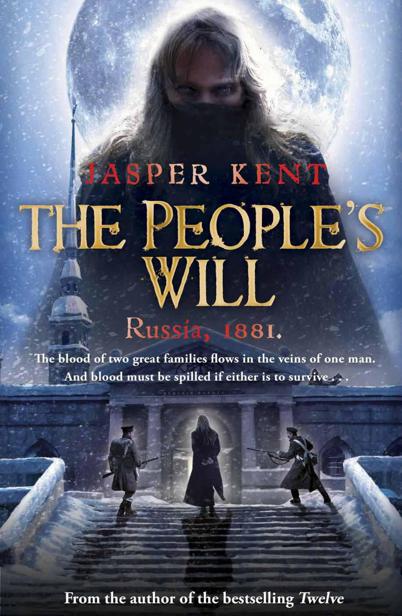

The People's Will

Authors: Jasper Kent

Tags: #Fantasy, #Horror, #Fiction, #Historical, #General

The next moment he was upon him, his eyes blazing, his mouth open to reveal his fangs.

Osokin began to pray, not that he would live but that he would truly die…

Turkmenistan 1881: the fortress city of Geok Tepe has fallen to the Russians.

Beneath its citadel sits a prisoner. He hasn’t moved from his chair for two years. Neither has he felt the sun on his face for more than fifty… although for that he is grateful.

Into this subterranean gaol marches a Russian officer. He has come for the captive. Not to release him, but to return him to St Petersburg – to deliver him into the hands of an old, old enemy who would visit damnation upon the ruling family of Russia: the great vampire Zmyeevich…

But there is another who has escaped Geok Tepe and followed the prisoner. He is not concerned with the fate of the tsar, or Zmyeevich or the officer. All he desires is revenge.

And other forces have a part to play. A group of revolutionaries has vowed to bring the dictatorship of Tsar Aleksandr to an end, and with it the entire Romanov dynasty. They call themselves The People’s Will…

Selected Romanov and Danilov Family Tree

Characters of the Danilov Quintet

Jasper Kent

For M.B.K. and E.B.K.

Measurements

Much of the Russian Imperial measurement system was based by Tsar Peter the Great on the British system. Thus a

diuym

is exactly equal to an inch (the English word is used in the text) and a foot is both the same word and measurement in English and Russian. A

funt

is translated as a pound, though weighs only about nine-tenths of a British pound. A

verst

is a unit of distance slightly greater than a kilometre.

Dates

During the nineteenth century, Russians based their dates on the old Julian Calendar, which in the 1880s was twelve days behind the Gregorian Calendar used in West Europe.

In the text dates are given in the Russian form and so, for example, the death of Dostoyevsky is placed on 28 January 1881, where Western history books have it on 9 February.

With thanks to John Dunne for his knowledge of Saint George’s Church in Esher, Stéphane Marsan for help with the French language and Seçkin Selvi for advice on Ottoman Istanbul.

Reigning tsars and tsaritsas shown in

bold

.

Fictional characters shown in

italic

‘#’ indicates unmarried parentage.

Dates are

birth-[start of reign]-[end of reign]-death

Only the scoundrels have forgotten that strength is with those whose blood flows, not with those who cause blood to be shed. There it is – the law of blood on earth.

Fyodor Dostoyevsky, writing shortly before his death in 1881

The verdict was unanimous. The sentence was death.

In the summer of 1879 the Executive Committee of

Zemlya ee Volya

– Land and Liberty – held a congress in the central Russian town of Lipetsk. There were eleven of them. It required twelve to constitute a jury, but they would be enough. The very idea of a jury was an innovation in Russia – one that had been instigated by the accused himself, a particularly august Russian. They came from all parts of the motherland – from Petersburg and Moscow, of course, but also from the south; from Gelendzhik and Odessa and Kiev. It was those from the south who argued most keenly for a death sentence. They knew poverty better, or had at least witnessed it more closely. None of the Executive Committee was truly poor, though some had parents who had been serfs – until emancipation, eighteen years before. Some might catch a hint of irony that the condemned man was also the emancipator, but sentimentality was a weakness.

He

would not be sentimental when it came to dealing with

them

.

Lipetsk was a spa town and the eleven of them – ten men and one woman – arrived in ones and twos, under the guise of patients. They drank the waters, bathed in the mud and rowed on the lake, gazing into its clear, fishless waters. Shiryaev suggested that the minerals which made the waters so healthy for men meant also that fish could not live in them. Shiryaev was a scientist. That would prove useful.

