granted his every wish.

Somervell had another trump card, one that intimidated his rivals even more than the unstinting backing he received from Marshall: Harry Hopkins. Every senior officer in the department knew the president’s closest aide was Somervell’s protector. If they didn’t, Somervell let them know. Gregory believed Hopkins “was always moving around back of the curtain.” How true this was did not matter. The perception was daunting enough.

For Somervell, it was a perfect situation: an unlimited mandate to build, coupled with unlimited power and an unlimited budget. “You can’t do anything without money,” he told the Construction Division officers gathered in the auditorium on that February morning. “It may be the curse of humanity but we all like to be cursed every once in a while.”

Somervell was amply cursed. The Army’s earlier cost estimates for the construction program had been woefully inadequate, and Somervell had been given another $338 million.

“Congress has given us practically a blank check on this construction,” he told the officers, adding as an afterthought, “that makes it all the more incumbent upon all of us to pay close attention to our financial transactions.” In truth, Somervell was little concerned with cost overruns. “We’re buying time, and time is the most expensive commodity in the world,” he told a newspaper columnist. “Time and economy don’t mix.”

That attitude alarmed the junior senator from Missouri, who was beginning to poke into the nation’s enormous defense spending. Somervell was exactly the sort of regular Army officer that Harry S. Truman had resented as a Missouri National Guard captain commanding an artillery battery in France during World War I. Truman considered Somervell a martinet who “cared absolutely nothing about money.” Somervell, Truman once noted with a touch of pride, did not like him “because I stuck pins in him.”

Somervell did despise Truman, considering him a headline-hunting hypocrite. The story Somervell told close associates over the years was that Truman’s enmity toward him, as well as the special Senate committee Truman created to investigate defense spending, resulted from Somervell’s refusal to select a contractor favored by the senator. “They threatened to form the committee to make our lives miserable if we did not give the contract for the St. Louis Small Arms Plant” to Truman’s choice, Somervell later wrote in a letter, and he claimed to have proof of the threat in a safe-deposit box.

The skill Somervell normally used to assuage members of Congress quickly deserted him in his dealings with Truman. Major Gar Davidson, summoned to Somervell’s office one day in early 1941, listened in alarm as the general and the senator went at it over the telephone. “Mr. Senator,” Somervell concluded the conversation, “as far as I’m concerned you can go piss up a rope.” That remark, Davidson believed, “was the straw of insolent independence that broke the camel’s back and precipitated the Truman Committee.”

The committee was established in March 1941, and its first target was Somervell’s construction program. Whether instigated by Somervell’s invective, Truman’s spite, or simply the senator’s dismay at wasteful spending, the committee quickly became a thorn in the general’s side. The committee’s report that summer charged that the Army camp construction program had wasted “several hundred million dollars,” and Truman told the Senate he was “utterly astounded” at evidence of negligence and inefficiency on the part of the War Department.

Truman’s slings and arrows dented Somervell’s armor, but he was hardly vanquished. At the White House and at the top of the War Department, Somervell was seen as a miracle man. Stimson called him a man “who could throw away the book and get results in the face of unexpected handicaps and obstacles.” Truman was correct that there had been terrible budget overruns: The cost of 229 troop facilities, originally estimated at $515 million, came to $828 million. But much of the added cost was due to early, ridiculously low War Department estimates that predated Somervell’s tenure. Under Secretary of War Robert Patterson stoutly defended Somervell against Truman’s attacks, denouncing “the namby-pamby attitude now assumed toward the men who were called for the purpose of creating an army.”

The new Army was housed. Somervell’s next task would be to create a home for the War Department itself.

Who is this stinker?

One man in particular deserved credit for the remarkable turnaround in the Construction Division, in the opinion of Colonel Leslie R. Groves, the paunchy Corps of Engineers officer who served as Somervell’s chief of operations. That would be Groves himself. And it was Groves whom Somervell would rely upon most to build the new War Department headquarters.