The lake was known to locals as the Antichrist Pond. It was Frolenko who asked how the name arose. The antichrist in question, so they were told, was none other than Tsar Pyotr I –

Peter the Great. The Executive Committee hid their smiles. Pyotr was the great-great-great-grandfather of the man they had come here to judge. When he had begun to reform Russian society at the beginning of the eighteenth century, many believed him to be the false prophet that the Bible foretold. Today the members of Land and Liberty held Aleksandr II in similar regard, though they cared little for Christian mythology.

On 15 June the Executive Committee made their way to a forest outside the town; though a popular spot for picnics, they managed to find a secluded glade. It was not their main purpose, but they too had brought food, wine and vodka. They were in a merry mood. On the way there Zhelyabov showed off his enormous strength, lifting a passing droshky by its rear axle and stopping the horse in its tracks. They did not mind drawing attention to themselves; no one would guess their true purpose.

After they had eaten, Aleksandr Dmitrievich Mihailov read out the charges against his namesake, Aleksandr Nikolayevich Romanov. The tsar, though not present to face his accusers, had but one defence. Mihailov dismissed it. ‘The emperor has destroyed in the second half of his reign almost all the good he permitted to be done by the progressive figures of the sixties,’ he explained to the others. Each of them was asked in turn whether the reforms of Aleksandr’s earlier reign could win him a pardon for the evils of the present and for those he would yet inflict upon the country if allowed to live. From each came the same answer: ‘No.’

The sentence was passed.

Then they went on to discuss how the execution was to take place and how, once the tsar was dead, the whole edifice of monarchy would be brought down. The second matter seemed simple, almost dull. Revolution would be brought about by the people. On Aleksandr’s death the masses would sense their freedom. It would be more a question of how to guide the transformation of government than how to instigate it. Matters would be helped though if the tsar was not the only one to die. It would be easier if there was no obvious successor. The tsarevich, Aleksandr Aleksandrovich, should not become Aleksandr III. His son, though just eleven, should not become Nikolai II. There were

those who would rally even to a child emperor if he bore the Romanov name.

But the tsar himself must be the prime target. As to how he would die, it was Shiryaev, the scientist, who made the suggestion – a new invention to bring about a new age: dynamite. It provided everything they needed. It would give the executioner the opportunity of escape; it stood the chance of dealing with those around the tsar as well as the tyrant himself; and it would be noticed. Land and Liberty had learned from their French predecessors that terror itself was a political statement.

And so the Congress of Lipetsk closed with much decided. The Executive Committee knew what had to be done. They knew how it was to be done. All that remained was to choose when.

But the decisions of the Executive Committee were not entirely popular among the wider membership of Land and Liberty. A further congress took place in Voronezh and within two months Land and Liberty was no more. Those who disagreed with the conclusions reached in Lipetsk formed their own party, Black Repartition, dedicated to a fairer distribution of land for the peasants, brought about by political means.

The Executive Committee, and many others, remained faithful to what they had decided; remained dedicated to carrying out the sentence which they had passed upon the tsar. They too chose a new name for their group, a name which described in simple terms that which they believed themselves … which they

knew

themselves to embody.

They called themselves

Narodnaya Volya

– the People’s Will.

The verdict was unanimous. The sentence was death.

This trial had been a simpler affair, though it had preceded the events of Lipetsk by over a decade. It had taken place in Saratov in 1865. The accused was not a member of the imperial family, or the nobility, or even a citizen of Russia, though it was in Russia that his offences had been committed. With him there was no need to balance the good of his earlier years with the evils of his later life. There was no mitigation for his crimes.

Where the trial in Lipetsk would be forced to function with only eleven jurors, in Saratov there were just two. Even so, they

followed the procedures of a trial, taking on all the necessary roles between them. For one of the two it was a game, for the other an obsession. It was the older of them, the woman, who spoke most. She was counsel for the prosecution and the chief witness. Other witnesses could not be present, so she represented them, retelling their experiences as best she knew them. She even acted as counsel for the defence. When the judge called on her to present her case she stood up, took a deep breath and then returned to her seat without a word. The judge giggled.

Then the jury – so recently acting as judge and counsel – retired. Unanimity between two was easier than between eleven, but there had never been any doubt as to the verdict. It fell to the judge to announce what they had decided. Some might see it as pointless that the only person he had to announce it to had moments before sat with him on the jury, but he understood the concept of play-acting.

Having discovered the verdict it was the judge’s duty to pass sentence. The counsel for the prosecution made a strong case for death, against which the defence could find no arguments. The judge did not deliberate for long. He spoke the single word ‘Death’ in a whisper. It was an onerous decision for any judge to make, more so because it meant that one day he would have to take on another role – that of executioner.