Groves was bemused by Somervell’s mania for publicity, calling it a “disease.” Somervell had “tremendous ability, more than anybody I have ever seen in some respects,” Groves later said. But Somervell overlooked one thing in modeling himself after Teddy Roosevelt, in the view of Groves, who keenly studied his superior’s methods. Somervell forgot that Teddy just didn’t build up Teddy; he built up the Rough Riders too.

Leslie Groves was, if anything, even more supremely confident than Somervell. Beneath his thick and graying dark hair—iron gray, he called it—were fine facial features, including a trim mustache and penetrating, unblinking blue eyes that moderated his jowls.

“Ruthless” was the word used to describe Groves almost as often as it was Somervell. The difference, in the view of an officer who knew them both, was that Somervell “was a gentleman as well as a driver.” While Somervell could be quite charming and urbane, Groves biographer Robert S. Norris noted, this was “something rarely said about Groves.” Blunt and brusque, with the grace of a bulldozer, Groves had consistently won high marks from superiors for his engineering and administrative skills, and consistently lower marks for his tact and military bearing.

“When you looked at…Groves,” a fellow engineer officer remembered, “a little alarm bell rang ‘Caution’ in your brain.”

Groves, sent to help the struggling Construction Division months before Somervell’s arrival, had issued a series of stinging critiques. Captain Donald Antes, a normally good-natured construction officer, was so outraged he wanted “to get a shotgun and go looking for someone” after reading one Groves report. “Who is this stinker?” Antes asked.

Hartman had been forced in November 1940 to accept Groves, then a major, as his deputy. The Quartermaster Corps viewed him as a spy for the Corps of Engineers, their historical rival, which they correctly suspected was trying to wrest control of construction. Groves—who adroitly parlayed the new job into a promotion two ranks to colonel—was soon issuing orders to older, more experienced quartermaster officers who seethed at the interloper’s impertinence. But Groves’s competence and coolness were beyond question.

Groves could not walk out of his office without being accosted by frantic construction officers needing immediate decisions on projects around the country. “Usually 4 or 5 other men would keep trailing me to take the place of the man who had first gotten hold of me,” he later said. Groves figured he was making one multimillion-dollar decision for every hundred feet of corridor walked. It was no sweat for Groves. “Once you have made decisions like that you are not scared when you get to the bigger ones,” he said.

Groves, known as Dick to his family, was the son of an Army chaplain who served in posts around the world, from the Philippines to China during the Boxer Rebellion to Fort Apache in Arizona. The boy’s imagination was stirred by the tales he heard from old Indian fighters at the western posts where his father was stationed. His mother’s death when he was sixteen—possibly from ptomaine poisoning—marked the end of a carefree childhood. Fired by a competitive spirit, Dick excelled in school and earned admission to West Point in 1916. At the academy he kept largely to himself, devoting endless hours to study; he earned a reputation as a scold for lecturing other cadets against squandering opportunities. Classmates called him “Greasy” in honor of his thick, oily hair.

Groves’s class graduated from West Point in November 1918, nearly two years early because of the American entry into World War I, but too late to see any action. Ranking fourth in his class, Groves was commissioned a second lieutenant in the Corps of Engineers. Over the next two decades in various assignments, Groves built a solid record of accomplishment and a reputation as an officer who completed projects ahead of schedule.

The Corps of Engineers was a small world, and Groves eventually encountered Somervell, four years his senior. They shared a mentor. Colonel Ernest “Pot” Graves, Somervell’s old commander in Mexico and France and by then a minor deity in the corps, had taken Groves under his wing when the latter was assigned in July 1931 to the Office of the Chief of Engineers in Washington. The gruff and husky Graves, who had been a star lineman and coach for West Point, imparted his football-as-life philosophy during the long walks the two took most mornings from their homes off Connecticut Avenue to their office in the Munitions Building on the Mall. Graves was deaf and Groves had to raise his deep voice to a shout to be heard. No master of the King’s English, Graves would respond in the blunt and taciturn language he had employed as a coach. “It must have been a sight to behold,” Groves’s son recalled many years later. But Groves absorbed Pot’s message: Brains, willpower, and integrity were the core standards by which men were measured.